Ben Nighthorse Campbell was a Colorado original | Vince Bzdek

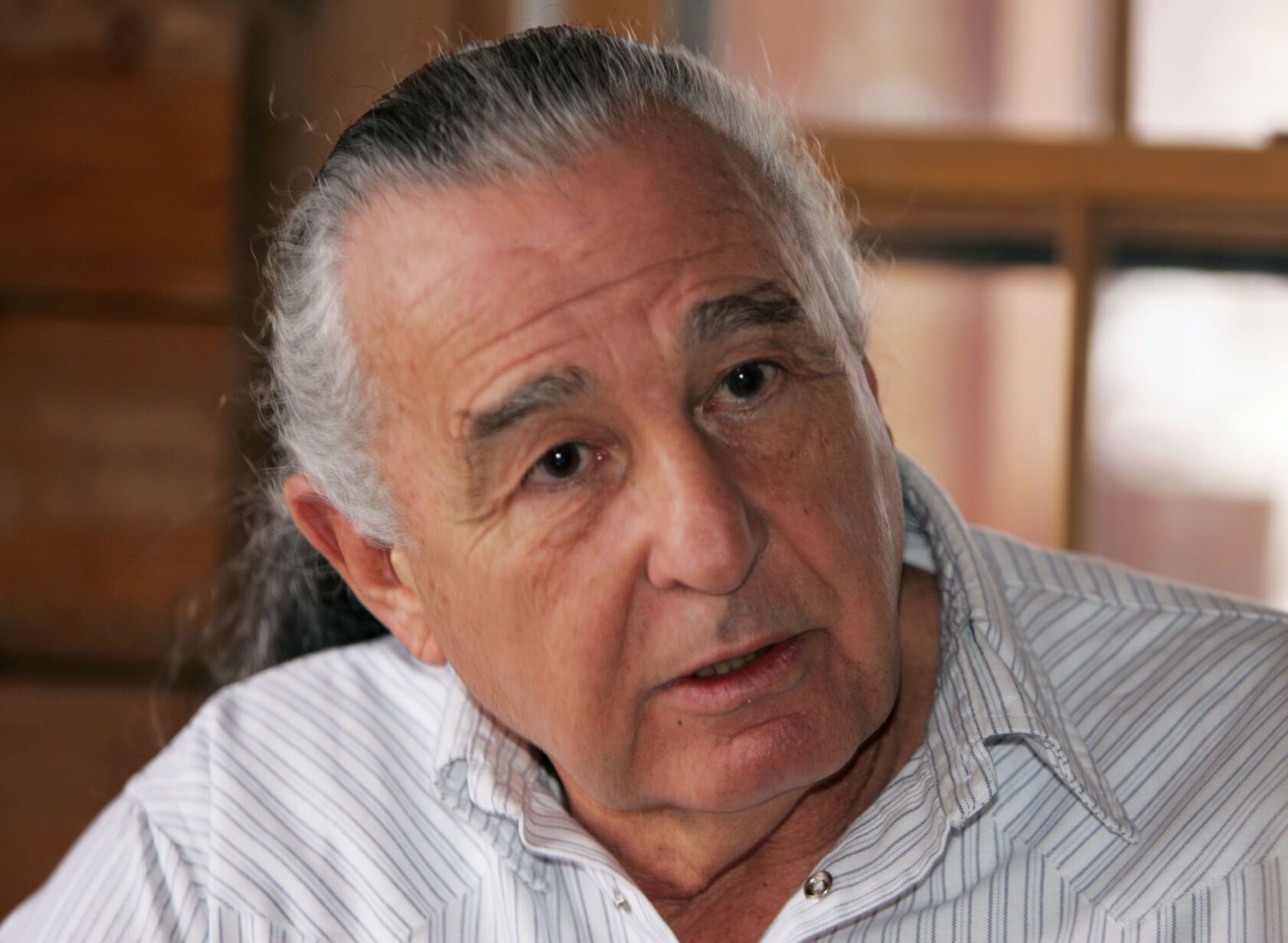

One day in 1982, Ben Nighthorse Campbell walked into a political caucus in Colorado to kill time after thunderstorms grounded his flight. He ended up volunteering to run for office that day and wound up serving two terms as a state legislator, three more in Congress and 12 years as a United States senator. Campbell, who died last week, was the only Native American serving in Congress at the time, leaving behind one of the most enduring permanent legacies of any Colorado politician ever.

