COVER STORY: 10 milestones that shaped Colorado’s modern political world

It’s been 50 years since Colorado turned the page on the post-War period and plunged into the state’s modern political era as a new generation of leaders took the stage to grapple with challenges confronting the rapidly changing state.

Known as a politically balanced state for most of its history – long before TV newscasters assigned the red, blue and purple color scheme to designate partisan lean – Colorado has stood apart from its neighbors’ enduring traditions of single-party rule while sharing a distinctive streak of Western independence.

Beginning in 1972, when Colorado voters shuffled the state’s congressional delegation – trading in powerful congressional incumbents for politicians more in tune with the electorate’s emerging anti-war and pro-environment sentiments – the state’s political direction has routinely been up for grabs, sometimes lurching from one side to the other between elections.

Over the past five decades, Democratic and Republican candidates have been roughly equally as likely to carry the statewide vote in races for president and senator, though Democrats have dominated gubernatorial elections, winning 10 of the last 12. Until 2004, Republicans held nearly unbroken sway over the General Assembly, keeping state government mostly divided, but have struggled since.

In consultation with political scientists and veteran strategists, we’ve compiled a list of 10 key events that have carved the contours of Colorado’s modern political landscape.

Voters spurn Winter Olympics

In 1972, Colorado did something that had never been done before or since when a wide majority of voters rejected an already-awarded Olympic Games.

Led by an unlikely coalition of budding environmentalists and fiscal hawks, Proposition 8, which effectively blocked Denver’s successful bid to host the 1976 Winter Games, passed with about 60% of the vote.

The unprecedented move propelled the state from the more staid politics of the previous decade and accelerated Colorado’s break from its more conservative Rocky Mountain neighbors. It also crystalized an abiding tension between the state’s appetite for growth and concerns over the environment.

The Citizens for Colorado’s Future campaign thrust one of its young organizers into the political spotlight, turning a Wisconsin transplant who had moved to Colorado a decade earlier in order to be close to the mountains into a rising star statewide.

Denver Democrat Dick Lamm, who had been making a name for himself by driving controversial legislation in the state House, went on to win election as governor two years later after he walked the state. Twice reelected, Lamm would set Colorado’s course for future decades and become its longest-serving governor until his successor, Roy Romer, duplicated the feat before voter-approved term limits kicked in during the late 1990s.

That same year, state voters sent the first woman to Congress with the election of Denver Democrat Pat Schroeder, who would become a prominent national voice during her 12 terms in Washington.

The Olympics rejection itself continues to cast a shadow in Colorado. Decades after voters prohibited spending public funds on Olympic venues – leading the 1976 Winter Games to relocate to Innsbruck, Austria – Denver voters in 2019 established a requirement that any future Olympic bid be subject to a public vote, with 80% of voters effectively putting the brakes on such proposals.

Bill Armstrong elected to the Senate

Still reeling from the Democrats’ Watergate-fueled wins four years earlier, Colorado Republicans regrouped and planted the seeds of their comeback in 1978, when three-term U.S. Rep. Bill Armstrong, an Aurora-based media mogul, unseated Democratic U.S. Sen. Floyd Haskell.

Not only did Armstrong’s win announce the GOP’s return to the statewide winners circle, but it also launched the steadfast conservative onto the national stage, where he quickly defined a new brand of Western Republicanism.

First elected to Congress in 1972 in the newly created 5th Congressional District – encompassing Arapahoe County in the metro area and El Paso County to the south – Armstrong became the de facto leader of Colorado Republicans, both with his command of policy and by example.

More than anyone in the ensuing decades, Armstrong carved out a political persona that set the tone for his fellow Republicans in Colorado, from Hank Brown, who succeeded him in the Senate, to Bill Owens, the last Republican to be elected governor, and to dozens of other prominent GOP politicians who harvested fields first plowed by Armstrong.

Armstrong’s election reset Colorado’s top-level political equation, sending one senator from each major party to represent the state in Washington, D.C. in a pattern that would hold – with only occasional exceptions – for decades.

