Federal Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton reflects on Colorado River progress, difficult conversations ahead

What a year it’s been for the seven states of the Colorado River basin.

It began when Camille Touton, commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, told a U.S. Senate committee she would seek reductions of as many as four million acre-feet from those seven states, in order to shore up the nation’s two largest reservoirs and their ability to generate hydropower.

But ultimately, the bureau was willing to accept a three million acre-foot reduction from the three lower basin states, instead of the larger ask from a year ago.

In a Thursday interview with Colorado Politics, Touton said the smaller-than-expected cuts to Colorado River use came down to the state of hydrology from last year to this year, with a wetter winter that she called an “unexpected gift.”

But there’s also the reality of the situation, she said. Most of those reductions will be “front-loaded” by the end of 2024, but what it does is give time for conversations about the future, including the 2026 negotiations around basin operations.

The bureau, along with the lower basin states, will be carefully watching how this round of reductions performs and protects the system, Touton said, in response to a question about further reductions before 2026.

She also noted that what has been accomplished in the past year was difficult, but the dialogue happening in the basin states, including the tribes, shows everyone is committed to the same thing. “Will these conversations get harder? Yes, but I have confidence in our relationships that we will all move forward in a shared direction.”

“That really determines, depending on hydrology and how [those reductions] perform, what we look at moving forward in operations. The lower basin states are confident (the reductions) will perform well and will help protect critical levels,” she said.

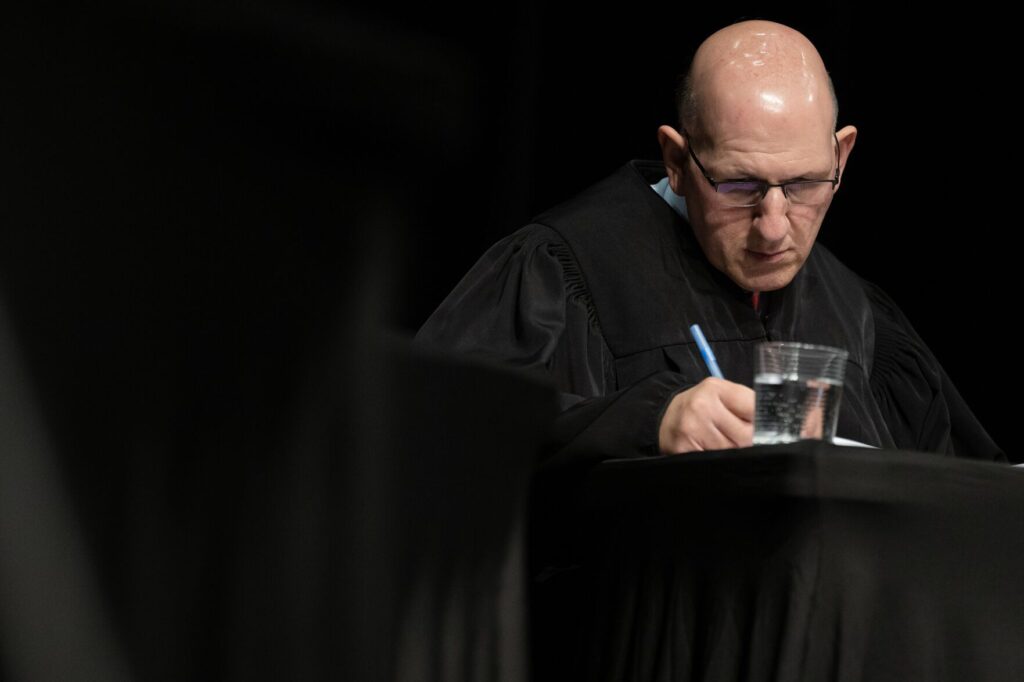

The interview came after Touton on Thursday reflected on the previous year, what has been accomplished and what the future holds for sustainability on the river. Her remarks came at a conference on the “Crisis on the Colorado River.” The conference is an annual event hosted by the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy and the Environment at the University of Colorado Law School.

