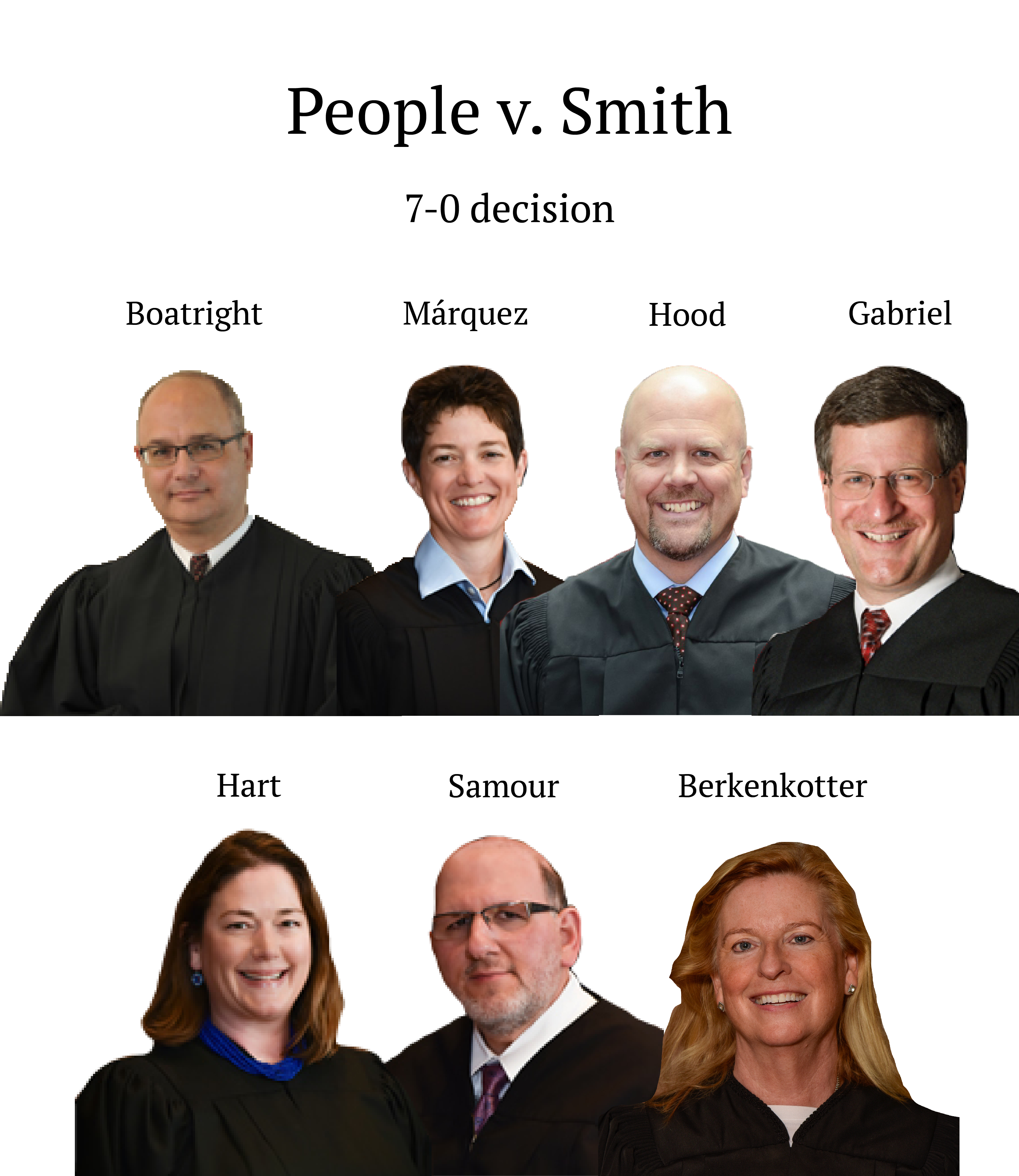

Colorado Supreme Court upholds ability of defense lawyers to abandon clients’ claims without consent

The Colorado Supreme Court made it easier on Monday for criminal defense lawyers seeking postconviction relief on behalf of their clients to abandon any claims they wish, even over the client’s objection.

