Colorado justices weigh potential race-based treatment for Arapahoe County murder defendant

The Colorado Supreme Court considered a convicted defendant’s argument on Thursday that Arapahoe County prosecutors unconstitutionally singled out him and another Black teenager for murder prosecutions as adults, while offering lenient plea deals to the two non-Black co-defendants.

Lloyd Chavez IV, a student at Cherokee Trail High School, died in May 2019 after four teenagers attempted to rob him during a meetup to purchase vaping supplies. Evidence pointed to Demarea Mitchell as the one who fatally shot Chavez, but jurors also convicted Kenneth Alfonso Gallegos of felony murder for his participation in the robbery.

The remaining two defendants cooperated with law enforcement and Arapahoe County prosecutors refiled their charges in juvenile court. Those defendants, who were Hispanic or White, subsequently pleaded guilty and only served two years of juvenile incarceration.

Mitchell and Gallegos, in contrast, both received life sentences.

“They provided the non-Black co-defendants plea bargains and they all pointed at my client,” defense attorney Patrick R. Henson told the Supreme Court during oral arguments. “And if they never gave him the opportunity and they only gave that opportunity to the non-Black defendants, that is some evidence of discriminatory effect.”

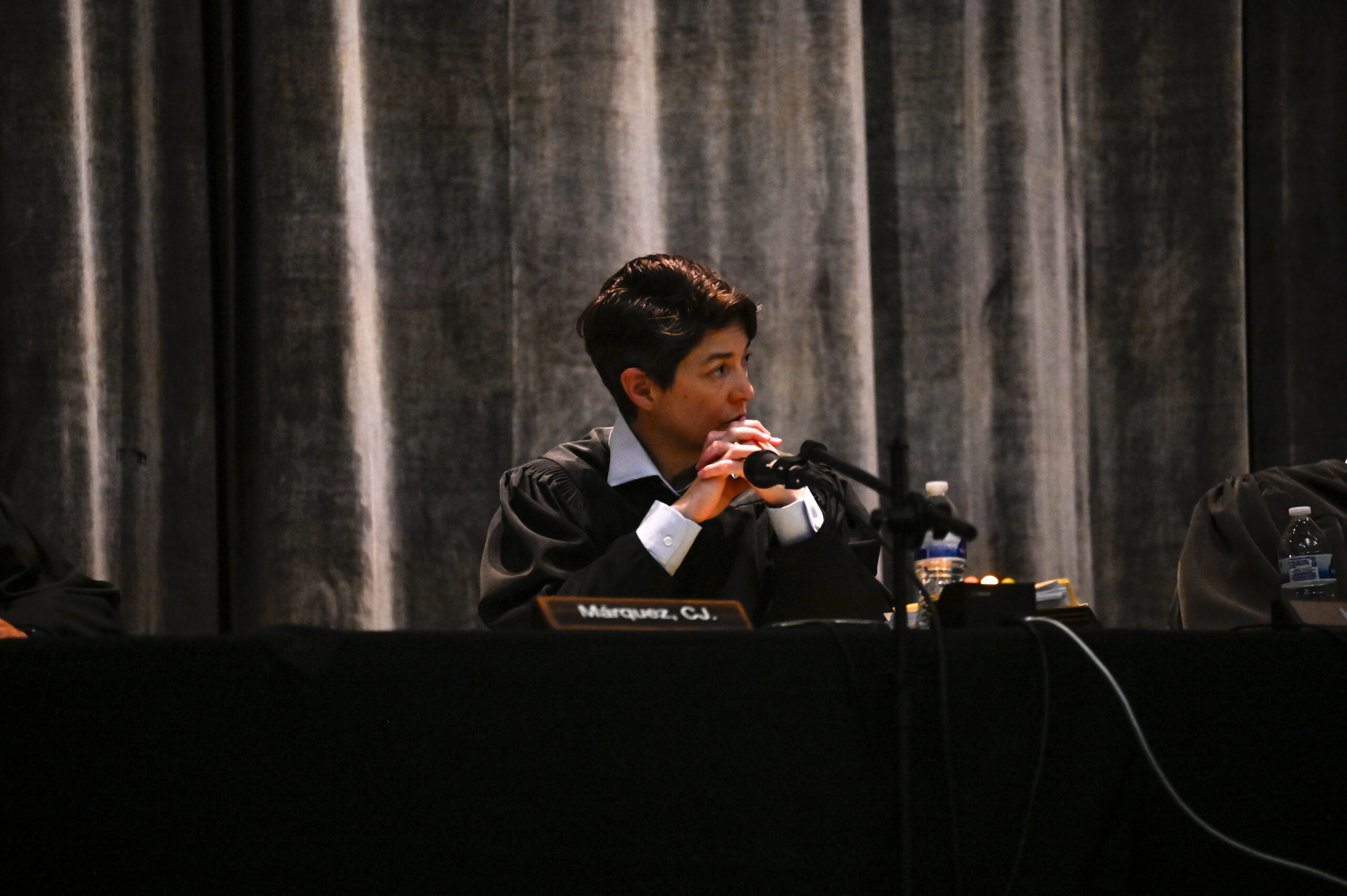

However, Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez wondered how the court should determine if Mitchell was similarly situated to his non-Black co-defendants, which was key to analyzing whether prosecutors treated him differently because of his race.

