Colorado Supreme Court rules 30-day eviction notice applies for federally supported housing

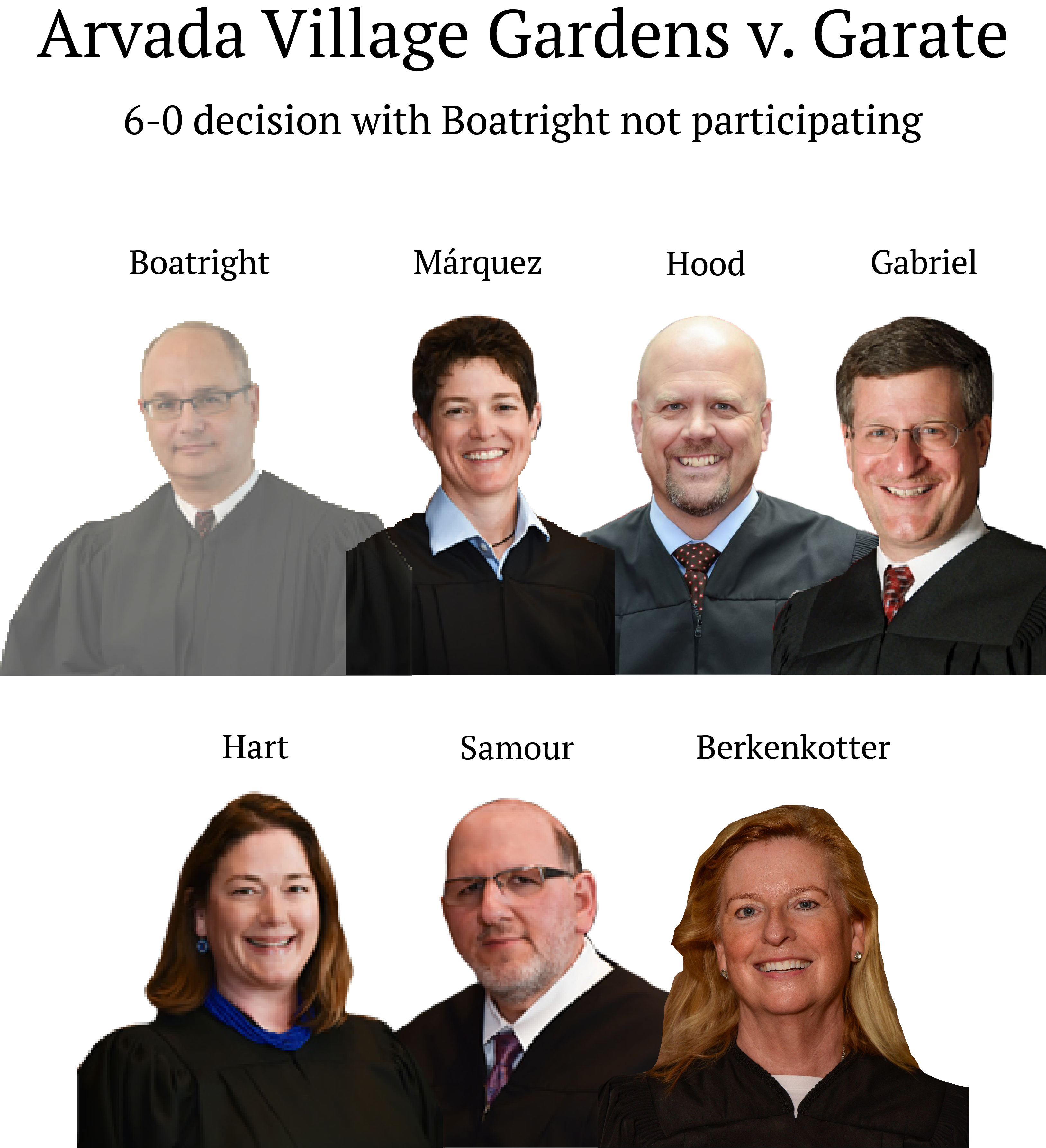

In a victory for tenants’ rights, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Monday that landlords must provide 30 days’ notice of an eviction for federally supported housing units, a requirement that Congress enacted in the early COVID-19 pandemic which has never expired.

