DNA state crime lab debacle leads to first hearing alleging innocence

Yvonne “Missy” Woods was nearly nine years into her career as a DNA scientist with the Colorado Bureau of Investigation when she took the stand on Oct. 17, 2002, to admit a major embarrassment in her work – one she testified came as a “blow to my ego.”

A masked man, using what police said appeared to be a screwdriver, had broken through the front door of a woman’s trailer at a Lakewood trailer park about 1 a.m. on April 23, 2002, and had forced the woman and her 5-year-old daughter to drink alcohol. Over several hours, the assailant repeatedly raped the woman and sexually molested her daughter in front of her. Armed with a knife, the man repeatedly slashed the woman’s breasts and sexually assaulted the woman with a ketchup bottle before fleeing with some of her money.

Solely based on the sworn statement of Woods, Jefferson County District Court Presiding Judge Roy Olson approved an arrest warrant for the man who lived with his wife in the trailer next to the victim’s. Woods in her sworn statement said her microscopic analysis of two pubic hairs recovered from the rape victim showed they matched pubic hairs from the victim’s next-door neighbor, James Hunter, then 43, who had willingly let Lakewood police collect samples from him after police targeted him as the top suspect for the crime.

During the probable cause hearing held months after the rape, Woods testified that her original analysis was flawed. A lab in Pennsylvania had tested the hairs for DNA and had found the hairs could not have come from the defendant and instead likely came from the victim.

Judge Olson, upon learning of the reversal in Woods’ original analysis, refused to forward the case on for a criminal trial and freed Hunter from jail, saying that without a match of the pubic hairs to the defendant “there’s not much of a case here.”

James Hunter is serving a 168-year prison sentence for a crime he contends he did not commit. Lawyers argue in court filings that DNA analysis by Yvonne “Missy” Woods was flawed.

Undeterred, Woods and prosecutors would two months later take the case to a grand jury, citing new evidence. They secured an indictment and an eventual conviction on burglary and sexual assault charges. Hunter was sentenced to 168 years to life in prison. So far, he has been incarcerated for more than 20 years and currently is serving time in Colorado’s Territorial prison in Cañon City.

Now defense lawyers are pushing to overturn that conviction, one of more than a thousand criminal cases now under scrutiny following the disclosure last week that the Colorado Bureau of Investigation has found Woods deviated from standard protocols and tampered with DNA results, omitting facts in official criminal justice records.

“This discovery puts all her work in question,” CBI officials said in a press release on Friday detailing the agency’s concerns with Woods, a former 29-year veteran of the state crime lab who retired on November 6, nearly a month after agency officials placed her on administrative leave.

Anomalies identified in Woods’ work prompted the CBI to ask state legislators in January to provide the state agency an additional $7.5 million to support the review and retesting of an estimated 3,000 DNA samples by an independent third-party laboratory and to pay for post-conviction reviews and potential retrying of criminal cases.

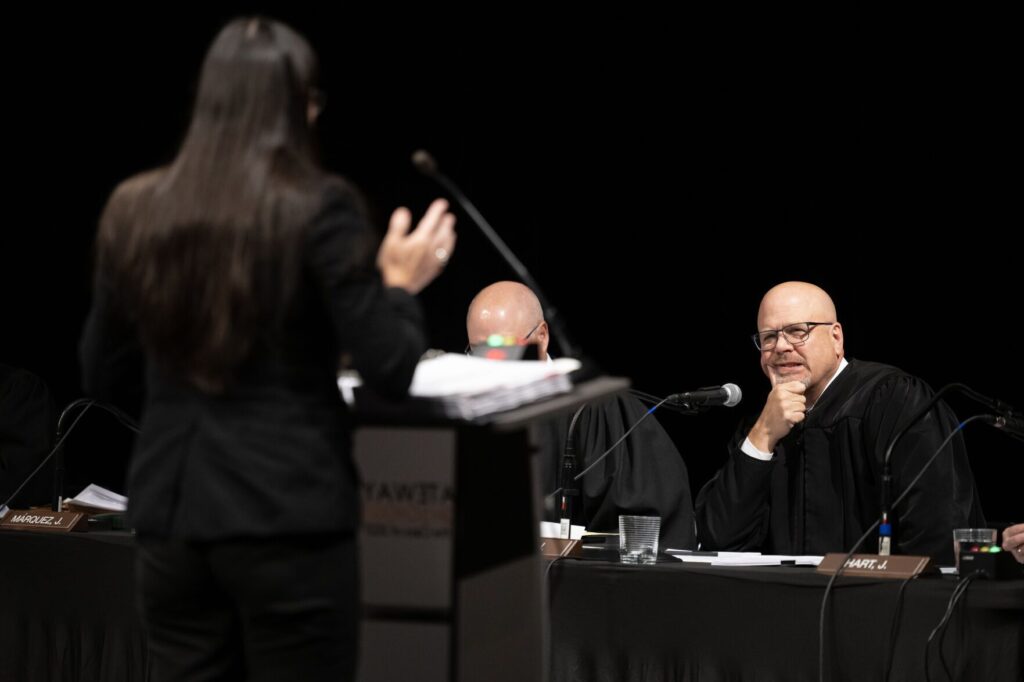

Hunter’s case appears to be the first to come up for a hearing in which defense lawyers argue the work of Woods resulted in the conviction of an innocent person. On Wednesday, U.S. District Judge Magistrate Michael Hegarty will hold a hearing on allegations that DNA evidence ultimately used to convict Hunter was so flawed that Hunter should get a chance to conduct new DNA testing on crime scene evidence, among other issues.

