Colorado’s justices disqualified Trump from the ballot. Now what? | ANALYSIS

Roughly a decade ago, the 10th Circuit Court entertained a case about a New York resident who wished to become America’s next president.

The man wanted his name on Colorado’s presidential ballot for the 2012 election. But there was one problem. He was a naturalized citizen.

So, the Colorado Secretary of State told him he was ineligible because he needed to be a natural-born citizen to hold the office of the American president.

Abdul Hassan sued, lost in district court and then appealed.

The appellate court’s order, which affirmed the ruling against Hassan, was short.

“As the magistrate judge’s opinion makes clear and we expressly reaffirm here, a state’s legitimate interest in protecting the integrity and practical functioning of the political process permits it to exclude from the ballot candidates who are constitutionally prohibited from assuming office,” the appellate court said.

Neil Gorsuch, then a judge on the appellate court, wrote that ruling.

On Tuesday, the Colorado Supreme Court quoted precisely those words from Gorsuch, who now sits on the U.S. Supreme Court, in its decision to disqualify Donald Trump from Colorado’s presidential ballot.

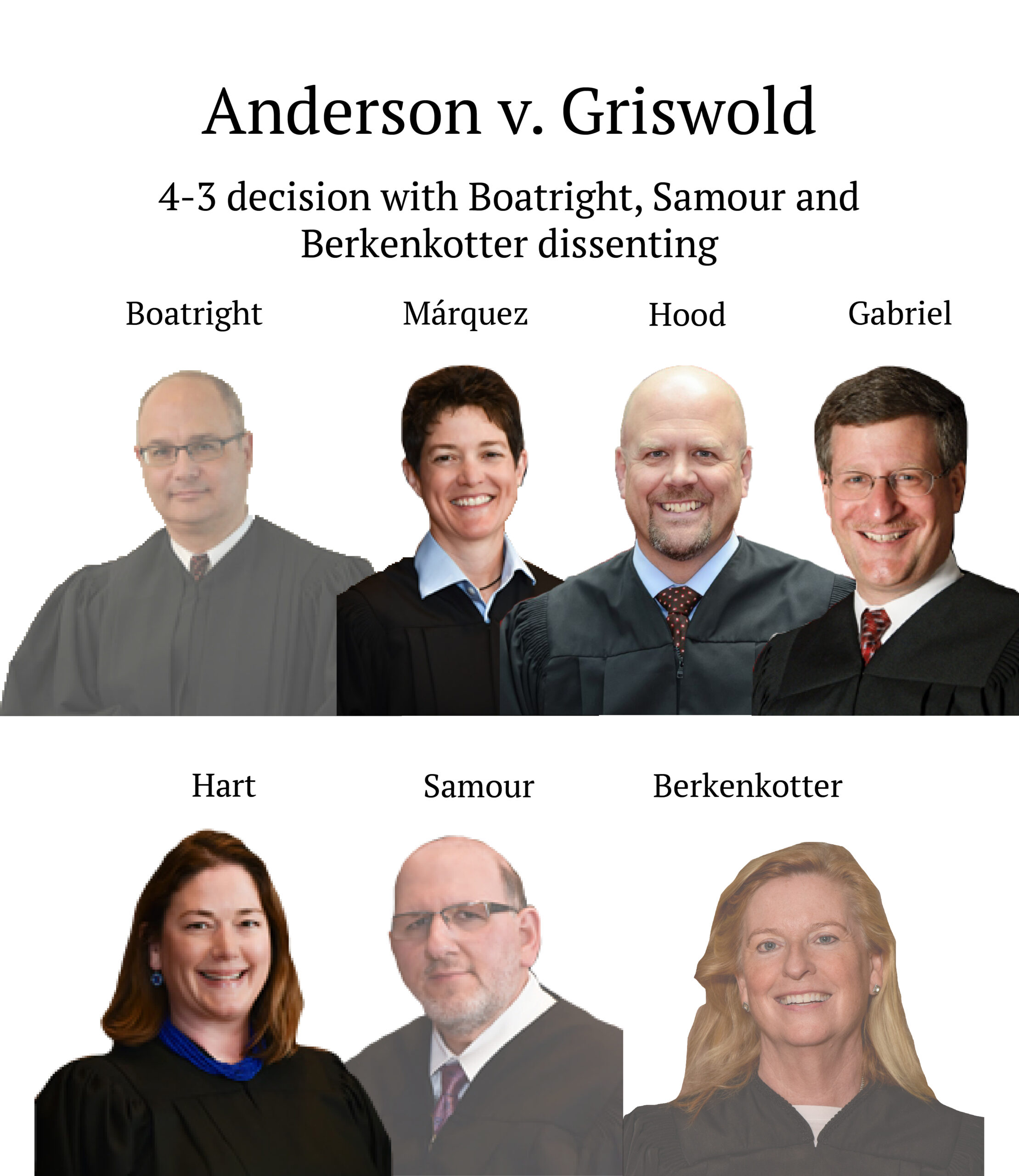

Trump’s campaign already said it would appeal the 4-3 decision, and the Colorado Supreme Court, anticipating as much, decided to stay its order until Jan. 4.

While Colorado’s justices noted Hassan v. Colorado, the case against Trump – assuming the former president, indeed, files an appeal and the U.S. Supreme Court accepts the case – offers a far more complex set of issues that Gorsuch and other justices must contend with.

The Colorado Supreme Court’s decision to disqualify Trump from the state ballot hinges on several crucial conclusions – notably that the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol constituted an “insurrection,” that the former president “engaged in” that act, and his speech was “not protected” by the First Amendment.

In reaching these conclusions, the majority rejected Trump’s argument that the district court’s proceedings failed to provide the time necessary to litigate such a complex case, insisting the district court “took many steps to address the complexities of the case.”

