Denver parents denied ‘fundamentally fair’ child neglect proceeding, appeals court finds

Colorado’s second-highest court agreed last month that two Denver parents were denied a “fundamentally fair proceeding” in their child neglect case when the city imposed new conditions and a judge approved them without hearing from the parents first.

In July 2022, Denver Human Services initiated a child neglect case against a mother and father. A judge deemed their two children neglected and adopted a treatment plan for the parents. The children, in turn, went to live with relatives in New York.

In 2024, the department sought to terminate the parents’ legal relationship with their children, but the parties quickly reached a preliminary agreement about custody that stopped short of termination. The department’s written motion indicated the children would remain with the New York relatives until they were adults and the parents would not seek for the children to be placed elsewhere during that time.

At a July 2024 hearing, the department asked Juvenile Court Judge Lisa Gomez to sign the corresponding custody order. However, the order did not include the conditions requiring the parents to allow their children to remain with relatives until they turned 18. Attorneys for Denver and the parents agreed that the order as presented reflected the agreement of the parties. Gomez approved the order.

Shortly afterward, the department filed an amended version of the order, noting the purpose was to add terms that were “missing” from the order Gomez approved. Specifically, the amendment restored the prohibition on the parents attempting to change the children’s custody as long as they were minors.

Gomez signed off on the amended order one day later, without seeking the parents’ response.

A three-judge Court of Appeals panel agreed with the parents that the unilateral modification of the custody order violated the procedural rules and denied the parents a “fundamentally fair proceeding.”

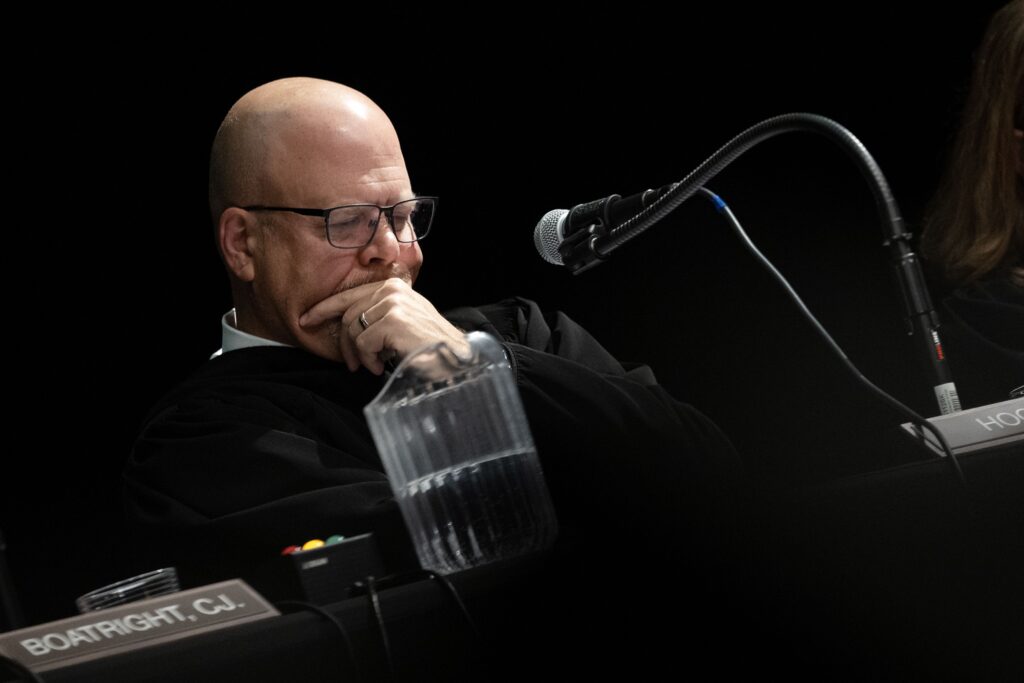

Judge Daniel M. Taubman, writing in the March 13 opinion, noted that even if the panel were to accept the city’s argument that its amendment sought to correct a “clerical error,” Denver still did not follow the proper protocols for doing so.

“As a result, the juvenile court was not alerted to the parents’ opposition to the proposed amended (custody) order. Because the court apparently believed that the parents agreed with the amendment, it did not provide them with a chance to respond,” wrote Taubman, a retired judge who sat on the panel at the chief justice’s assignment.

He concluded that the parents’ inability to contest the new restrictions required a reversal of the order.

“We also conclude that the parents suffered prejudice from the juvenile court’s error,” Taubman added, “because the additional terms prohibited them from ever asking a court to change the children’s placement.”

The case is People in the Interest of R.Q.S. et al.