In the past year, the bureau, the seven states, the 30 American Indian tribes and Mexico have charted a new trajectory for the river, Touton said.

Risks to the system at that time Touton briefed Congress included the plausibility that Lake Powell could drop to an elevation of 3,490 feet by July 2023. That’s the minimum level for power generation, she noted.

Every day since then, the bureau has worked with its partners to develop strategies designed to protect the system, as well as to start the discussions on new operational guidelines to replace the interim guidelines from 2007. The interim guidelines are set to expire in 2026.

Conversations with the partners continued through summer 2022. But by August, the bureau took the first-ever step of declaring a Tier 2A shortage, which meant substantial reductions for Arizona, smaller reductions for Nevada and none for California, holder of the most senior water rights.

In the past year there has been movement on many fronts, Touton said, including federal investments through the Inflation Reduction Act. That provided $4.5 billion for the bureau, most of it directed for drought mitigation, with the Colorado River basin as a priority.

Since last summer, every sector has stepped up on conservation, but Touton pointed out the first offer was from a tribal nation. The Gila River Indian Community of Arizona announced last October it would conserve 750,000 acre-feet over three years in order to help prop up Lake Mead. That showed how critical the tribal partnerships are to the overall effort, Touton explained.

In April, the tribe was awarded $83 million for a major water pipeline project that will put another 20,000 acre-feet into system conservation.

The second tranche of federal money came from the bipartisan Infrastructure Act. The bill devotes $8.3 billion over five years for a variety of water needs, including infrastructure projects, storage, conveyance, desalination and dam safety.

Much of that will head to the Colorado River basin states, she said, and that could yield hundreds of thousands of acre-feet of water in savings.

As to the wet winter and above-average runoff, Touton shared the pessimism of others.

“There are no guarantees that this is more than a one-off,” she said.

In spite of these efforts, Touton said the path forward remains challenging.

Thanks to a recent agreement among the lower basin states to conserve three million acre-feet through 2026, the bureau has temporarily suspended work on a supplemental environmental impact statement (SEIS) that would have put the federal agency in the driver’s seat on water reductions to protect Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

The lower basin agreement will require the three states to put 2.3 million acre-feet into Lake Mead. That effort will be supplement with more than $1 billion in federal dollars from the Inflation Reduction Act that will pay water users to conserve, with the rest coming from voluntary, uncompensated reductions.

“This will give us space and flexibility to move into planning for 2026,” Touton added.

That process is moving quickly. Next week, the Department of the Interior will announce a notice of intent to develop the guidelines for 2026, along with a new draft environmental impact statement that should be ready by late 2024.

In addition, the bureau is now taking a look at evaporation and transmission loss, a long-time bone of contention between the upper basin states and the lower basin states. The upper basin states have taken evaporative loss into consideration with water allocation for more than 40 years, while the lower basin states, who lose about 1 million acre-feet per year from evaporation and transmission, have never accounted for those losses in their allocations.

These actions and investments “speak to the urgency” from the bureau and the Department of the Interior and its efforts to promote collaborative solutions in the basin, Touton said.

“I’d like to ask you to stay the course with us to achieve a sustainable river system,” she said.

Colorado U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper, appearing via Zoom, also spoke of the projects that will come out of the federal funding measures, as well as a water caucus he formed a year ago to generate conversation and awareness among the senators who represent the basin states.

The caucus is not intended to make or influence decisions, Hickenlooper said, but to “turn down the temperature behind closed doors and to be facilitators,” he said.

None of the senators want to meddle in state efforts to come to an agreement, but will provide oversight through the two federal funding measures and make sure that money is spent wisely, he added.

Getting everyone to the table, similar to the process used to develop the Colorado water plan, “is a huge first step … A lot of traditional landscapes and lifestyles are depending on us finding the right solution.”

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com