Lawyers representing Hunter say there is compelling evidence showing he was wrongly convicted and sentenced. They argue in federal court filings that the true culprit of the crime likely is a convicted sex offender serving 118 years in prison in Missouri who was in the same Lakewood trailer park where the crime occurred during the early morning hours that the crime occurred.

After the judge freed Hunter back in 2002, police, Woods and prosecutors did not give up on making a criminal case against Hunter.

Woods would go on to testify before a grand jury, and then during a criminal trial, stating that other evidence she tested for DNA after Hunter’s release from jail tied him to the scene of the rape.

Hunter, who was married, lived in the trailer next to the victim. He brought a plant over to her the morning that she returned from the hospital that administered a rape kit. He sat for nearly an hour with her offering to comfort her.

He became a top suspect in part because when the victim was put under hypnosis, she told Lakewood police that something in the voice of her assailant, who wore a white hood throughout the attack, sounded “a little” like her next-door neighbor, but that there also was something about his voice that didn’t sound like him. In addition, Hunter often referred to her as gorgeous. Years earlier, he also pleaded guilty to trying to burglarize a home while masked when he lived in Washington.

In Dec. 2002, two months after his release by the judge, Hunter was indicted by a grand jury after the CBI data scientist Woods testified. She said other additional hairs recovered from the scene of the crime – including one from a couch in the victim’s living room and one from a bed in her bedroom — had now been tested by her. She said one of the hairs had DNA that matched Hunter’s DNA. Her testimony was the sole physical evidence tying Hunter to the scene of the crime.

Now, in a filing with the U.S. District Court in Denver, defense lawyer Kenneth Mark Burton claims the additional DNA evidence Woods ended up providing is “unreliable due to it being fabricated and planted.” Burton in an interview said he is confident that the hair fibers came from a packet of hairs police collected from Hunter’s own body.

Burton attached to one of his court filings an exhibit that is an actual evidence log from the case. The evidence log shows Lakewood police crime techs also were confused back during the criminal case about the source of the new hairs Woods analyzed and then returned to Lakewood police.

Notes on the evidence log, submitted as an exhibit, show Lakewood police crime techs wondered why the CBI had returned two packets of hair and fiber when there was only one crime scene evidence packet. Notes on that evidence log reflect that one of the investigating officers “separated items from original packet” and had another detective take it to CBI officials, who then returned the new packet.

In addition, the defense lawyer claims that prints taken from the forced point of entry into the victim’s trailer and fingerprints from inside the trailer never were submitted to the national Automated Fingerprint Identification System despite former Jefferson County Assistant District Attorney Steven Jensen saying in court filings that had been done. Jensen originally prosecuted the case.

Jensen, in an interview, said he “did not make any misrepresentation that I’m aware of” and said, “Sometimes you have to rely upon information that you were provided by other people.”

The former prosecutor said regardless of any discrepancy over how the fingerprints were handled, he stands by the prosecution and believes Hunter’s guilt remains “overwhelming.”

Broken wheelchairs plague disabled air travelers

Lawyers for the Jefferson County District Attorney’s Office and police in court filings have resisted efforts to submit crime scene material for new DNA testing and to submit fingerprints to the national database. They contend that Hunter should instead seek relief in Colorado’s court system, where his appeals already have been unsuccessful. Chris Schaefer, the CBI director, did not respond to requests for comment submitted to his spokesperson.

Ryan Brackley, a lawyer representing Woods, also says his client “never created or falsely reported any inculpatory DNA matches or exclusions, nor has she testified falsely.” He added that his client is cooperating with an investigation into her work.

Lawyers in court filings assert that they believe Kenneth Dale Smith, a convicted sex offender serving time in a Missouri prison, is the true culprit of a 2002 rape at a Lakewood trailer park.

Burton and another defense lawyer, though, say the failure to submit the prints to the national database is critical. They contend the prints must be submitted to the national database, and that the defense also should be allowed to conduct new DNA analysis on material recovered from the victim and her trailer because they have another suspect. They also are pressing to have the CBI release details of an internal affairs investigation into Woods, which state officials so far have refused to release to the public.

They say the crime scene fingerprints and new DNA testing would likely identify the culprit as Kenneth Dale Smith, 44, who pleaded guilty in January 2016 in a Missouri courtroom in Lafayette County to multiple charges of domestic assault, tampering with a victim, statutory rape, statutory sodomy, child molestation and child abuse.

Thomas Henry, a lawyer who previously represented Hunter, said crimes Smith is convicted of had similarities to the attack and rape in Jefferson County years earlier.

A bottle was used in the sexual assaults in Missouri, and the victims’ breasts were slashed with a knife, the defense lawyer said. Further, he went to meet Smith in person and told him he was pressing to get the fingerprints that came from the Colorado crime scene processed through the national database.

“He basically said, ‘Well that’ll probably tell,’” Henry recalled, adding that Smith didn’t want to say more because he had an appeal pending.

Smith was one of several people present in the trailer park the night of the violent rape that occurred in Colorado in 2002. A long-haul trucker who worked with Hunter, Smith had been partying with Hunter and several other people that night, according to the lawyer. Witnesses said Hunter’s sister put an inebriated Hunter in his bed late that night, where he was found the next morning. Smith had disappeared by the next morning, according to the lawyer.