Colorado Supreme Court walks back decision allowing localities to broadly permit violations of noise limits

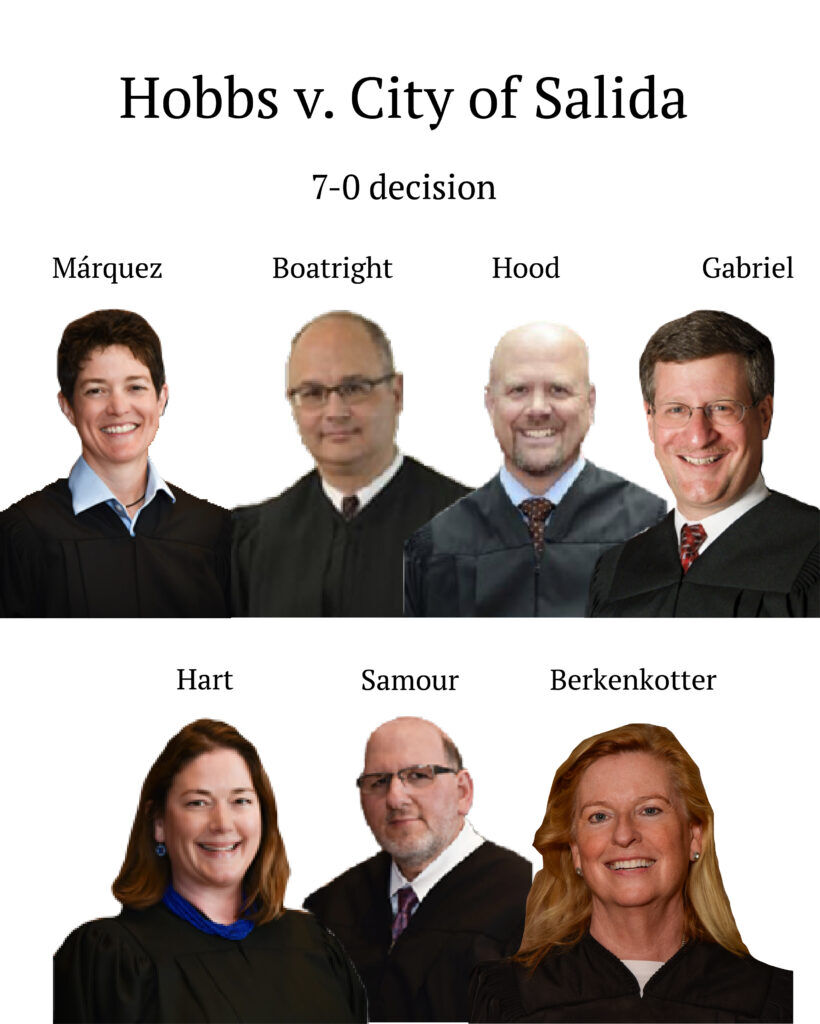

The Colorado Supreme Court concluded on Monday that the state’s noise pollution law does not allow local governments to categorically permit any entity to host events on private property that exceed the statewide decibel limits.

The question had divided the state’s Court of Appeals, with one appellate panel deciding localities do have broad permitting power for private property, and another deciding months later that they do not.

Breaking the tie, the Supreme Court acknowledged the language of the law was ambiguous. But taking account of lawmakers’ stated goals, the justices concluded the legislature intended to allow local governments, on property they use, to permit others to exceed statewide noise limits for cultural or entertainment events.