That legacy includes places you’ve probably been to that were preserved by one of the most independent, original, groundbreaking politicians Colorado has ever produced.

Ever been to Black Canyon of Gunnison? Campbell made sure it became a national park, as he did with the Great Sand Dunes.

In the U.S. House, Campbell successfully co-sponsored legislation to rename the Custer Battlefield in Montana the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. The change, according to the National Park Service, was intended “to recognize indigenous perspectives” on the American Indian victory over Lt. Col. George A. Custer. Campbell was a descendant of Black Horse, a Cheyenne warrior who fought at the 1876 battle.

Perhaps his greatest achievement was the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. The remarkable limestone structure on the National Mall is the physical embodiment of a life and career spent championing Indian causes.

Campbell called the museum “a monument to the millions of Native people who died of sickness, slavery, starvation and war.”

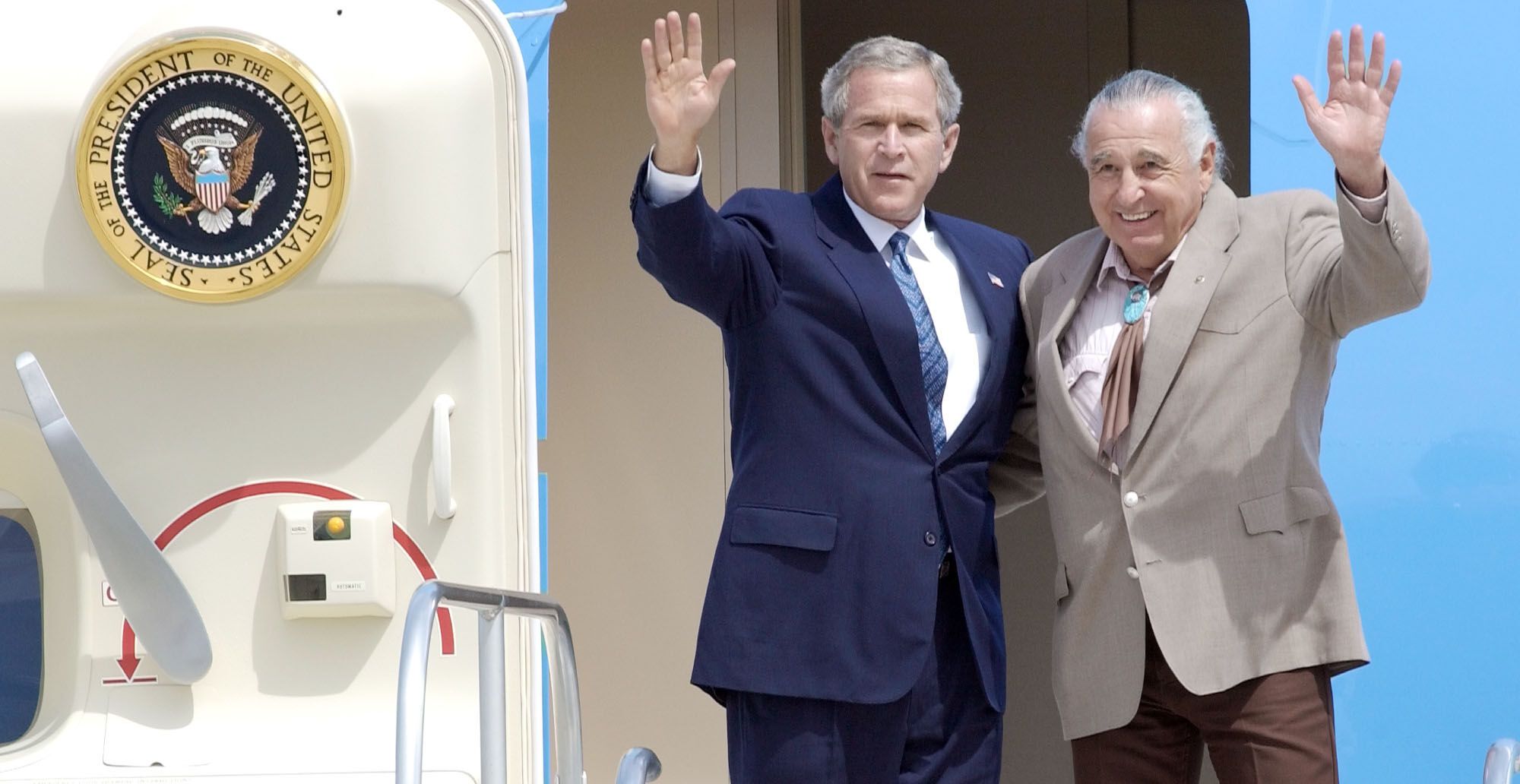

Wearing the full eagle feather headdress he had donned on the Senate floor as the sponsor of the museum bill, he led a parade of 25,000 Native Americans from more than 500 tribes through the streets of Washington in 2004 to christen the museum — the culmination of his lifelong efforts to protect sacred sites, strengthen tribal self-determination and improve health care, housing and education for Native peoples.

His involvement with the museum dated to 1989, when he was a sponsor of legislation that authorized construction of a building on the National Mall that required the Smithsonian to identify Indian remains and sacred objects in its vast collection and repatriate them to tribes requesting their return.

Unlike federal laws regarding water rights or tribal boundaries for Native Americans, the museum legislation “was about respecting their humanity,” Kristen Carpenter, director of the American Indian Law Program at the University of Colorado, told a journalist.

There is no other place like it on the Mall, just as there was no other politician quite like Campbell.

With its sinuous shape and ochre, light-catching limestone, the museum was designed to embody Native worldviews, not just house Native artifacts. From its rounded corners to its orientation facing East toward the rising sun, nearly every design choice reflects Indigenous relationships to land, time, and community. The building’s curving exterior and kiva-like lobby mirror forms shaped by wind and water — cliffs, mesas and riverbanks in the American Southwest.

