Report: Colorado’s federal trial court sees time to trial tick up, magistrate judge consent remain low

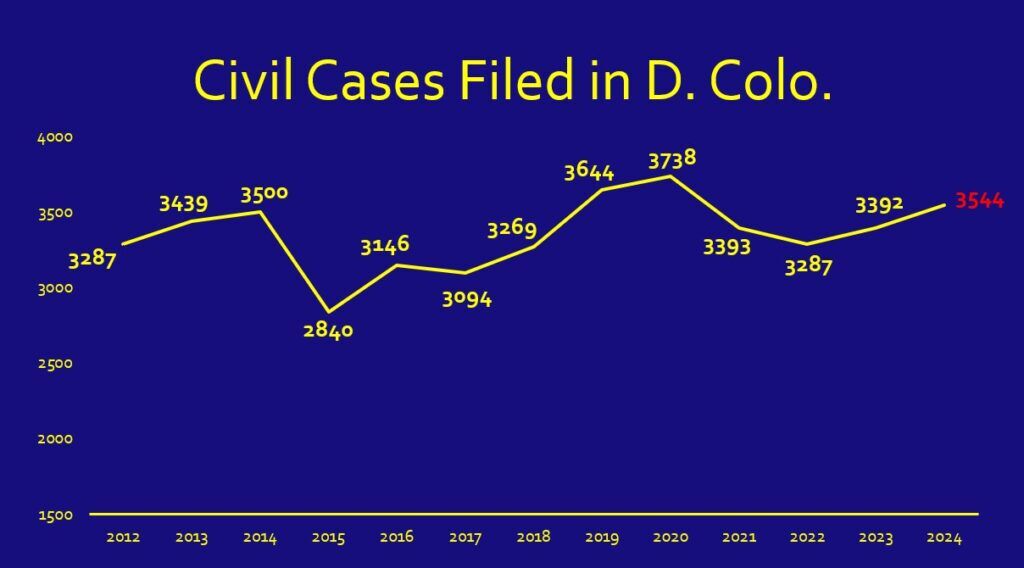

Colorado’s federal trial court saw a slight uptick in the number of civil cases filed in 2024 and also a slight increase in the average time for a case to reach trial, according to a statistical report compiled by U.S. Magistrate Judge N. Reid Neureiter.

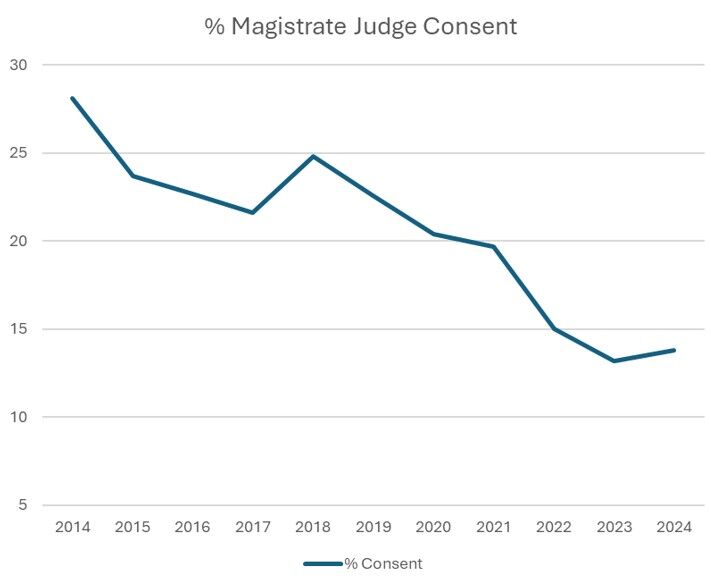

Neureiter also noted the percentage of cases handled exclusively by magistrate judges, as opposed to the presidentially appointed district judges, remains low.

“I hypothesized reasons why,” Neureiter told Colorado Politics. “But the answer is I don’t know. And nobody knows why.”

Previously, then-U.S. Magistrate Judge Michael E. Hegarty provided an annual statistical report to lawyers and judges who work in Colorado’s U.S. District Court. Neureiter took over the presentation after Hegarty’s retirement in January. This year, Neureiter received assistance from intern Charlotte Renner and from a clerk’s office employee, Leigh Roberson, on the report.

The number of civil cases filed in 2024 was 3,544, a 4% increase from the prior year. Meanwhile, cases filed by self-represented, or “pro se,” plaintiffs increased by 15%, to nearly one-third of the civil docket.

There were a total of 31 jury trials and seven bench trials for civil cases. On average, a civil case took 39 months from filing to trial, the longest duration on record since 2012. Civil rights and employment disputes were the most frequently filed types of cases, closely followed by litigation from incarcerated plaintiffs.

Meanwhile, the number of felony criminal cases filed in Colorado decreased from 309 in 2023 to 286 last year. There were a total of 21 criminal trials, all but three of which occurred before a jury. The government secured convictions in 94% of felony cases, a rate in line with the historical average but a large increase from the 55% conviction rate in 2022.

Neureiter’s report found that the rate at which magistrate judges are hearing civil cases remains under 14%. Although district judges, who are nominated by the president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate, can hear cases on their own without the consent of the litigants, magistrate judges who are hired by the court must obtain consent to preside over all aspects of a civil case. Otherwise, their work largely consists of procedural and administrative duties.

Consent occurred 28% of the time in 2014, but a decade later the rate was less than half that.

“Some of the reasons might be that we’ve had turnover in the magistrate judge ranks and we have a number of new ones,” said Neureiter. However, that would not explain why the rate went down last year for the two most senior magistrate judges, Hegarty and Scott T. Varholak.

“Others have hypothesized that there’s been a turnover in the (district judge) ranks and people are more comfortable” with those judges, Neureiter said. Five of the seven active district judges joined the court in 2021 or later.

Last year, there were 154 settlement conferences, which are conducted by magistrate judges in civil cases. Litigation was fully resolved after 72% of the conferences. Hegarty alone accounted for almost half of the days dedicated to settlement negotiations. Neureiter predicted that in 2025, there would be 20% fewer settlement conferences.

Neureiter also looked at motions for dismissal and for summary judgment, both of which can end a civil case without a trial. The average time for judges to issue decisions was six months for both, he found. More than half of the time, such motions were denied in whole or in part.

Finally, Neureiter noted that one district judge has stepped away from the court. Christine M. Arguello, who was appointed in 2008, has stopped taking new cases and her active cases have been reassigned. In 2022, she transitioned to a form of semi-retirement known as “senior status,” while maintaining a reduced caseload.