Is Colorado becoming more secretive? Lawmakers say no, critics say yes

Are Colorado lawmakers making it difficult for the public and the media to access public records or figure out what policymakers are up to?

Sponsors of several bills insist the answer is no.

Others question the path the Democratic-led state legislature appears to have carved in the last few years. They said lawmakers have pushed and passed laws that make public records less accessible and which chip away at transparency.

Jeff Roberts, the executive director of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, said it’s not just about accessing public records that worries him — it’s also about new policy to exempt state lawmakers from open meeting laws.

Lawmakers, meanwhile, insist that the laws and a slew of new proposals would make accessing public records more practicable for government custodians. They also argue that, before they changed the open meetings law, it was unworkable.

An exemption for legislators only

Roberts referred to last year’s law, which the Democratic majority passed to exempt the legislature from parts of the Open Meetings Law. The lawmakers took that action after a judge ruled they had violated the law. Two House Democrats had sued over other violations of the open meetings law, including the use of secretive electronic messaging services and caucus meetings held without public notice or minutes.

The exemption for lawmakers went into effect on the same day that Gov. Jared Polis signed the bill, which put limits on what constitutes “public business” and allowed lawmakers to discuss bills and public policy via email or text message without it being subject to the open meetings law. Those communications could be available through an open records request — so long as the person making the records knows who was in a conversation and when it took place.

Critics said lawmakers applied that exemption during last year’s special session to tackle property taxes. Lawmakers blocked reporters and the public from attending caucus meetings and the deal was reached behind closed doors without public review or scrutiny, critics said.

At the time, House Speaker Julie McCluskie said the meetings weren’t public because they weren’t voting on proposed legislation. Senate President James Coleman did not respond to Colorado Politics’ request for comment.

Longtime Colorado journalist Sandra Fish, who is now semi-retired from the Colorado Sun, said “it’s very disappointing” to see the trend of blocking the media and public from caucus meetings, where, she noted, the policy decisions are made.

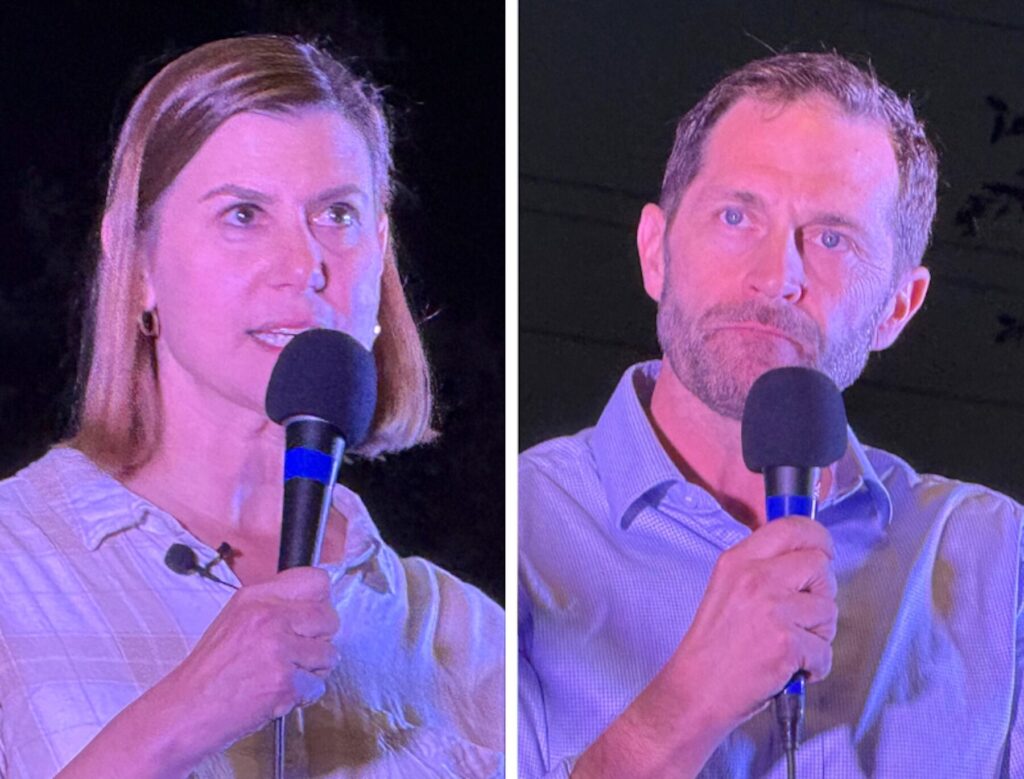

This year, House Bill 1242, sponsored by Sen. Byron Pelton, R-Sterling, and Rep. Lori Garcia Sander, R-Eaton, aimed to repeal the 2024 law and require state lawmakers to conduct business entirely in the open. Democrats killed the bill in committee in a party-line vote.

Garcia Sander argued that under the 2024 law, public hearings would become nothing more than a formality, eroding public trust.

Other lawmakers defended the legislature’s actions.

“Every action I take as an action in this building is public,”said Rep. Chad Clifford, D-Littleton. “Almost every dialogue that I have that matters is in a committee room, just like this one on a mic where you can go back and listen and get the transcript. And 100% of every vote I have ever taken in this building is recorded in a journal. There’s very little that the legislature does in private.”

Lawmakers: Agencies need more time

Roberts said several bills this year are worrisome because they further limit people’s rights to access records and add barriers to the people’s right to know.

“Overall, there appears to be a trend towards relieving the burdens on the government and records custodians at the expense of the ability to access public records, and that’s disappointing,” Roberts said. “I think as far as these are concerned, both the news media and the public are pretty powerless to do much about it.”