His win also demonstrated state voters’ propensity to split their tickets, since Armstrong carried the Senate race by about 20 points on the same day Lamm won his second term as governor by about the same margin.

Hart survives challenge from Buchanan

These days, candidates are as likely to petition their way onto the ballot as they are to go through the caucus and assembly process, but it was nearly unheard-of for major politicians to take the petition route in 1980. That’s when Republican Mary Estill Buchanan, the incumbent secretary of state, not only qualified for the U.S. Senate primary by petition but won the nomination by a whisker and nearly unseated Democratic U.S. Sen. Gary Hart in a down-to-the-wire race.

Hart, the Denver attorney who had denied Republican U.S. Sen. Peter Dominick a third term in 1974, was facing political headwinds as he sought a second term on the same ticket as then-President Jimmy Carter, drawing a crowded field of potential challengers. Among them was Buchanan, the lone statewide Republican elected official to survive voters’ post-Watergate wrath in 1974, along with six men with diverse backgrounds. Already at odds with GOP leaders for her liberal positions on the Equal Rights Amendment and gay rights, Buchanan failed to make the ballot at a turbulent state assembly, finishing in a surprise fifth place.

She drew fierce criticism from party bosses when she declared her intent to gather signatures, including denunciation from the state GOP chairman, who called Buchanan’s move “harmful … to party unity” and said she was refusing “to recognize her sound defeat at the convention.” Buchanan forged ahead but, even after submitting her signatures, faced a court challenge from a leading county GOP chairman. When she survived in court and made the primary ballot, she was greeted with a front-page headline that blared, “Give ‘Em Hell, Mary.”

Buchanan prevailed in the four-way primary, winning by 1 point over former Georgia Congressman Howard “Bo” Callaway, who served as secretary of the Army in the Nixon administration.

Two short months later – Colorado’s primary used to be held in early September – Buchanan came within 1.6 points of beating Hart, who would later cement his place in the political firmament as the Colorado Democrat who has so far come closest to the White House. Hart finished second behind former Vice President Walter Mondale in the 1984 presidential primaries and entered the 1988 race as the undisputed frontrunner, until his campaign was derailed by salacious rumors involving an alleged affair with a Miami model.

While internal GOP strife continued through the 1980 general election – including an incident just days before Election Day, when Buchanan suspected hard-core conservatives dissuaded Reagan from endorsing her, potentially costing her a win – Buchanan stands as the first Colorado woman nominated by either major party for the two top statewide offices, senator and governor. More than 40 years later, Buchanan has some company in the nominees circle – Senate nominees Nancy Dick, Josie Heath and Dottie Lamm and gubernatorial nominee Gail Schoettler, all Democrats – but neither office has yet been held by a woman.

Reinforcing the Colorado electorate’s reputation for ticket-splitting, Hart barely won a ticket back to D.C. at the same time state voters swung hard for Reagan, giving the Republican a 20-point victory.

Voters approve Amendment 2, TABOR

The same night in 1992 that Colorado handed its electoral votes to Democrat Bill Clinton – favoring a Democratic presidential nominee for the first time since the 1964 LBJ landslide – voters OK’d two amendments to the state constitution that have exerted a strong influence on Colorado politics across the decades, even though one of them never went into effect.

Championed by a Colorado Springs car dealer and the evangelical Christian organization he led, Colorado For Family Values, Amendment 2 made it illegal for any government in the state to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. Sold as a ban on “special rights” for LGBTQ Coloradans, the measure spurred an immediate national backlash, prompting widespread boycotts and a nickname, “the Hate State,” that lingered for years.

Voters also approved the Taxpayer Bill of Rights, a complex measure authored by Colorado Springs anti-tax advocate Douglas Bruce that sets limits on government spending and requires voter approval for higher taxes, among other provisions.

Clinton won with a 40% plurality in a three-way race against incumbent Republican President George H.W. Bush and Texas billionaire Ross Perot, but the two amendments passed with clear majorities – TABOR with 54% of the vote and Amendment 2 with 53%.