Noting courts have long treated trial lawyers as the “captain of the ship,” the Supreme Court clarified that defense attorneys appointed to pursue postconviction relief are free to discard some of a defendant’s prior claims as part of the case’s “strategy.”

“Counsel has the right to make these kinds of tactical decisions even if the client disagrees with them,” wrote Justice Richard L. Gabriel in the Jan. 22 opinion.

A defendant may file claims challenging his conviction or sentence under certain circumstances, including for ineffective assistance of counsel or newly discovered evidence. If a trial judge determines any claim has merit and the defendant has requested counsel, the judge must forward the petition to an appointed attorney. The responsibility then falls to the attorney to investigate the allegations and, under the rules, “add any claims” that are viable.

The question for the Supreme Court was what should happen when an appointed attorney chooses to focus on only some claims, but not others. In that circumstance, has the lawyer abandoned the remaining allegations their client made originally, such that a judge no longer has to consider them?

In a statement, the Colorado Criminal Defense Bar said the “universal belief” among appointed attorneys was that their job is to supplement, not supplant, the claims their clients made when they were self-represented, or “pro se.”

“The Supreme Court’s ruling now requires counsel to place a statement in the supplement, pointing out that counsel is not abandoning the client’s pro se claims,” wrote attorney Hollis A. Whitson on behalf of the organization. “The ruling itself may not prove to be too burdensome for appointed counsel. However, the way in which the new rule has been implemented – disrupting settled expectations and longstanding practice – raises significant concerns about basic fairness.”

In the underlying case, a Larimer County jury convicted Anthony Robert Smith of multiple child sex assault offenses. He then filed a motion in 2018 asserting his trial lawyer was ineffective, there was new evidence and prosecutors committed misconduct. After the court appointed an attorney to assist, she filed a supplemental motion focusing on only a portion of Smith’s claims.

District Court Judge Gregory M. Lammons subsequently decided that, because Smith’s new lawyer had not engaged with the other allegations, Smith waived his ability to have Lammons look at them.

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals acknowledged Smith’s court-appointed attorney had no duty to advocate for meritless arguments. However, it was not the case, wrote Judge Rebecca R. Freyre, that Smith forfeited his ability to have Lammons consider all of his original claims, or that Smith’s lawyer received “informed consent to waive any claims.”

The prosecution then appealed, citing the Supreme Court’s previous characterization of attorneys as the “captain of the ship,” who have latitude to represent their client’s interests – even if that means abandoning long-shot claims.

During oral arguments last year, the justices wondered how a client’s “informed consent” would work in practice. On the other hand, members expressed concerns about giving trial judges an easy path to dismissing a defendant’s claims whenever an appointed attorney does not explicitly request consideration of their client’s original arguments.

Ultimately, while the Supreme Court noted defense attorneys may not gut the entirety of their clients’ claims unilaterally, the choice to abandon certain arguments fell under the umbrella of tactical decisions to be made by the “captain of the ship.”

That principle “does not require an attorney to obtain her client’s informed consent,” Gabriel wrote. Therefore, “counsel was not required to obtain Smith’s approval – much less his informed consent – to decide which postconviction claims to pursue and which to abandon.”

The Colorado Criminal Defense Bar, in its statement, said that while attorneys are on notice going forward that they must explicitly indicate a desire to preserve their clients’ original claims, the Supreme Court’s decision negatively affects defendants whose appeals are currently pending.

Defendants and their lawyers “are understandably blindsided by the abrupt adoption of a retroactive rule that is the opposite of what they have been advising the clients. The clients, the attorneys and the taxpayers deserve better.”

The case is People v. Smith.