‘A unique ability to change the world’: Colorado’s justices talk to students about law, life experiences

When roughly a third of the students sitting in Aurora’s Gateway High School auditorium raised their hands to say they were thinking of going to law school, it was no surprise to their teacher, Leland Tulper.

“A lot of them were mock trial kids, which was great,” said Tulper, a social studies instructor and mock trial coach who helped orchestrate the Colorado Supreme Court’s visit to the school on Thursday. “That’s basically who was here: The kids who were interested in law, interested in what was going on, high-level, high-functioning kids who are most likely going to college.”

As part of its 37-year-old Courts in the Community initiative, the Supreme Court travels outside of downtown Denver twice per year to hear oral arguments in real cases, typically at a high school in front of an audience of students. Arapahoe County Magistrate Echo Ryan, herself an Aurora Public Schools graduate, provided opening remarks for the court’s first trip to Gateway since 2006.

The juniors and seniors in attendance sat quietly, while each of the hour-long arguments unfolded – one case about a slip-and-fall accident in a parking garage and the other about a thief who rode off on a stolen bicycle, only to crash into a car when the victim chased him down. When it was time for the students to interrogate the lawyers afterward, their questions were as pointed as the justices’.

“I would imagine a $6,000 bike would have brakes on it. Why didn’t he use them?”

“Do you think he would have actually stopped, given that his actions already weren’t reasonable because he stole a bike from someone else?”

“Where would you draw the line at what’s acceptable for someone to do when trying to get their property back?”

At one point, the students’ questioning elicited rare praise from one of the parties against their opponent. The lawyer for a woman who injured herself in a Jefferson County parking garage expressed gratitude that, even as the county fought his client’s lawsuit, it had fixed the original hazard.

“The county did react. They did try several different things in order to make this more safe. The issue of legal liability and moral responsibility – I think Jefferson County absolutely did everything they could regarding the latter,” said Thomas A. Bulger.

The justices themselves also fielded questions. While the members of the Supreme Court could not speak about the cases they just heard, they instead responded to inquiries about how and why they became judges in the first place.

