Colorado’s recidivism rate has decreased significantly, but violent crime is up, new analysis finds

Changes to Colorado’s crime policies led to a significant decrease in recidivism in the state’s prisons, but lowering penalties for certain offenses also increased the number of violent crimes, according to a new analysis.

In its report “The Reform Paradox: How Reduced Incarceration has Coincided with Rising Crime,” former Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen, along with DJ Summers and Emma Roberts, highlighted a trend over the past 15 years in which they said state lawmakers increasingly “prioritized leniency” in sentencing by lowering sentences for drug offenses and expanding access to parole and probation.

“These measures were intended to correct excesses of the past and emphasize rehabilitation over retribution,” the authors of the Common Sense Institute (CSI) report wrote. “This is a noble goal, in keeping with Colorado’s dedication towards justice in all aspects.”

However, they argued, “a functional criminal justice system must serve two ends: justice for offenders and justice for victims.”

Some of Colorado’s recent reforms have placed “disproportionate weight” on the treatment of the offender, rather than focusing on victims, the authors contended. When this happens, “the balance of justice falters, and the law-abiding public bears the cost not just to their own property and bodies but to their state’s economic well-being,” they added.

Supporters of the policy changes have argued that simply incarcerating people hasn’t worked for Colorado — that it merely entrenches criminal behavior, even as the costs continue to rise. They have argued that diversion and other programs are much less expensive and more effective.

Instead of expanding jail beds or keeping inmates longer, the state should focus on behavioral health and other services, as well as investments in poor areas in order to provide more economic opportunity, they said.

Colorado’s recidivism rates see sharp declines

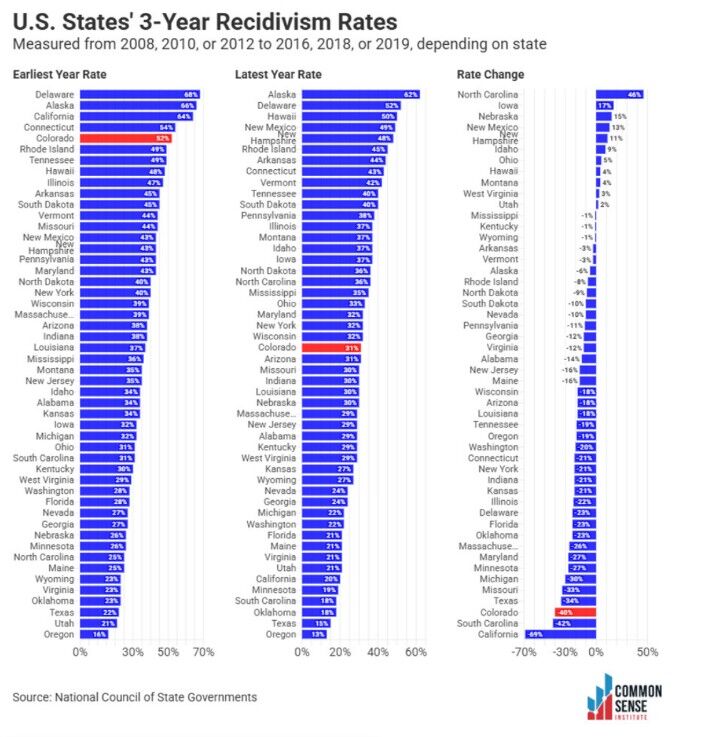

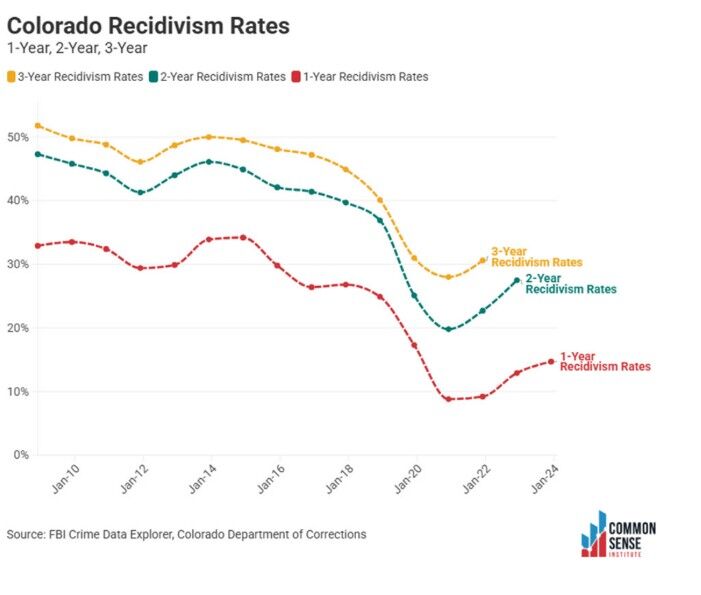

Colorado’s recidivism rate fell by 40% from 2008 to 2019, the third-highest drop in the U.S. In that same period, the number of inmates who returned to prison within three years fell by 20%, while the total number of Department of Corrections inmates decreased by 12% from 2016 to 2024.

The report attributed the state’s declining recidivism rate partially due to several pieces of legislation that went into effect over the past decade, including the following:

- Senate Bill 15-124, which requires parole officers to use “intermediate sanctions” like short-term jail stays or placement in treatment programs before revoking parole when an individual has committed a technical violation.

- Senate Bill 19-143, which limits parole revocations for technical violations by requiring non-criminal violations to be addressed with “graduated” sanctions, such as warnings, more frequent drug testing or curfew.

In the authors’ view, the measure that could most impact Colorado’s rate in the future is Senate Bill 030, which established a working group to develop a new definition of recidivism in 2024. Under the new definition, which took effect on July 1 of this year, recidivism only applies to felony or misdemeanor offenses, not probation or parole violations.

