Why do out-of-state donors have more power than in-state voters? | Vince Bzdek

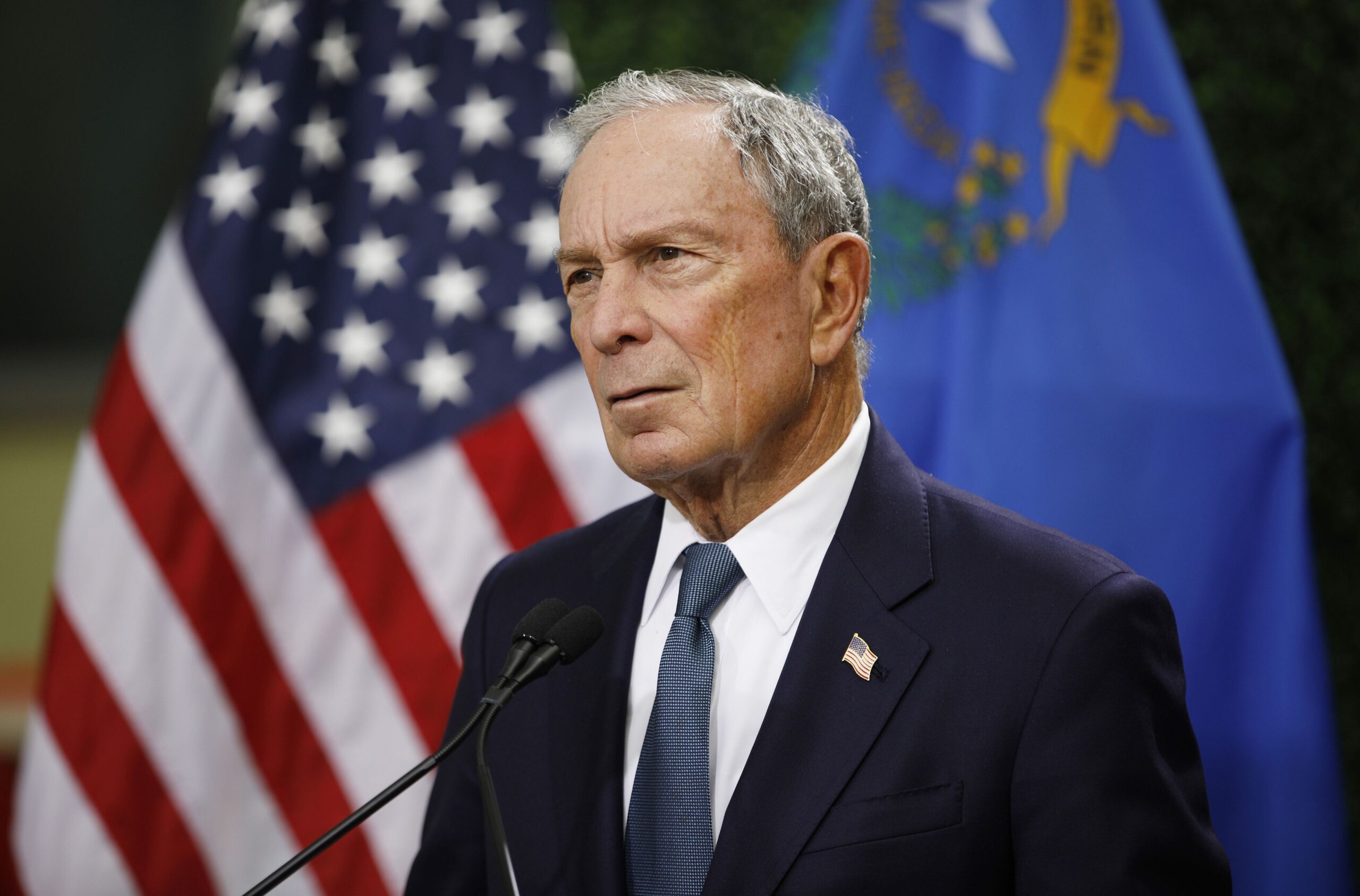

Why is Michael Bloomberg, the former presidential candidate, three-term New York mayor and founder of the financial info firm that bears his name, spending millions on Colorado elections?

The short answer: because he can.

The liberal New Yorker has donated $2.7 million to support Denver’s flavored tobacco ban, Referendum 301, to be decided on Tuesday. Two of his donations to that campaign were the largest individual contributions in Denver history, according to an Axios analysis.

Bloomberg is also the largest donor in the 2026 governor’s race, giving $500,000 to a super-PAC supporting U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet’s campaign.

“This is a very large donation for a statewide race,” Seth Masket, professor of political science at University of Denver, told me.

All told, Bloomberg has given about $10 million to Colorado political candidates and causes since 2012, including $500,000 for Denver Mayor Mike Johnston’s successful run for mayor in 2023 and $2 million for Johnston’s failed gubernatorial campaign in 2018.

He’s been an advocate for gun restrictions, charter schools and public health causes here.

Masket isn’t sure Colorado is an unusual target in this giving spree “because Bloomberg has been involved in lots of different ballot races and ballot initiative campaigns for years in lots of different parts of the country.” His giving in Colorado is consistent with his broader pattern of using his wealth to shape policy outcomes that align with his views.

“He often kind of flies under the radar, but he backs relatively progressive causes,” said Maskett.

Bloomberg does own a $44.8 million ranch and vacation home in Colorado, up north in Rio Blanco County. The 4,600-acre site called “Westlands” contains large areas for fishing and hunting, a four-hole golf course and a tennis court. So his interests in the state are not wholly that of an “outsider.”

But what may be more of a factor are the kinds of issues that are incubated here. Colorado has had a mix of battleground elections, initiative votes and policy fights over gun laws, tobacco and education reform that provide opportunities for him to influence policy areas he cares deeply about.