Within two years, the Colorado Supreme Court had struck down Amendment 2, and in May 1996 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the landmark Romer v. Evans decision that the measure violated the 14th Amendment. Writing for the 6-3 majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy summarized the court’s reasoning: “A state cannot so deem a class of persons a stranger to its laws.”

In the meantime, its passage energized an emerging gay-rights community, which formed high-profile advocacy groups – including Ground Zero in Colorado Springs, a reminder of Amendment 2’s origin – and spurred a generation of LGBTQ Coloradans and their allies to plunge into politics.

TABOR, on the other hand, has exerted a powerful influence on Colorado at all levels and remains one of the more polarizing aspects of the state government. Though reactions don’t fall exclusively on party lines, Republicans tend to venerate the measure and celebrate the unique power Colorado voters have to vote on tax hikes, while Democrats typically lay many of the state’s problems at its feet even as they develop work-arounds and challenge elements of the amendment in court.

The split was evident on election night, when Bruce maintained that taxpayers wouldn’t feel any pain, while opponents – led by labor, education, law enforcement and tourism groups – warned that local services would soon face drastic cuts. Love it or hate it, decades later TABOR is as much a part of Colorado’s political atmosphere as anything.

Democrats’ ‘Gang of Four’ devises The Blueprint

Among the Coloradans motivated to political involvement by Amendment 2 was software magnate Tim Gill, founder of Quark Inc., a pioneering, Denver-based desktop-publishing software company. Soon after the amendment passed, he created the nonprofit Gill Foundation to fund philanthropic endeavors while raising awareness about the state’s LGBTQ residents. Gill also got serious about using some of his vast resources to advocate for what he called equal liberties regardless of one’s sexual orientation.

“Nothing can compare to the psychological trauma of realizing that more than half the people in your state believe that you don’t deserve equal rights,” Gill said later in an interview.

In concert with three other wealthy Coloradans – medical equipment heir Pat Stryker, tech entrepreneur Jared Polis and petroleum geologist Rutt Bridges – Gill transformed political fundraising and organizing in Colorado in the run-up to the 2004 election. In a strategy later chronicled in numerous articles and the 2010 book, “The Blueprint: How the Democrats Won Colorado (and Why Republicans Everywhere Should Care),” by Colorado authors Adam Schrager and Rob Witwer, the group – dubbed the “Gang of Four” – created and helped fund a new kind of political machine dedicated to electing Democrats.

On the day after the 2004 election, Colorado woke up to a dramatically altered political landscape, including Democratic Attorney General Ken Salazar’s election to the U.S. Senate that had been held by a Republican for 10 years and his brother John Salazar’s election to a U.S. House seat that had been in GOP hands for a dozen years. In the election’s most stunning result, however, Democrats had won majorities in both chambers of the General Assembly for the first time since the early 1960s.

It only emerged later the role played behind the scenes by Gill, Stryker, Bridges and Polis, who had won election four years earlier to the State Board of Education after outspending the Republican incumbent by 100-to-1. (Polis won election to Congress in 2008 and in 2018 was elected governor, becoming the first openly gay candidate to win the office anywhere in the country.)

Colorado Republicans have tried to match the multi-pronged political infrastructure initially funded by the wealthy group, even scoring occasional wins, but the approach developed by the Gang of Four endures.

Obama accepts nomination in Denver

It’s hard to convey how quickly Colorado’s political winds shifted after the Democrats upended the order in 2004. Within two years, the party had retaken the governor’s office and national Democrats had picked Denver as the host city for the 2008 Democratic National Convention, which would put the city at the center of the political universe and cement the state’s status as a battleground.

All eyes were on Colorado when the Democrats nominated Illinois Sen. Barack Obama and his running mate, Delaware Sen. Joe Biden, capped by Obama’s acceptance speech at Invesco Field at Mile High, which drew tens of thousands of Coloradans to what was as much a campaign organizing event as it was a made-for-TV spectacle.

