Advocates diametrically disagree on imprisonment’s role in response to fentanyl crisis

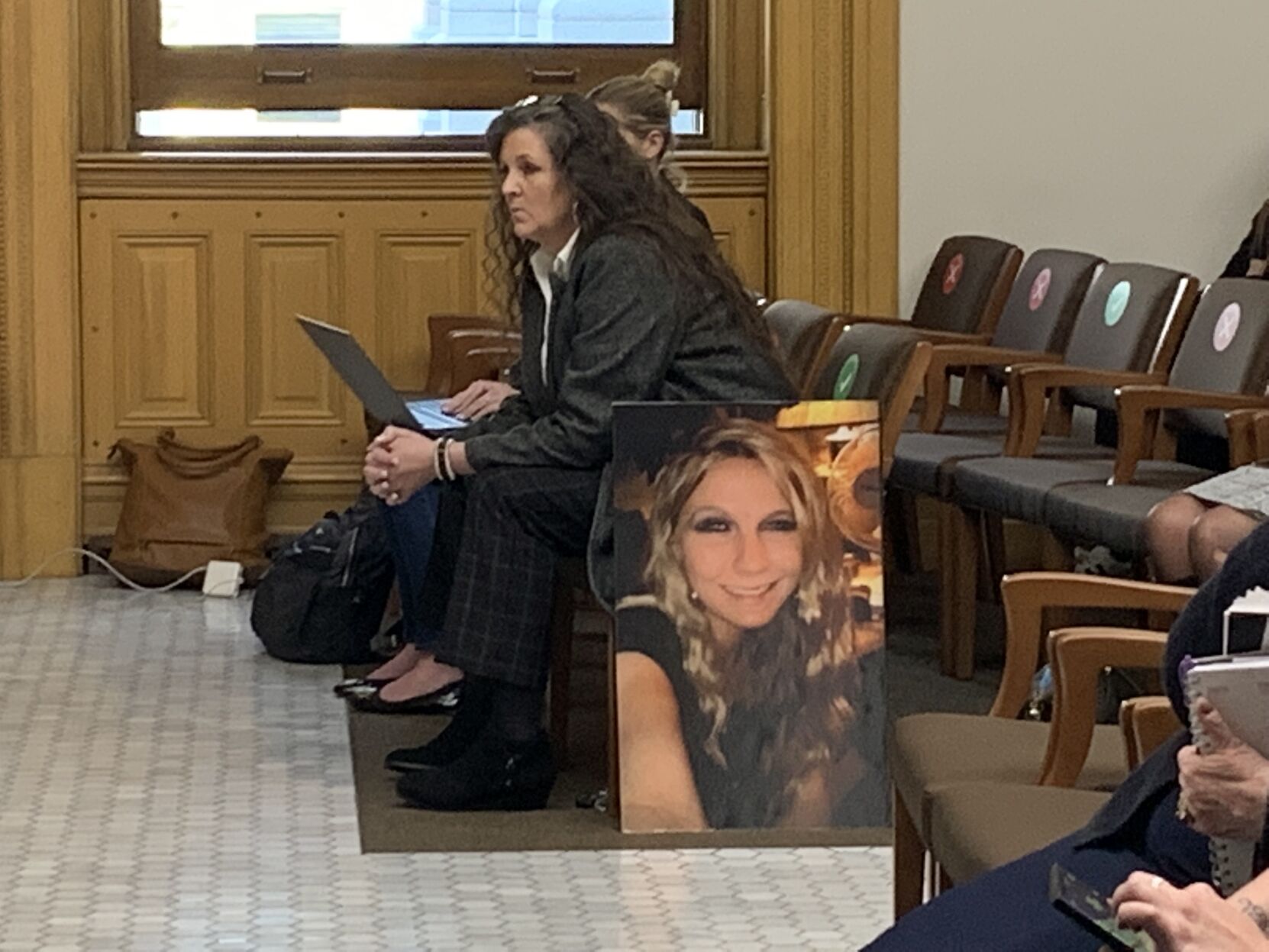

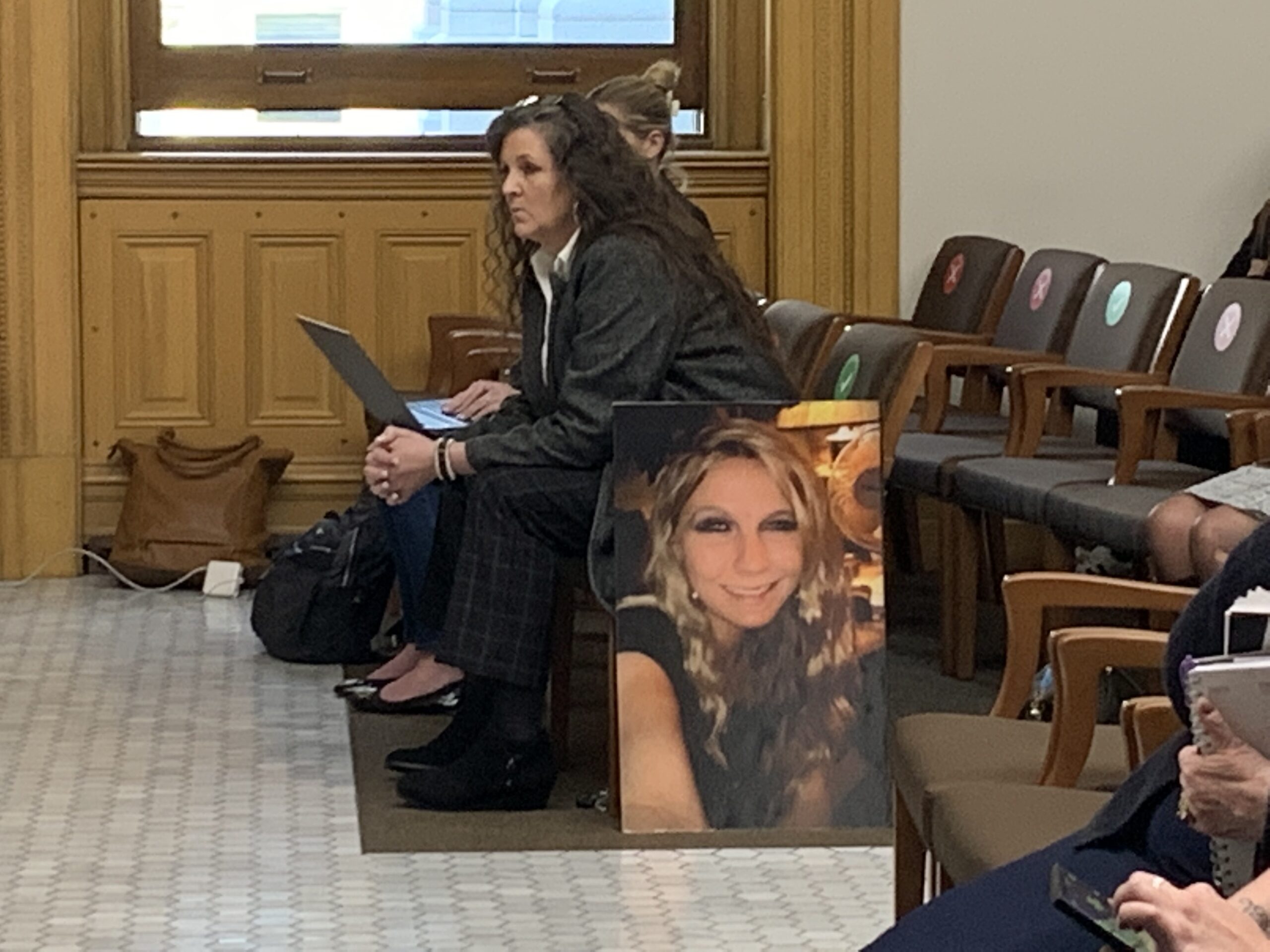

Fighting through tears, Jessica Chavez recounted before a panel of Colorado lawmakers how her daughter, Yesenia, fatally overdosed in July after taking a fentanyl pill she thought was Percocet.

Before her death, Yesi, as her friends called her, had texted her family’s pastor, Chavez told lawmakers. The 21-year-old told him that she wanted “to do more for God.” The pastor told her to come by the church on Saturday, just a few days away.

Yesi died that Thursday. Three months before, her boyfriend had fatally overdosed in his childhood bedroom.

“That was the last text,” Chavez said. “That Saturday never came for her.”

Chavez was among several parents who testified before lawmakers Tuesday about losing their children to fentanyl. They joined an array of experts, law enforcement and health officials who took turns in offering strategies but often battling Tuesday over the legislature’s response to surging fentanyl overdoses. The hours-long hearing revealed the deep policy disagreements among many on the front lines of the spiraling crisis.

The meeting was the first public discussion on the legislature’s sweeping fentanyl legislation, House Bill 1326, which combines tightening of criminal penalties for distributing fentanyl with harm-reduction efforts. Though they broadly agree about the severity of the crisis and need for a robust response, officials on the public health and criminal justice sides repeatedly squared off over questions about the role of criminal penalties and incarceration in confronting the challenge.

Lawmakers worked until nearly 3 a.m. Wednesday morning on the bill, but delayed action on proposed amendments and a final vote until 1:30 p.m. Wednesday.

The debate comes against a backdrop of surging fentanyl overdoses, both in Colorado and nationwide. Nearly 900 Coloradans fatally overdosed after ingesting fentanyl in 2021, a number that’s quadrupled since 2019. Though Colorado’s fatal overdose rate for synthetic drugs, of which fentanyl is the most prevalent, is below the national average, the state’s rate has grown faster than nearly any other state since 2018.