“I’m thinking of a bank robbery situation where things go south, someone dies,” she said. “The person who literally drove the getaway car, didn’t enter the bank, didn’t wield the gun, didn’t shoot anyone …. you would say that person is still similarly situated for your purposes because they were involved in the same criminal incident.”

Mitchell originally sought to dismiss the charges on the grounds that prosecutors violated his equal protection rights under the U.S. Constitution. Allegedly, the inability to have his case transferred to juvenile court was based on Mitchell’s race.

District Court Judge Ben L. Leutwyler disagreed, noting Mitchell was not in an identical position as the two non-Black defendants.

“There is evidence that supports a finding that Mr. Mitchell is the participant who actually shot and killed Mr. Chavez,” he wrote at the time. “Consideration of that fact alone is sufficient to find that the defendant is not similarly situated to the individuals who drove to the scene but did not otherwise participate in the robbery and murder of Mr. Chavez.”

A three-judge Court of Appeals panel agreed with Leutwyler’s reasoning that the prosecution’s differential treatment of Mitchell was justified given his role as the likely shooter. Moreover, the two non-Black defendants cooperated with prosecutors.

To the Supreme Court, Henson said there was some conflicting evidence about the shooter’s identity. Further, he argued the fact that prosecutors sought cooperation from the two non-Black co-defendants, but allegedly not from the two Black defendants, was itself discriminatory.

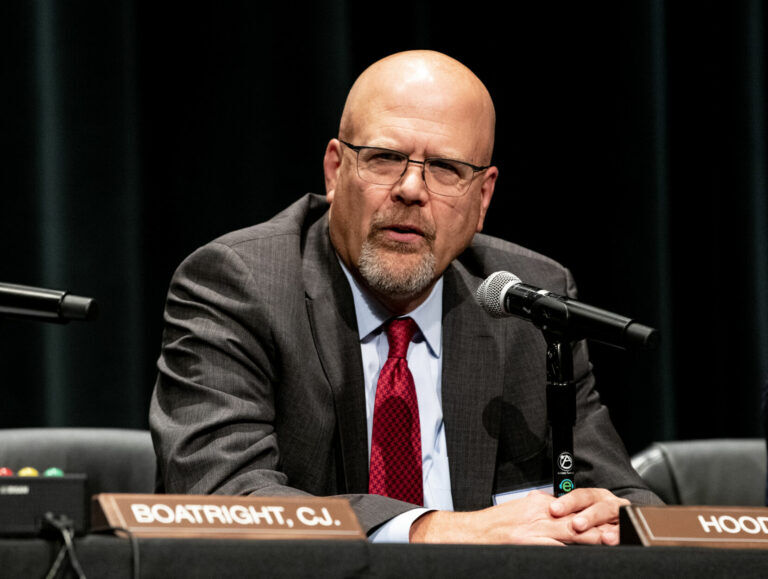

“Can you tell us whether Mr. Mitchell ever sought to cooperate?” asked Justice William W. Hood III.

“I have no record of it,” replied Henson, adding that he imagined any trial attorney would have pursued that option if it were available.

Assistant Attorney General Brenna Brackett said the prosecution likely needed to extend plea offers to certain defendants to effectively pursue the case. She suggested it would be inadvisable to subject their multifaceted decisions to second-guessing, especially when one co-defendant has been alleged to commit a more serious act.

“One concern I have is that standard is so easily met,” said Márquez. “There are many, many factors that go into extending plea offers and charging decisions. Is the bar so low that the prosecution can meet it in every case and a defendant never truly has the chance to make a selective prosecution claim?”

“This is an executive power. The prosecution makes determinations about plea bargaining, and that is why it’s entitled to so much deference,” said Brackett.

In his written brief, Henson cited statistics from Arapahoe County between 2012-2020 showing Black juveniles were more likely to be prosecuted as adults and more likely to receive prison sentences. He contended that, unless the court dismisses the case outright for selective prosecution, Mitchell should be entitled to evidence specific to his case as well as broader racial statistics related to charging decisions.

“My concern would be if you look broadly enough,” said Justice Richard L. Gabriel, “you can certainly look at the United States and find a minority population, the Black population, tends to be overrepresented in prisons. And you probably would see that everywhere.”

The arguments took place at East High School in Denver as part of the long-running “Courts in the Community” program. During a question-and-answer session with students afterward, Henson said even if Mitchell prevails, the case would likely return to the trial court for an opportunity to prove selective prosecution based on race.

“The remedy in the law is unclear,” added Brackett.

Justices Melissa Hart and Carlos A. Samour Jr. did not attend the arguments, although Márquez said they intend to participate in the decision. A judicial department spokesperson said both were absent for personal reasons. Samour’s clerks, who served as bailiffs for the proceedings, were all wearing masks, suggesting illness was a factor.

The case is Mitchell v. People.