AI in the exam room: blending technology with the human touch

As artificial intelligence has become more ubiquitous in everyday life — from a typical smartphone’s autocorrect function to chatbots that can simulate conversations with humans, quickly analyze data sets and more — it’s also changing how medical professionals and organizations provide health care, and the patient experience along with it.

Today, medical practitioners are using AI to schedule appointments, document patient visits, create discharge summaries and care plans, analyze medical images, and even to aid in diagnosing patients, for example.

Local business and medical experts agree that AI is here to stay, including in health care settings. But they also caution that humans must maintain oversight of artificial and augmented intelligence, using it as a tool to enhance the work they’re doing or the care they provide — not as a replacement for human beings or for personal connection.

“It’s not going away,” said Jonathan Liebert, chief executive officer and executive director of the Better Business Bureau of Southern Colorado. He met Dr. Vinh Chung, dermatologist and founder of Vanguard Skin Specialists, for an informal discussion in late October on the role of AI technology in health care and in everyday life. “I’ve never seen anything like this.”

Data from a survey of 1,183 practicing medical physicians nationwide, conducted by the American Medical Association in November 2024, found that 66% of physicians were using AI in their practice, compared with 38% in 2023.

The 2025 Physicians AI report, recently released by physician-led website Offcall, found that 67% of physicians surveyed use AI every day in their practice, 89% use it weekly, and 84% say it makes them better at their jobs. Just 3% never use it at all, according to the report. Offcall conducted the survey of more than 1,000 clinicians across 106 specialties in October.

The task ahead for business owners and medical providers is now to implement AI technology “responsibly and strategically,” Liebert said.

A second, related task is to look at the bigger picture: “What does this mean? How do we do this? Why are we doing this?” Liebert said.

Chung cautioned: “With AI, as it comes on, I think we really need to draw a line. When is it harmful? When is it a tool? That’s the framework (we need).”

The 2025 Physicians AI report found physicians most commonly fear their employers will use AI for cost-cutting purposes, not care. Other major concerns are the inevitable liability they say AI will bring, and who will bear the legal responsibility for any patient harm related to its use; and the “loss of the art of medicine” — the combination of a medical practitioner’s gut instincts, their ability to recognize experience-based patterns, their overall assessment of a case, the wisdom to know when to act and when to watch, and human connection such as reading body language and building trust with their patients.

“We can feed artificial intelligence with all the information we want, but it’s not going to be able to have the emotional intelligence that a human being does … to truly know someone,” Dr. Frank Samarin, dermatologist at Mountaintop Dermatology, said in the fall.

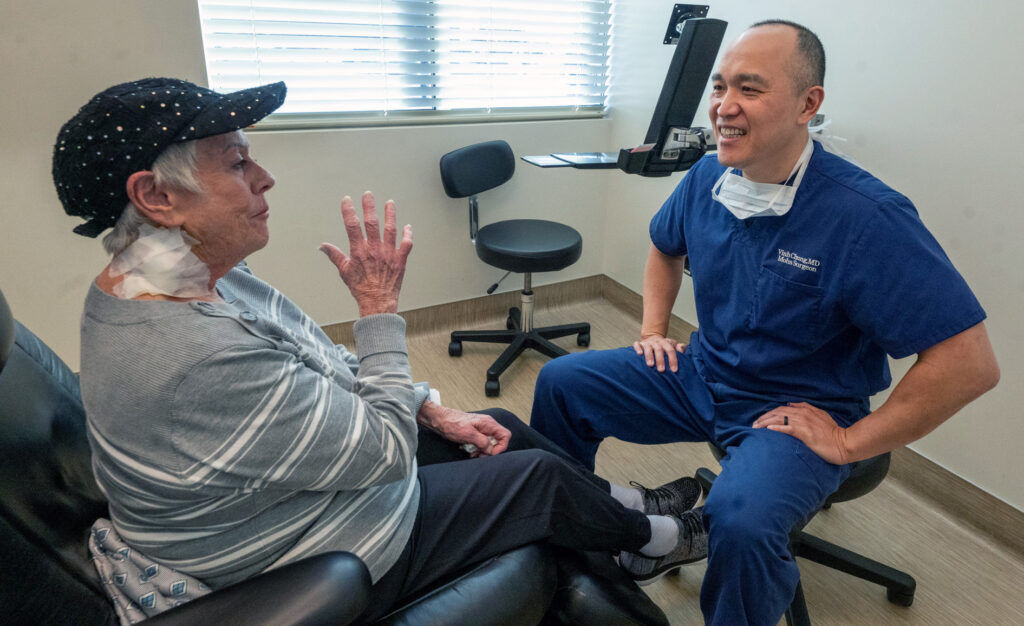

He was speaking over a cup of coffee with Chung and Dr. Deb Henderson, a dermatologist with the Skin Cancer & Dermatology Center. It was one of 100 coffee meetings that Chung committed to having with medical providers in the greater Colorado Springs area by the end of 2025. The initiative was Chung’s chosen way to fight isolation, which he believes could get worse with the rise of AI, and prioritize and build stronger connections within the local medical community.