After filling Denver’s Civic Center in late October with a crowd estimated at nearly 150,000 people – holding the record for the largest political rally in Colorado history – Obama carried the state over GOP nominee John McCain by about 9 points, marking only the second time a Democrat had won Colorado’s electoral votes in more than four decades. For the first time, Colorado was the “tipping point” state – the state whose electoral votes put the winning presidential candidate over the required 270 Electoral College majority. (Colorado would fill the same role in 2012, when Obama won Colorado by about 5 points over Republican nominee Mitt Romney.)

Colorado Democrats nearly ran the table that year, too, including flipping an open, Republican-held Senate seat with Democratic Mark Udall’s win over GOP nominee Bob Schaffer after Republican U.S. Sen. Wayne Allard announced he wouldn’t seek a third term. When the dust settled, Democrats held both Senate seats, five of the state’s seven U.S. House seats, all but one of the statewide executive offices, and both chambers of the legislature – an exact mirror image of the Republicans’ dominance just six years earlier, following the 2002 election.

Dan Maes wins GOP primary for governor

In the first Obama midterm election, Colorado Republicans regained ground across the state but were stymied in their attempts to win the top prizes on the statewide ballot in 2010 – governor and senator – by the rise of the Tea Party and a series of scandals and missteps that curbed the GOP’s momentum.

After Gov. Bill Ritter, the incumbent Democrat, announced he wouldn’t seek a second term, Denver Mayor John Hickenlooper joined the race in an election year already dominated by voters’ impatience with the slow recovery from the 2008 financial meltdown.

Undermined by late-breaking plagiarism allegations, the Republicans’ gubernatorial frontrunner, former U.S. Rep. Scott McInnis, lost the primary to political newcomer Dan Maes, an Evergreen businessman. Maes promptly plunged the state GOP into turmoil amid a steady drip of gaffes, questionable revelations about his background and a headline-grabbing campaign finance violation.

Droves of Republican officials and politicians distanced themselves from Maes, who rebuffed efforts to force him out of the race. That’s when former Republican U.S. Rep. Tom Tancredo switched his registration to a previously obscure third party and mounted a run for governor that came close to exiling Colorado Republicans to minor-party status.

Hickenlooper, who launched his run with a famous TV ad renouncing negative campaign ads, mostly let state Republicans battle it out among themselves and cruised to a comfortable win with 51% of the vote. Tancredo finished with a strong 36% – the best performance by a third-party candidate in Colorado since the early years of the last century – with Maes bringing up the rear at just over 11%, narrowly escaping the sub-10% finish that would have cost the GOP its designation as one of the state’s two major political parties.

In the same election, Hickenlooper’s former chief of staff, Democrat Michael Bennet, held on to the U.S. Senate seat he’d won by appointment two years earlier after Salazar resigned to join the Obama cabinet as interior secretary. Bennet squeaked past Republican nominee Ken Buck, a prosecutor and Tea Party favorite, who likely torpedoed his chances in a national debate weeks before the election with an off-the-cuff remark comparing homosexuality to alcoholism.

Elsewhere on the ballot, Colorado Republicans romped, unseating two Democratic congressional incumbents, sweeping the statewide executive offices below governor and winning the majority in the state House.

With the exception of Maes, who quickly disappeared from public view, the main players in the 2010 election continue to dominate Colorado’s political scene a dozen years later. Bennet and Hickenlooper represent Colorado in the Senate, and both ran long-shot campaigns for the presidency two years ago. Bennet is seeking a third term this year. Tancredo rejoined the Republican Party before making two more unsuccessful runs for governor, while Buck is running for his fifth term in the U.S. House and spent two years as state GOP chairman.

Cory Gardner elected to the Senate

If not for Cory Gardner’s election to the U.S. Senate in 2014, Colorado Republicans would be approaching the tail end of a generation-long drought in Colorado, rather than the still-vexing, nearly eight-year span since the party has won a top-ticket race in the state.

