Colorado Supreme Court dings El Paso County DA’s office for filing appeal in wrong court

El Paso County prosecutors incorrectly filed an appeal with the Colorado Supreme Court, the justices ruled on Monday, explaining that a trial judge did not, in fact, declare a law unconstitutional and enable the state’s highest court to hear the case directly.

Under state law and the procedural rules, district attorneys have a duty to appeal to the Supreme Court whenever a trial judge declares “any act” of the legislature unconstitutional.

However, the Supreme Court clarified that the judge hearing Ashley Hernandez’s criminal case did not find the law criminalizing threats against a judge to be unconstitutional across the board.

“Rather, the court concluded that the charge against Hernandez was unconstitutional because it sought to criminalize protected nonthreatening speech,” the court wrote in an unusual unsigned opinion on April 14.

Consequently, the justices told the Fourth Judicial District Attorney’s Office that it should have appealed the dismissal of Hernandez’s charge like normal in the Court of Appeals. It then transferred the case to the appellate court itself.

The erroneously filed appeal touched on the two ways in which laws can be deemed unconstitutional. A “facially” unconstitutional law means it is unconstitutional in every situation. But a law is unconstitutional “as applied” if it results in an unconstitutional outcome for a specific litigant.

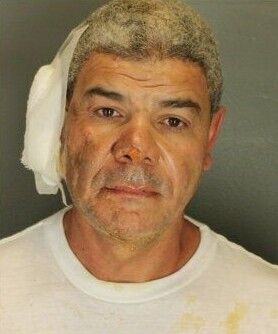

Prosecutors charged Hernandez based on a brief 2023 elevator ride at the Colorado Springs courthouse with District Court Judge Diana May. May had presided over a criminal case in which Hernandez’s romantic partner was the defendant. May eventually recused after hearing about a jailhouse phone call to Hernandez in which the defendant claimed May was on “the compromised judge list.”

Two months later, Hernandez and May got on the same courthouse elevator and Hernandez asked the judge to “comment why you were biased” on her partner’s case. May said she could not comment because “that would be unethical.” Hernandez replied that “you taking that case” was unethical, and “what’s inappropriate is you waking up next to a cop every day and going in there.”

May reported the encounter to security and prosecutors charged Hernandez with retaliation against a judge based on the audio from the elevator. After Hernandez moved to dismiss, the district attorney’s office amended the charge to allege Hernandez made a credible threat against May.

The defense again moved to dismiss, citing the 2023 U.S. Supreme Court decision of Counterman v. Colorado. The stalking case, which originated in Arapahoe County, culminated in the Supreme Court’s recognition that prosecutors must prove a defendant was aware of the threatening nature of their statements. Otherwise, defendants could be convicted for constitutionally protected speech.

Dinsmore Tuttle, a retired judge assigned to Hernandez’s case, found the evidence “falls far short” of establishing a threat. Therefore, she concluded, Hernandez’s confrontational comments “are protected speech, and the charge against her is unconstitutional as applied.”

The district attorney’s office immediately appealed to the state Supreme Court, citing the requirement that the justices directly consider instances where trial judges declare laws unconstitutional. But the Supreme Court asked the parties to explain why it, and not the Court of Appeals, was the correct forum to hear the appeal.

It is not, responded defense attorney Christopher Gehring, “since the trial court found only that, under the specific circumstances of this case, Ms. Hernandez’s speech is protected and therefore cannot be prosecuted.”

It is, countered Senior Deputy District Attorney Doyle Baker, because “a successful as-applied challenge impairs a criminal statute’s ability to function as the legislature intended.”

It is not, the Supreme Court decided.

“We conclude that dismissal of a criminal count on the grounds that it is unconstitutional as applied must be appealed, if at all, to the court of appeals,” the justices wrote. The Supreme Court’s authority to directly hear cases applies “to situations in which a district court has declared a statute to be facially unconstitutional.”

The case is People v. Hernandez.