It’s precisely this point that vexed Colorado’s justices who dissented from the majority, arguing that the plaintiff’s claims “cannot be squared” with the state’s own timelines for adjudicating election cases.

In his dissent, Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright said questions over age or citizenship – such as the one raised in Hassan – are “characteristically objective, discernible facts.”

“Conversely,” he wrote, “all these questions pale in comparison to the complexity of an action to disqualify a candidate for engaging in insurrection.”

What will the U.S. Supreme Court do?

It’s always precarious to try to predict a Supreme Court ruling. The high court is comprised of six justices appointed by Republicans, including three nominated by Trump himself. Partly because this is completely new legal ground, it’s hard to predict how individual justices will rule based on their ideology.

Some of the strongest advocates of using Section 3 against Trump have been prominent conservative legal theorists and lawyers who argue that courts have to follow the actual words of the Constitution. Here, they argued, there’s no wiggle room – Trump is clearly disqualified.

The petitioners who brought the case – four Republican and two unaffiliated voters – argued Trump cannot hold the presidency again under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, ratified in the wake of the Civil War. Section 3 disqualifies senators, U.S. representatives and “an officer of the United States,” among others, from holding future federal or state office if they took an oath to support the Constitution and subsequently “engaged in insurrection.”

Consider this: The Colorado high court’s seven justices were all appointed by Democrats. But they split, 4-3, on the ruling. Courts are often very hesitant to limit voters’ choices. There’s a term for that – the “political question,” whether it’s better for lawmakers to settle a dispute than judges. In fact, that’s one reason all the other Section 3 lawsuits had failed so far.

Sometimes, courts have dodged the essential question. That’s what happened in Minnesota, where the state Supreme Court allowed Trump to stay on the ballot because, it found, the state party can place whomever it likes on its primary ballot. A Michigan appeals court came to the same conclusion. A New Hampshire judge dismissed a lawsuit by a little-known longshot Republican presidential candidate, saying the question of whether Trump belonged on the ballot is “non-justiciable.”

What’s the immediate effect of the ruling?

So far, very little in the real world. Aware that the case is very likely going to the U.S. Supreme Court, the 4-3 Colorado Supreme Court stayed its order until Jan. 4 – the day before Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold must certify the candidates for next year’s presidential primary.

The U.S. Supreme Court could rule sooner, providing clarity to Griswold’s office.

Technically, the ruling applies only to Colorado, and secretaries of state elsewhere have issued statements saying that Trump remains on the ballot in their state’s primary or caucus.

But it could embolden other states to try and knock Trump off the ballot. Activists have asked state election officials to do so unilaterally, but none have. Dozens of lawsuits have been filed, but all failed until Colorado.

The U.S. Supreme Court has never ruled on the meaning of Section 3. The justices can take the case as quickly as they like once Trump’s campaign files its appeal, which is not expected this week. The high court then could rule in a variety of ways – from upholding the ruling to striking it down to dodging the central questions on legal technicalities. But many experts warned that it would be risky to leave such a vital constitutional question unanswered.

“It is imperative for the political stability of the U.S. to get a definitive judicial resolution of these questions as soon as possible,” Rick Hasen, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, wrote shortly after the ruling. “Voters need to know if the candidate they are supporting for president is eligible.”

What might the justices focus on?

The Colorado Supreme Court honed in on several points, any one of which could provide the country’s justices the entryway to decide whether to uphold or deny the state ruling:

? Whether Colorado’s “Election Code” allows the challenge to Trump’s status as a qualified candidate based on Section 3.

? Whether Congress needs to pass implementing legislation on Section 3’s disqualification provision or whether the provision is self-executing.

? Whether judicial review of Trump’s eligibility under Section 3 is precluded by the “political question” doctrine.

? Whether Section 3 applies to the presidency or to someone who has taken the oath as president. (The district court said it does not, a conclusion the justices reversed.)

? Whether the district court abused its discretion in admitting portions of Congress’s Jan. 6 report into evidence during trial.

? Whether the district court erred in concluding that the Jan. 6 attack constituted an “insurrection.”

? Whether district court erred in concluding that Trump “engaged in” that “insurrection.”

? Whether Trump’s speech “inciting the crowd that breached the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021” was protected by the First Amendment.

In all of these points, Colorado’s justices ruled against Trump.

A question over due process

The country’s justices might also wade into one central question that Colorado’s justices explored – whether the district court afforded Trump due process, particularly in light of the state’s own expedited timelines for hearing election cases.

Just because an election case is expedited, the majority argued, “does not mean these proceedings lack due process.” In fact, the majority said, the district court took “many steps to address the complexities of the case,” such as by adopting a civil-case-management approach, which afforded the parties the “opportunity to be heard on a wide range of substantive issues.”

The district court, the majority concluded, “admirably – and swiftly – discharged its duty to adjudicate” the case.

“If any case suggests that it is not impossible to ‘fully litigate a complex constitutional issue within days or weeks,’ this is it,” the justices said.

Justice Carlos Samour, who dissented, argued otherwise.

“Based on its interpretation of Section Three, our court sanctions these makeshift proceedings employed by the district court below – which lacked basic discovery, the ability to subpoena documents and compel witnesses, workable timeframes to adequately investigate and develop defenses, and the opportunity for a fair trial – to adjudicate a federal constitutional claim (a complicated one at that) masquerading as a run-of-the-mill state Election Code claim,” Samour wrote.

Boatright, who maintained that the district court failed to meet statutory timelines, quipped, “It is no mystery why the statutory timeline could not be enforced: This claim was too complex.”

Michael Karlik of Colorado Politics contributed to this report.