Many in law enforcement – from Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen to Attorney General Phil Weiser – have maintained the proposed legislation doesn’t go far enough and that it should make possession of any amount of pure fentanyl a felony. Currently, possessing 4 grams or fewer is a misdemeanor, a change the legislature made in 2019, when lawmakers passed a bipartisan measure to de-felonize some drug possession.

Harm reduction and health experts, including several physicians who spoke Tuesday, sharply criticized the tougher criminal penalties already in the bill, let alone efforts to toughen criminal sanctions.

Those diametrically opposed positions, expressed in press conferences and public statements since the bill was first unveiled last month, were on full display Tuesday.

Speaker Alec Garnett, the bill’s co-sponsor, opened the hearing by urging the public not to lose sight of the bill’s grand aim because of disagreements over when, how or to what degree low levels of possession should be a felony. But that disagreement overshadowed much of the hearing.

Three Denver physicians, all of whom work with people who use illicit substances, testified that no evidence exists indicating that incarceration and mandatory treatment work to slow drug use and overdoses. They argued that the public health measures in the bill, including more money for Naloxone and fentanyl test strips, don’t outweigh the damage they said tougher penalties, if adopted, would do.

They argued that the proposal would send more people to prison and lead to more fatal overdoses, not fewer.

Research has consistently shown that people with opioid-use disorders are 40 times more likely to fatally overdose shortly after leaving incarceration than the rest of the population. Others noted that people with felony convictions have a harder time securing employment and housing, stresses that further complicate efforts at sobriety.

“There’s robust data to show these types of supply-side interventions do nothing to decrease drug use,” said Sarah Axelrath, a physician who works with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless. “Arresting people who are distributing and focusing on other supply side to substance-use disorders does not reduce drug use and does not stop new people from initiating drug use.”

Josh Barocas of the CU Medical School said criminalization “doesn’t work” and that “the best scientific evidence doesn’t support it.”

As he spoke, a man in the audience interrupted him.

“No one wants fentanyl, you f***ing idiot,” the man shouted.

Lisa Raville, one of Colorado’s most vocal and active harm reduction experts, said if treating drug use as a criminal justice matter worked, “we would’ve gotten this under control a long time ago.” She advocated for safe-use sites – meaning places where users can take illicit substances under the watchful eye of providers – and a state-controlled supply of pharmaceutical-grade drugs, rather than the deadly supply of illicit fentanyl flooding the drug market.

But law enforcement and several district attorneys said that fentanyl is so strong – 2 milligrams is considered a potentially lethal dose – that no amount is safe. Any state response, they argued, should match the severity of the crisis and confront the deadliness of the drug. They also said incarceration can be an impetus for users to get clean and begin the road to recovery.

Deputy Chief Adrian Vasquez of the Colorado Springs Police Department told the committee that any possession of fentanyl should be a felony, that there is no “relatively safe amount of fentanyl” and public policy should demonstrate its seriousness.

District attorneys from Adams, El Paso and Arapahoe counties, for example, asked for an amendment to make mandatory any sentence for someone who deals fentanyl resulting in death. The bill, as introduced, states that charge would not result in a mandatory minimum sentence.

George Brauchler, a former district attorney for the 18th Judicial District, denied that a tougher charge for low-level possession is an attempt to “felonize” addicts. No one goes to prison for simple possession, he insisted. If lawmakers are concerned with whether jails would fill up with addicts, Brauchler suggested putting a sunset on the bill and review its effects in two years.

“Let’s see if we fill up a single prison bed with one addict,” he said.

In response to a question from Rep. Leslie Herod, a Denver Democrat, district attorneys from Boulder and Mesa counties said they do not see criminal cases that involve pure fentanyl.

District Attorney Dan Rubinstein of Mesa County said pure fentanyl is so potent that it’s completely useless to have around and its only intended use is for mixing with other drugs. He also noted that the Colorado Bureau of Investigation is unable to test the purity or level of fentanyl in a pill.

Weaved between the testimony of experts and advocates were those families and friends left behind by loved ones who’d fatally overdosed.

“Me and my peers are scared and don’t know what to do or who to turn to,” said Bo Gribbon, a resident of Denver who said he has lost six friends to fentanyl. He advocated for harsher penalties, particularly for dealers.

Rep. Adrienne Benavidez, D-Commerce City, asked if education about what’s in the drug would make a difference.

Yes, Gribbon said, before adding that most people know that what they’re taking contains fentanyl.

The drug is often pressed into pills that resemble legitimate oxycodone pills, and it’s also increasingly being mixed into other drugs, from methamphetamine and heroin to cocaine, pills that resemble Xanax and even black market marijuana.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com