The preternaturally cheerful politician from Yuma – a national magazine writer once compared him to a “human ray of sunshine” crossed with an “over-caffeinated hamster” – remains the only GOP candidate for senator or governor to carry Colorado since 2002, when Bill Owens won reelection as governor and Allard won his second Senate term. It’s been almost as long since the GOP presidential nominee won the state’s electoral votes, something last accomplished by George W. Bush in 2004.

Gardner lost his bid for a second term in the last cycle, but the similarities between this year’s election and Gardner’s 2014 win over Udall – the last time a Democrat occupied the White House during a midterm election – have set state Republicans’ pulses racing.

Gardner’s willingness to discard previous positions and then adamantly deny any inconsistency set the tone for a more aggressive brand of politics that spread across the spectrum. The Republican won enough support from suburban, unaffiliated women – the state’s perennial swing bloc – in part by mocking the Udall campaign’s focus on Gardner’s alleged threat to abortion rights. Advocates on both sides of the issue are again sounding the alarm this election year as a reconfigured U.S. Supreme Court – installed with Gardner’s assent – appears poised to overturn 1973’s Roe v. Wade decision.

In yet another example of the state’s penchant for ticket-splitting, Gardner eked out a win at the same time voters handed Hickenlooper a second term by a slightly wider margin. Colorado voters were no longer delivering landslide wins to top-ticket candidates from both parties – like they had when Lamm and Armstrong both carried the state by about 20 points the same year – but appeared to still have a swingy middle.

Ballot measure opens primaries to unaffiliated voters

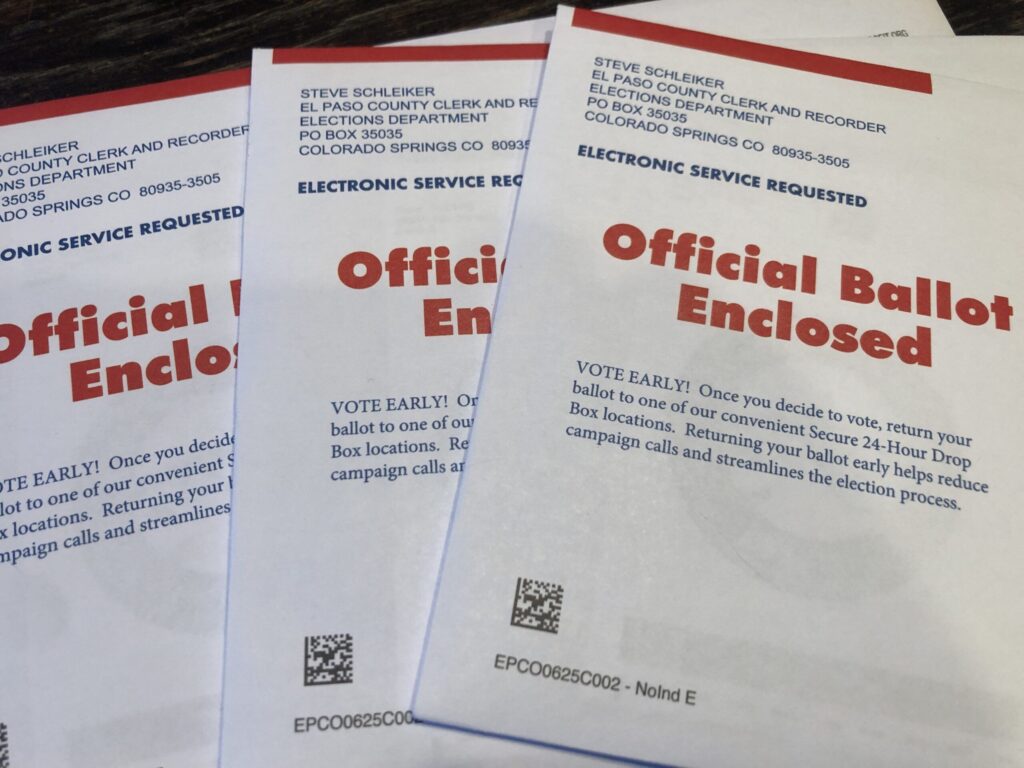

Colorado voters approved a pair of ballot initiatives in 2016 that would change how the state conducts primary elections, with Proposition 107 establishing presidential primaries and Proposition 108 permitting unaffiliated voters to cast ballots in either of the two major parties’ primaries.