By donating in Colorado, Bloomberg is exerting influence at a state level that can have a ripple effect on national issues and help build networks of aligned policy makers.

So what’s the problem?

Well for one, large, outside donors like Bloomberg potentially overwhelm local voices, reducing their influence, and elevating national agendas in local contexts. And those national agendas are without question more divisive than local agendas generally are.

The unlimited spending power of political action committees — organizations formed specifically to raise or spend money to influence elections or public policy — has given disproportionate influence to the entities that can afford that spending, such as corporations, unions, and wealthy donors. This has been criticized for tilting the balance of power away from average voters.

Since the Citizens United decision in 2010 that ruled such contributions are a form of free speech, total outside spending on local elections has grown from approximately $144 million in 2008 to $4.2 billion in 2024.

Ironically, for individuals like you and me, Colorado’s campaign contribution limits are among the lowest in the country. For statewide offices like governor and state treasurer, the limit one person can give is $725 per election cycle. For state legislative offices, the limit is $225. For most local offices, the limit is $400 for individuals.

Conversely, the structure of Colorado’s political and ballot initiative system allows large donors to exert significant influence via super-PACS and advocacy campaigns.

There are no limits on how much individuals may give to a committee formed to support or oppose a ballot initiative in Colorado.

And political-action committees have no campaign contribution limits at all, though they cannot directly coordinate with candidates.

Corporations and labor unions cannot directly contribute to candidates or party committees, but they can make unlimited contributions to ballot measure campaigns.

That’s created this weird quirk in our democracy where a guy in New York has more power to influence the future of Colorado than the voters in the state who live here. Colorado can limit its own voters to giving a few hundred dollars to candidates but somehow cannot limit out-of-state donors from giving billions to help elect candidates here.

Other states such as Alaska, South Dakota and Vermont have tried to limit the influence of non-residents, but federal courts have all struck them down as violating the First Amendment’s protections for free speech.

Hawaii has been unique in its ability to restrict out-of-state money, which is capped at 30% of the total money a candidate can spend.

But Masket points out that money isn’t everything in Colorado elections.

Businessman Kent Thiry gave $3.2 million to the effort to pass ranked choice voting across the state last year. All told, $15 million was raised to pass the effort. It failed big time.

In 2016, a ballot measure to hike tobacco taxes raised more than $34 million. The measure failed by 6 percentage points.

Colorado is just ornery enough that it will often vote against the biggest money raisers in elections, worried that they are trying to buy elections out from under voters.

In that vein, Masket cautions against reading too much into the Bloomberg donations to Bennet this early on. His chief rival, Attorney General Phil Weiser, has still raised more money than Bennet so far.

“I mean, to some extent, large cash infusions late in elections tend to be way overhyped,” Masket said. “At this point, this is pretty early. We’re still a year out. This is something that, you know, a lot of Coloradans have not paid a ton of attention to yet.”

At this stage, Masket sees some benefits to Bloomberg’s bucks.

“People have a lot of information that they still need, and this is how they get it,” he notes. “They’re going to get it from TV ads and yard signs and leaflets and all sorts of other campaign activity.” All that outside money helps pay for those education efforts.

Later in the campaign, as the primary approaches in June, we’ll see outside money become a campaign issue.

“It’s fairly often that the candidate that has done better, the candidate who has raised more money, is often criticized for taking in a lot of out-of-state money,” Masket observed. “That’s a reliable campaign issue, just because voters are leery of big money to begin with. They’re especially leery of money that comes from outside the state. What’s not clear to me is that outside money actually hurts anyone when it comes to voting.”

“Bennet will have to come up with at least some sort of an explanation about why this isn’t harmful, why this still allows him to serve people in Colorado well,” Masket adds. “I don’t know how many votes it’ll switch, but it’ll be an issue.”

Colorado could do much more than it does to track and restrict the influence of outside money like Bloomberg is giving than it does. The state could:

- Require real-time disclosure of money in elections, especially large contributions and independent expenditures so people know more quickly where the money is coming from. There is already a requirement for reports of contributions of $1,000 or more within 30 days of an election. What if any independent expenditure above, say, $10,000 had to list major donors within 24-48 hours, so folks who vote early by mail know who is paying for what?

- Bring light to dark money. Out-of-state money often hides behind “dark money” shell companies or pass-throughs. Colorado could require more detailed disclosures from all out-of-state, foreign or shell companies, and make it clear who the real donor is, what their state of residence is, and whether the donations are from prohibited sources.

- Adopt enhanced disclosure rules or triggered scrutiny for out-of-state funds. For example, if more than 50% of a committee’s funding comes from out of state, require immediate disclosure of the sources of those funds and put caps on percentages of funds candidates can get from out of state, which might just past muster with federal law.

- Expand public financing of campaigns or small donor matching programs to dilute large out-of-state and large donor influence. Denver tried public financing a couple years ago with mixed results, so the jury is still out on this option.

Reforms may be a-coming. I’ve seen one proposal for a Colorado Campaign Finance Transparency & Accountability Act that requires real-time disclosure of any contribution over $200, a ban on donations from corporations with more than 5% foreign ownership, and a requirement that dark-money groups must report their funding sources publicly before making expenditures in Colorado elections.

The possible 2026 bill or ballot initiative also toughens up enforcement and fines for violations of campaign finance rules.

“Honestly, it wouldn’t surprise me to see some sort of campaign finance initiative statewide in the near future,” Masket said to me. “There tends to be a pretty strong backing of what you might call good government initiatives here in Colorado.”

He cites recent popular initiatives such as the state’s pioneering redistricting reforms and the vote-by-mail initiative, which Colorado led the way on nationally.

It’ll be interesting to see how little Bloomberg contributes to the campaign for that law.