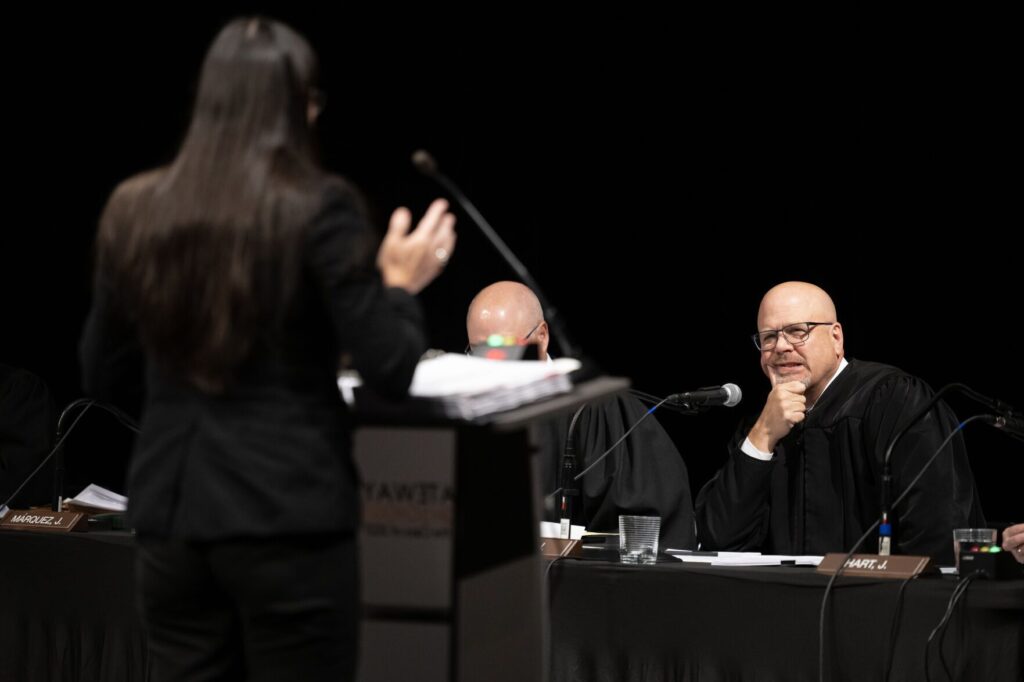

The decision appears to be the first of its kind from any state Supreme Court. Judges across the country, and even within Colorado, have reached different conclusions about whether the 30-day notice requirement enshrined in a major pandemic relief law continues to trump state-level notice windows – 10 days, in Colorado’s case.

Justice Melissa Hart, in the Supreme Court’s May 15 opinion, acknowledged Congress had explicitly allowed a related moratorium on evictions to expire in mid-2020.

“But the Notice Provision includes no expiration date. We cannot insert an expiration date where Congress omitted one,” she wrote.

“This is an incredible day for Colorado tenants,” said Spencer Bailey, an attorney for plaintiff Ana Garate. “This will give struggling families a much needed lifeline to get back on their feet and avoid eviction and displacement.”

In March 2020, Congress passed the CARES Act, an approximately $2 trillion economic relief measure prompted by the widespread shutdown of society as the deadly coronavirus began to spread.

In a section titled “Temporary moratorium on eviction filings,” Congress instituted a 120-day halt to evictions for properties subsidized by federal programs. The CARES Act also required landlords to provide 30 days’ notice to tenants to vacate those units before pursuing an eviction.

Since 2020, judges have been called upon to interpret whether the notice window expired along with the temporary eviction moratorium, or whether 30 days remain the law nationwide.

In the case before the Supreme Court, Garate’s landlord in Jefferson County, Arvada Village Gardens, gave her 10 days’ notice to vacate on Dec. 6, at which time she allegedly owed $804. Less than one month later, it moved to evict her in court. Garate, who receives a federally subsidized housing voucher through a program known as Section 8, argued the CARES Act’s 30-day notice period overrode the requirement of only 10 days’ notice in state law.

County Court Judge Sara M. Garrido issued a one-paragraph rejection of that reading, finding the 30-day notice in the CARES Act was “temporary.” Garate then quickly sought the intervention of the Supreme Court.

“In a typical year, over 40,000 evictions are filed in Colorado county courts. The applicability of the CARES Act to eviction proceedings in Colorado will affect thousands of cases,” wrote Bailey.

He elaborated that county courts across Colorado are unevenly applying the CARES Act. Without the Supreme Court’s intervention, Bailey argued Garate could lose her federal housing voucher and have an eviction listed on her record for landlords to see in the future.

Arvada Village Gardens did not respond to Garate’s petition, but a coalition of groups representing landlords – including the Colorado Apartment Association, the Apartment Association of Metro Denver and related regional organizations – filed a brief opposing the idea that an emergency pandemic law continued to override Colorado’s window for eviction notices.

“Permanently extending this time to 30 days will necessarily result in additional delays and expense in regaining possession of rental properties and hence in lost rental income, and will also result in delays in the turnover of residential rental properties during a time of severe rental housing shortage,” the landlord associations wrote.

However, there was evidence to suggest Congress, either inadvertently or on purpose, had not let the 30-day window terminate. Last year, the National Apartment Association acknowledged that a “drafting error” has allowed the window to remain in effect “long after” the eviction moratorium expired. There is also a bill pending in the U.S. House of Representatives that would repeal the 30-day notice period, which would be unnecessary if the provision were no longer in effect.

The state Supreme Court, however, did not need to look outside of the law’s text to determine Congress had clearly left the 30-day notice window intact.

“The statute’s title, ‘Temporary moratorium on eviction filings,’ doesn’t change anything,” Hart wrote. “By its own terms, the Moratorium Provision was temporary. But just because the word ‘temporary’ is in the title doesn’t mean that the Notice Provision must receive the same treatment.”

Jack Regenbogen, deputy executive director of the Colorado Poverty Law Project, called the court’s holding a “crucial safeguard” against evictions that he hopes will clarify the law for other courts in the country. A spokesperson for the National Apartment Association said it supports the proposed legislation to remedy the “drafting error” in the CARES Act.

Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright did not participate in the appeal.

The case is Arvada Village Gardens LP v. Garate.