“My concern with AI is that we’re substituting human connections with something that will distract you for hours and hours,” Chung said, noting AI’s use in professional settings and for personal entertainment.

Personal connection with their health care providers is important and necessary for patients because it offers a sense of dignity, the dermatologists agreed.

“I think, then, they don’t feel like just a number. And they probably feel seen and known,” Henderson said.

CommonSpirit Health primarily uses AI to enhance the human element of health care, by lightening the administrative burden for practitioners, Dr. Andrew French said in a recent interview. He is the president of physician enterprise for the health system’s greater Colorado and Kansas market.

“AI, just like it is in every other business and industry, is growing at a rapid pace. There are many opportunities to do many different things within health care, within clinical care,” French said. “We’re trying to be very intentional in selecting the tools that do things like decrease the cognitive load of our practitioners and making communication with our patients clearer. … And be thoughtful about how we roll those tools out, thoughtful of how we test them to ensure they’re going to do what we want them to do, in the way we want them to do it, before we sort of turn on a switch and use it ubiquitously throughout (CommonSpirit).”

Dr. Richard Zane, chief medical and innovation officer at UCHealth, said the health system is also focused on using AI responsibly to improve lives.

“Innovation is a strategic pillar for UCHealth, including the rational use of AI to improve lives by delivering superlative quality care and experience for our patients while enabling our employees to work at the top of their scope and substantively decrease administrative burden,” he said. “We make certain that the use of AI is safe, ethical and transparent and all of our policies, including the use of AI, require strict patient privacy and HIPAA compliance.”

It will always be necessary for humans to guide the ship, so to speak, medical experts agreed.

“For clinicians, nurses, doctors, advanced practice providers — in the end, this is still health care delivery. In the end, they are still the people who are making connections with patients. They are still the ones with the expertise … Ultimately, I think every physician, nurse and advanced practice provider understands their responsibility to the well-being and health of patients in our communities,” French said.

Vanguard Skin Specialists and the Skin Cancer & Dermatology Center use ChatGPT, an AI chatbot, in everyday settings, Chung and Henderson said. The Skin Cancer & Dermatology Center also uses an AI-powered patient messaging system.

Another common application of AI in medical settings is as a scribe, French said. CommonSpirit, UCHealth and Mountaintop Dermatology all use AI documentation and scribing tools; an AI scribing program UCHealth uses called Abridge also helps medical providers monitor their patients for sepsis.

Scribing tools have decreased the number of administrative tasks required of physicians and other care providers, improving their work-life balance, reducing burnout and improving the efficiency of care, said French, Samarin and Jill Collier, a primary care nurse practitioner at UCHealth.

“Rather than staring at a computer and furiously typing their notes and assessments, they can engage meaningfully with the patient. It allows us to pull the chair away from that computer terminal. It allows our physicians to sit with patients and have eye-to-eye, person-to-person conversations, connecting with them, to actively listen and empathize in a way they’ve never been able to before,” French said.

For Collier, medical AI including scribing programs, AI-powered medical search engines like Open Evidence, and general purpose chatbots like ChatGPT help her do her job more efficiently, allow her to create ultra-tailored patient care plans and give her more time with her patients.

She was one of 250 UCHealth providers who tested the Abridge program when the health system began piloting it last January. Today, nearly one-third of about 6,000 UCHealth doctors, nurse practitioners and physician assistance are using Abridge, the health system said.

“It gives me more intentional (time) with the patient. I feel more present,” Collier said of the scribing program and other AI-driven tools. “… Most people did not go into medicine because they want to spend all day on the computer.”

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the medical community to establish new ways to provide care, but virtual telehealth visits “were not a substitute” for traditional medical settings, Henderson said.

“I don’t think patients felt seen. They didn’t feel as well cared for,” she said.

Still, in the age of AI, Collier noted people don’t need to fear it.

“I think at this point, it’s not anything to fear. I think we all should have a healthy skepticism of AI and where it’s going, I think that’s safe. … The medical AI that I’ve seen, it’s not overreaching. I have not seen anything right now that gives me any sort of fear about where it’s transitioning to,” she said.

As AI continues evolving and its use becomes more prevalent, French underscored how health care organizations and providers must ensure human oversight remains in place.

“There are many different things AI could be used for in health care. That doesn’t mean all of them add a significant amount of value to the patients or the clinicians. The use of AI is about being selective in the tools you use, to provide the maximum benefit to the clinicians and to the patients while … allowing the clinicians and the health care experts to validate, drive and help design what the output of those tools will be — before utilizing them in the clinical space,” French said.