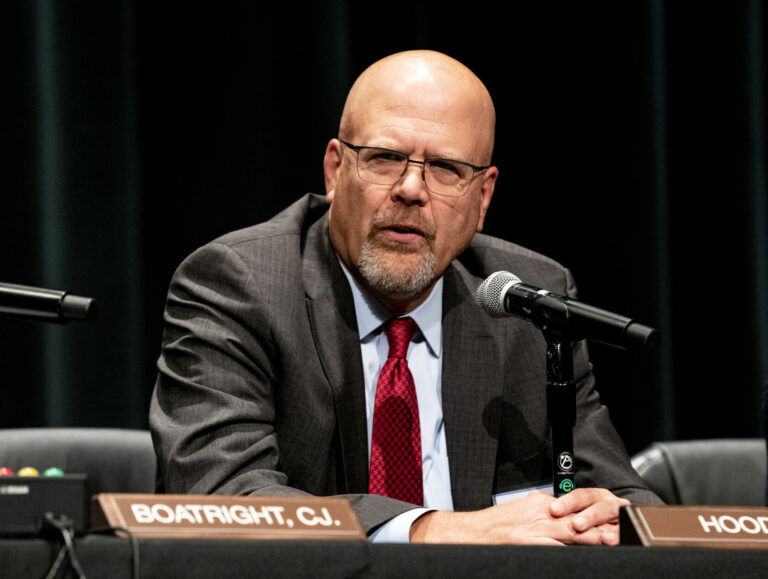

“No one suggested that the exemption would allow a for-profit entity to host an event on private property not used by” the government, wrote Justice William W. Hood III in the Sept. 8 opinion.

Colorado’s Noise Abatement Act sets decibel limits for classifications of property. However, lawmakers enacted a 1987 amendment jokingly named the “Fiddler’s Green bill” — a reference to the Greenwood Village amphitheater that would open the following year. The amendment rendered the Noise Abatement Act’s limits inapplicable to the “use of property by” the government, nonprofits, or their “licensees” and “permittees” when holding concerts and music festivals. The change also clarified that local governments retain the authority “to regulate noise abatement.”

More than three decades later, it was unclear to the Court of Appeals which entities, exactly, were eligible to exceed the decibel limits pursuant to a permit. The wording of the law suggested multiple potential outcomes:

• Any property could exceed the state decibel limits if used by the state, local governments, nonprofits or entities that receive a license, lease or permit for cultural events; or

• Any property used by the state, local governments or nonprofits for cultural events could exceed the decibel limits — with entities that receive a related license or permit from them included in that exemption

One Court of Appeals panel decided in March 2024 that localities do have broad permitting power for private property not used by the government. In that case, attorney Matthew Hobbs sued Salida for authorizing the nearby High Side! Bar & Grill to hold summer concerts with noise levels exceeding the state caps.

By 2-1, the panel believed the law was intended to give local governments flexibility to regulate cultural and entertainment events, with objectors able to voice their concerns to city officials.

“The fact that such a remedy does not always lead to the particular result desired by a particular party does not mean that the statute, or the political process that it contemplates, is absurd,” wrote Judge Timothy J. Schutz for the majority.

Judge Jerry N. Jones argued in dissent that the 1987 exemption for cultural events only applied to land used by governments or nonprofits. There was “nary a mention during any hearing on or reading of the bill of potential applicability to private property not owned by a not-for-profit entity, such as High Side,” he wrote.

Three months later, a different appellate panel concluded, like Jones, that local governments cannot provide exemptions for land used exclusively by for-profit entities in a case also out of Chaffee County.

“Had Salida done a contract with High Side! to do an event in Salida’s name — ‘We’re gonna put on a Celebrate Salida Day and we’ll do it at High Side!’ — that would be OK in your view?” asked Justice Richard L. Gabriel during oral arguments in Hobbs’ appeal.

Correct, said attorney Julian R. Ellis Jr., because the city would “take ownership of” the excessive noise.

“By requiring the municipality, the state, to be involved in these events, you’re taking resources from these smaller communities,” argued attorney Erica Romberg for Salida. “The staff resources, the time of the people.”

The Colorado Municipal League also weighed in on behalf of Salida, contending the Supreme Court should not “undermine reasonable local regulation” that allows communities to permit cultural or entertainment events.

“It seems to me it doesn’t have to be such an awful outcome. It just means events have to occur at lower decibel levels and arguably everyone’s a winner,” noted Hood during the arguments.

Ultimately, the court believed that the more expansive view of the Noise Abatement Act would “exempt a far larger swath of the population” from decibel limits than lawmakers intended.

“High Side’s concerts weren’t held on property used by the City for a statutorily authorized purpose, so Salida didn’t have the authority,” concluded Hood, “to issue amplified sound permits to excuse High Side’s NAA’s violations.”

Attorneys for the city and for Hobbs did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

“Honestly, we were pretty surprised because the language in the statute seems pretty clear and there hasn’t been a dispute about the language for decades,” said Kevin Bommer, executive director of the Colorado Municipal League. “We’re concerned and hope it doesn’t have an impact on the vibrant downtowns and venues that you find all across Colorado.”

The case is Hobbs v. City of Salida et al.