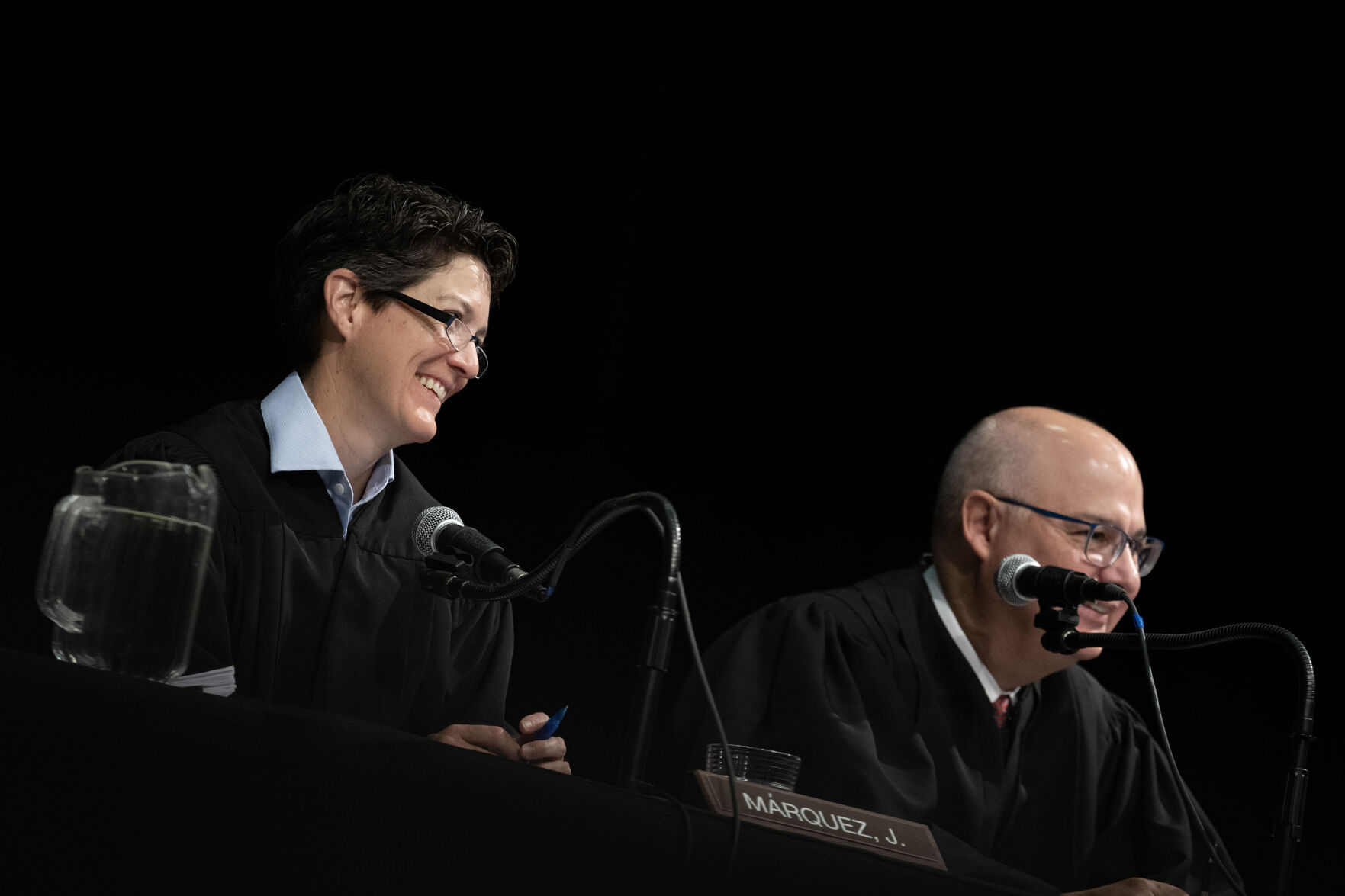

“I was appointed in 2010. I was 41 years old – so, younger than normal for folks coming to this court,” said Justice Monica M. Márquez. “I was also the first Latina to be appointed to this court and openly LGBT. In 2010, that LGBT piece, that was daunting, I’ll just put it that way.”

She added that the culture has changed, but 13 years ago “it took a lot of courage to go through that process as an openly LGBT individual and risk that either the governor wouldn’t be interested in choosing me or the (nominating) commission wouldn’t want me there.”

“One of the great things about being a lawyer is lawyers have a unique ability to change the world,” said Justice Richard L. Gabriel. “There’s a reason lawyers formed most of the great democracies in world history.”

Tulper believed that sentiment resonated with his students, saying many of them are genuinely interested in the court’s work.

“These are kids that truly want to change the world,” he said. “The questions they’re asking, they’re truly passionate about it. They’re not just asking to ask. There was no prep beforehand to ask questions. So this was all the kids.”

To that end, one student asked the members of the Supreme Court how they avoid injecting bias into their decision making.

“It’s something you work at every day. I don’t think you reach a point where you go, ‘All right, I’ve been doing this five years now. I’m good to go. I don’t have to worry about biases,'” responded Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr.

Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright encouraged the students to think about a career in the judicial branch, which encompasses probation officers and support personnel in addition to judges. For those thinking of earning a law degree, Justice William W. Hood III assured them that a multitude of paths will be available to future attorneys.

“It’s kind of like the Swiss Army knife of professions,” he said.

La’Ray Clemmons, a junior, said she has an interest in becoming an attorney someday.

“I think it’s really cool how you have to think on the spot and see different versions of people’s reasoning,” she explained. “I am really good at debate. … I think it would be really fun to be in a position like that.”

Katalina Borso, also a junior, is more interested in becoming a surgeon than a lawyer. Nonetheless, she appreciated the opportunity to attend the event.

“Even though I don’t want to go into a law path, I still want to be a part of this because it’s a great experience,” she said.