Former Arapahoe County District Attorney John Kellner, a Republican who is now a fellow at the Common Sense Institute, said the narrowed definition and the resulting drop in recidivism rate “masks what’s really going on” with crime in Colorado.

“This recidivism reduction is a phantom reduction in many ways,” since it doesn’t cover parole and probation violations, Kellner said. “It’s masking a true problem.”

Arrests down, violent crime up

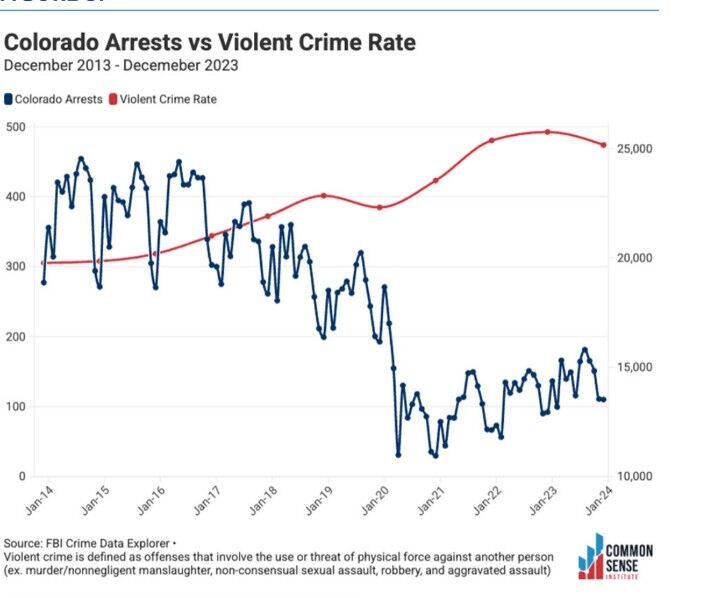

While arrests have decreased by about 40% over the past decade, violent crime has increased by 55%.

“It’s very disturbing to me,” said Mitchell Morrisey, who served as Denver’s District Attorney in the early 2000s.

The CSI analysis found a direct correlation between arrests and violent crime rates, which, for Morrissey, demonstrates that “when you’re not arresting violent criminals, the violent crime rate goes up.”

Morrissey said he believes the increase in violent crimes, such as aggravated assault, as well as property crimes like auto theft, is an unintended consequence of several laws passed in the state over the last decade or so.

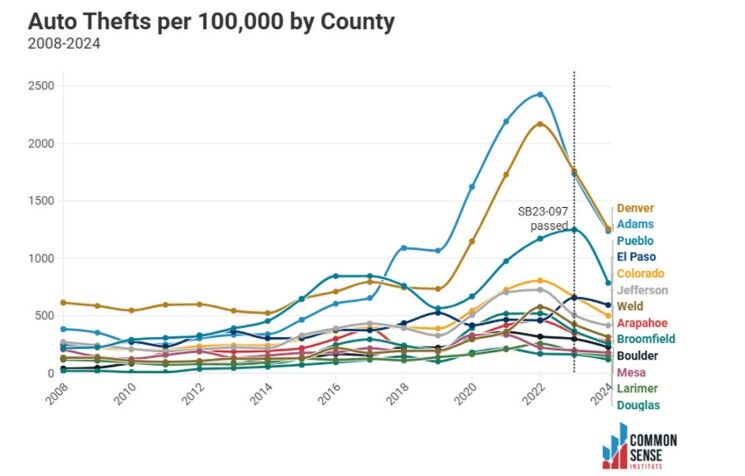

The analysis noted that the legislature has reversed some of those laws, mentioning 2023’s Senate Bill 097, which made vehicle theft a felony regardless of a car’s value. Lawmakers passed the law at the urging of Gov. Jared Polis following a rise in motor vehicle thefts in the state, which reached an all-time high in 2022.

Following the bill’s passage, auto thefts decreased significantly. Many attributed that drop to the new law.

Colorado lawmakers have amended laws in response to surges in crimes or deaths, such as three years ago, when the legislature amended a 2019 statute that reduced the charges for possession of up to 4 grams of schedule II drugs, which includes fentanyl, from a felony to a misdemeanor.

The legislature took that action after fentanyl overdose rates spiked.

Unintended consequences

The authors of the CSI analysis said Colorado legislators should examine some of the changes in criminal law they have passed in the past two decades to determine whether there may be unintended consequences.

In particular, they mentioned two bills they believed should be amended:

- House Bill 20-1019, which made it a misdemeanor for an individual to leave a residential treatment facility without permission. The authors of the analysis argued that the offense should be a felony, rather than a misdemeanor.

- Senate Bill 20-217, which, among other provisions, limited qualified immunity for law enforcement officers.

“The absence of qualified immunity may prevent officers from taking the necessary actions to defend life and property,” they wrote. “Legislators should reinstate qualified immunity and examine the impacts of other aspects of the act.”

The sponsors and supporters of those policies have defended them as the right course for Colorado.

Referring to the bill that created the recidivism working group, Rep. Matthew Martinez, D-Monte Vista, said agencies throughout Colorado have adopted varying definitions for recidivism, making it more difficult to use as a data point when drafting legislation to address public safety issues.

“We’re streamlining the definition across Colorado agencies to make ‘recidivism’ a useful tool in policy-making and continued evaluation of our justice system to create a safer Colorado,” he said then.

Others view some crime laws as part of an “unjust” regime.

“This is not a new issue,” then-Rep. Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez, now a Denver councilmember, said during a committee hearing on SB 20-217. “I am a third-generation resident of Denver and six generations in Colorado. And I can tell you that my parents and my grandparents have been fighting these injustices before I was born.”