Colorado hospitals are operating on ‘unsustainable’ margins, report finds

Nearly 70% of Colorado hospitals ended 2024 with “unsustainable” margins, according to a new financial report from the Colorado Hospital Association.

Tom Rennell, the group’s senior vice president of financial policy and data analytics, said hospitals’ expenses are outpacing their revenue, as an increasing number of Colorado patients are losing their insurance coverage, partially due to the post-pandemic Medicaid unwind.

“Over the last several years since the COVID times and through the high inflationary times, hospitals have been experiencing some significant econmic turbulence,” Rennell said. “We don’t have the full picture yet, but I can tell you that what we’re seeing so far in 2025 is that there has been even more of a deterioration as expenses are up higher than revenue.”

The report said rural hospitals have it even worse: More than 80% were unable to achieve sustainable margins, a 12-point increase since 2019.

Given the hospitals’ fiscal predicament, the association said policymakers should review Colorado’s regulatory structure to shed laws or rules that are unnecessary.

“In this era where resources are so constrained, I think we would say, ‘Let’s look at some of the policies that have been put in place and some of the regulations that have been put in place and see if those don’t need to be in place anymore, whether they’re more administrative or they’re not leading to patient care improvements,'” he said.

The association’s report said hospital expenses went up by 52% since 2019, while revenue only increased by 39%.

Financial instability has led many health care facilities in the state to take drastic measures, such as cutting certain programs and services and conducting mass layoffs, according to the report. While none of the state’s acute care facilities has had to close its doors as a result of financial hardship, three behavioral health centers — West Springs Hospital in Grand Junction, Johnstown Heights Behavioral Health in Johnstown, and West Pines Behavioral Health in Wheat Ridge — all shut down last spring, leaving about 500 behavioral health professionals out of a job.

Rennell said a combination of factors, including the Medicaid unwind, an increase in immigrants arriving in Colorado in early 2024 after illegally crossing the southern border, and growth in the state’s Hospital Discounted Care program have led to a 123% increase in “charity” care since 2021.

Charity care, also known as “uncompensated care,” refers to medical services provided free of cost to patients.

While the unwind led to some 500,000 Coloradans losing Medicaid coverage, Medicaid and Medicare still saw a significant increase in enrollment in recent years, Rennell said, due in part to Colorado’s aging population. The two programs make up over 60% of hospital coverage, according to the association’s report.

However, reimbursements were nearly $4 billion short last year, a $385 million increase from 2023, the report said.

“In some cases, if you don’t get paid at cost or you lose money on Medicaid or Medicare, maybe you could charge a little bit more on commercial and try to make some of that up for the private payers, but a lot of hospitals can’t do that; they aren’t able to negotiate with the private carriers,” he said.

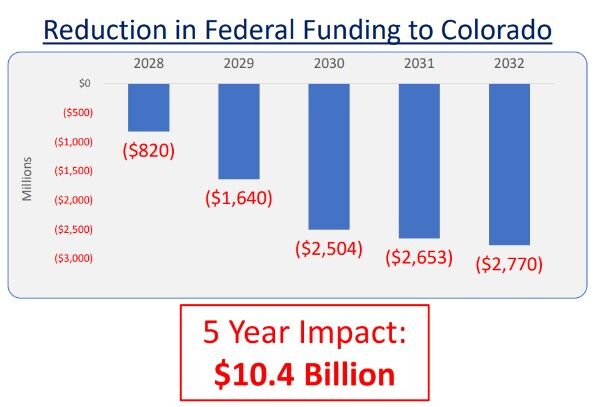

The number of uninsured patients is only going to increase in 2026, as the federal budget bill known as HR 1 takes effect, according to the association. The congressional budget cuts more than $10 billion from Colorado hospitals over the next five years, said Rennell, who estimated that more than 100,000 Coloradans will lose Medicaid coverage.

“People will lose coverage and will try to access care wherever they can, hospitals will step up and provide that care to anyone who walks in and needs that care, of course we will,” Rennell said. “But in the midst of shrinking reimbursements and people losing coverage, it’s just something we haven’t seen before, and I think the entire health care system is going to have some really significant challenges ahead of us.”

Medicaid costs have been rising in the last several years under the Affordable Care Act, particularly after 40 states, including Colorado, and Washington D.C. expanded Medicaid eligibility.

Critics of the expansion said changes are long overdue to address the rising costs and ensure the program’s long-term sustainability. In particular, they noted that the federal government has paid for a bigger and bigger share of Medicaid expenses, with the “Obamacare” expansion responsible for much of that shift. The new categories of eligible enrollees had received a much higher federal reimbursement rate.

Republicans in Colorado and elsewhere have defended the changes adopted in the congressional budget, saying fraud, waste, and abuse exist in the system and the new work requirements to maintain eligibility, among other things, would ensure that Medicaid is available for the vulnerable populations who need it most.

Supporters of the expansion said it enrolled millions of Americans, ensuring they have health care. They argued that rolling the program back would have grave ramifications, including uninsured people showing up in emergency rooms and increasing hospital costs.

HR 1, the congressional budget, imposes the work requirements for Medicaid recipients starting in 2027, phases provider fees down from 6% to 3.5%, and freezes existing provider fee programs.

While the legislature reversed a planned provider rate increase during a special session in August, the state hasn’t been able to do much else to help the health care industry prepare for what’s to come, Rennell said, because it’s too busy dealing with the budget deficit.

“As the impact of HR 1 comes into play, the state is already having challenges, and I think longer-term that the challenges to our health care industry, and to the Medicaid program a little bit more specifically, are going to mount and get bigger and bigger,” he said.