The former made sure that Colorado was a frequent stop on the road to the White House in 2020, but it was the latter that appears to have already made a lasting impact on the state’s political dynamics.

Under the new, semi-open primary system, which took effect with the 2018 election, unaffiliated voters who do not request a specific party’s ballot receive both a Republican and Democratic primary ballot in the mail but can only return one of them. (A truly open primary, like exists in some states, would allow Republican and Democratic voters to cast ballots in each other’s primaries.) Supporters of the change argued that since all taxpayers pay for holding the parties’ primary elections, those who aren’t affiliated should have a chance to participate. Some also argued that the influx of unaffiliated voters would help moderate the two parties’ nominees.

While Colorado’s electorate was nearly evenly split between Republicans, Democrats and unaffiliated voters a decade ago, in recent years the share of voters who don’t belong to either major party has soared. According to the latest figures, 44% of Colorado’s active voters are unaffiliated, followed by Democrats at 28.5% and Republicans at 25.5%, with the remainder belonging to minor parties.

Far from making up an undecided middle, polls and ballot returns so far show that the state’s unaffiliated voters lean solidly to the left. This year, twice as many have requested Democratic primary ballots as have said they want GOP ballots, though voters aren’t required to register a preference, so it’s a relatively small sample.

A group of Republicans are so incensed by the situation, however, that they’re suing to overturn the proposition, claiming that allowing unaffiliated voters to help pick their nominees amounts to a violation of their First Amendment right to freedom of assembly, among other complaints.

State Democrats are sure to battle the attempt in court, but they aren’t shy about celebrating the fact that the lawsuit – and a similar attempt last year to cancel the state GOP’s primary altogether – suggests that Republicans don’t want any input from the state’s largest group of voters, which could make those voters less likely to vote for Republicans in November.

Democrats sweep races statewide

Colorado Democrats scored historic wins in 2018 as state voters registered their disapproval of Republicans in former President Donald Trump’s midterm election. In the process, voters handed Democrats complete control of state government for the first time since the 1930s, electing Polis as governor and filling the other statewide constitutional positions – attorney general, secretary of state and state treasurer – with Democrats, while also returning Democrats to the majority in the state Senate and expanding the party’s majority in the state House.

The same night, first-time candidate Jason Crow did something no Democrat had been able to do in three decades when the attorney and Army Special Forces veteran defeated Republican U.S. Rep. Mike Coffman, long considered one of the state GOP’s stalwarts. Democrats also flipped offices in counties that had long been considered Republican strongholds, including Arapahoe and Jefferson counties.

Nothing has done more to shape the contours of Colorado’s recent political landscape than Trump’s 2016 election to the presidency, Republican strategists say, arguing that the Democrats’ 2018 sweep was as much a repudiation of Trump as it was a carte-blanch endorsement of the Democrats.

Still, the Democrats’ sweep was so staggering that longtime observers have been left wondering if the perennial battleground state has slipped entirely into the blue column, a conclusion bolstered by the party’s statewide wins in 2020. With Democrat Joe Biden in the White House, however, Democrats might hold all the reins in Colorado, but they could also bear all the blame as restless voters head to the polls this fall amid a shaky economy, rising crime rates and war in Europe.

Democrats are banking that the electorate has changed enough in recent years to help the party’s chances of keeping Republican gains to a minimum, but state Republicans see opportunity in Biden’s tumbling approval ratings and are confident they’ll be able to prove – for a while at least – that Colorado is still the swing state it’s been over much of the last 50 years.