Likewise, Campbell stood out as a unique, roughhewn product of the West, arriving at work on a motorcycle, wearing a ponytail and a bolo tie with a handmade silver and turquoise clasp. Irreverent, human and blunt, Campbell was a rancher, jewelry maker, Olympic judo champion and Air Force veteran. He was a fiscal conservative and a social liberal who favored gun rights and abortion rights. He switched allegiance from the Democrats to the Republicans in 1995.

Coloradans have a knack for embracing such outsiders who feel vivid and real to us, rather than suits, ideologues and cookie-cutter politics and politicians. Give us a red-blooded renegade rather than a pencil-necked paper pusher any day.

Jon Margolis of High Country News called Campbell the first postmodernist politician, skeptical of the grand narratives America tells itself, focused on the disenfranchised of either party, embracing complexity, irony, and the blending of contemporary, contrasting styles.

Without Campbell’s persistence, seniority and willingness to challenge institutional resistance, the National Museum of the American Indian likely would not exist in its current form — or on the National Mall at all. He is widely regarded as the museum’s architect in Congress. The design challenges the Western museum model, which often treats Indigenous cultures as objects of study. Instead, the NMAI’s architecture says the museum is part of the land and the community, shaped by Native values rather than those imposed upon them. The surrounding grounds are not decorative lawns but a Native landscape, with plants such as corn and sage historically used for food, medicine, and ceremony.

Unlike traditional museums that present cultures as static or “past,” the NMAI was designed for:

• Ceremonies

• Performances

• Contemporary Native voices

Campbell said it was a living museum, reinforcing the notion that Native nations are living, sovereign and modern.

The opening ceremony for the museum was one of the country’s most powerful moments of recognition for Native American history and culture.

Campbell’s personality and career are so wrapped up with the museum and its iconoclastic spirit that to many of us, he is this place. Put another way, Ben Nighthorse Campbell lives on in its walls.

At the end of the ceremony that capped his 15-year crusade to get the museum built, Campbell said it simply: “The circle is complete.”

Vince Bzdek, executive editor of The Gazette, Denver Gazette and Colorado Politics, writes a weekly news column that appears on Sunday.