Senate Bill 77 would extend deadlines for public records custodians to fulfill requests from three days to five and even longer in “extenuating circumstances,” which is not clearly defined. This is the second attempt to pass the measure after it failed last year.

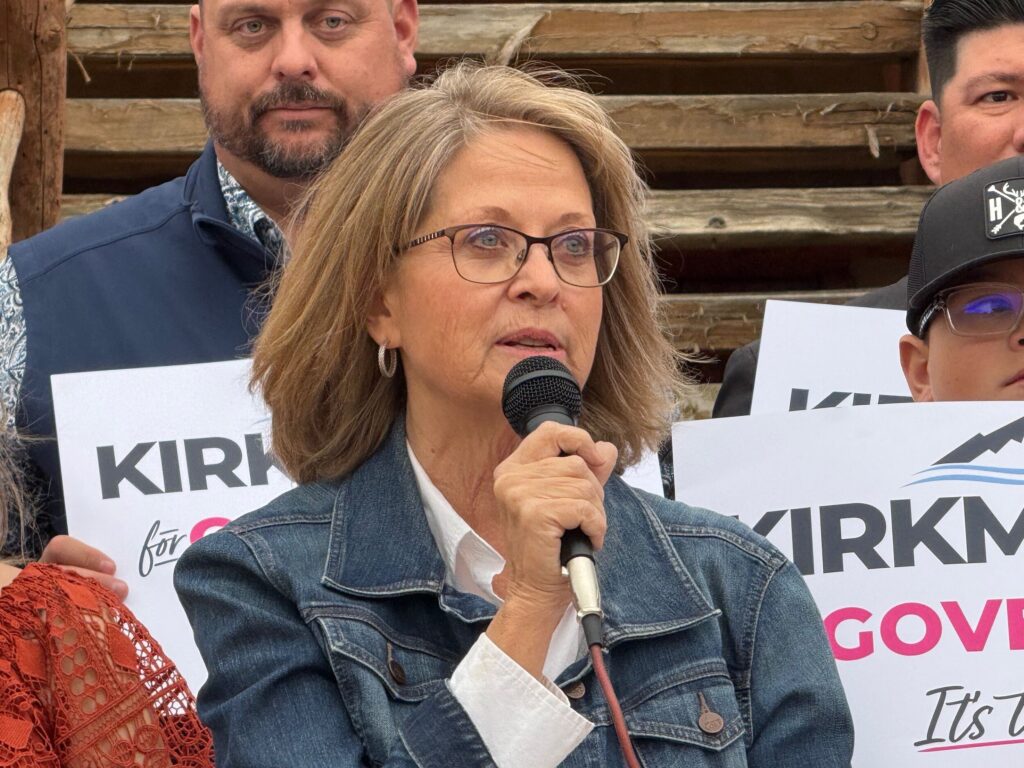

Sen. Cathy Kipp, D-Fort Collins, who is sponsoring SB 77, told Colorado Politics that government agencies need more time because the number of requests they receive from the media and the public is increasing exponentially.

Kipp said the trend is only getting worse, dating back to the COVID years. Some agencies, she said, have seen more than 300% increases in requests.

“We’re just feeling like there needs a little bit of reprieve in order to do this,” she said. “As I have said, the bill is just really trying to be fair and balanced.”

During committee hearings, Jefferson County’s Karen Wick, a proponent of SB 77, said the number of CORA requests has increased each year.

In 2019, Wick said the county saw 217 CORA requests. Last year, it climbed to 650, she said, adding the requests are getting more complex and time-consuming.

The Colorado Municipal League’s Heather Stauffer also spoke in favor of the bill’s time extension, which she said acknowledges the “operational realities” faced by those in charge of public records. She questioned the value of creating two tiers of requestors — requests from the media must still be filled in three days under the bill. Stauffer said the media should be treated the same way as the public.

Advocate: Why not post information online?

Roberts countered that government entities could save time and decrease the number of CORA requests by posting common questions and other information online.

“They should be keeping track of what the public is interested in knowing about government and doing the best they can to make a lot of that information available,” Roberts said. “Financial information is something that a lot of people are interested in. And there was testimony that much of this is no longer available.”

A 2021 law that went into effect in 2024 sought to increase access for Coloradans with hearing and vision impairments by requiring online, public access. When counties and entities couldn’t meet the disability requirements, many completely pulled public records altogether from online access, fearing they might violate the law.

When pressed if SB 77 yet prevents the public from obtaining public records, Kipp said, “No.”

“I think that we should be as transparent as possible but still allow us to get our work done,” she said.

While the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition has taken an amend position on SB 77, Roberts said the accountability factor is a major issue that state lawmakers have not addressed. Notably, he said, there are little to no consequences for government agencies that fail to meet deadlines.

In one case, Roberts said, a requestor took the matter to court, where judges ruled that, even though public records custodians ignored deadlines, there was no fault because they were eventually delivered months later.

The cost of obtaining public information is increasing

Passed into law in 1969, the Colorado Open Records Act ensures that all public records are open for inspection by any person at reasonable times, unless a record has been specifically made not public by law.

It has become more and more expensive for citizens to get those records, according to Roberts and others.

Barriers already exists due to the exorbitant fees being charged for public records, Roberts said.

In 2014, the state passed a bill allowing “inflationary” factors to be built into fulfilling public records requests. Fees in Colorado currently stand at $41.37 an hour.

The Colorado Attorney General’s Office, for example, is now charging the maximum at $41.37 per hour. Around 340 governments in the state have also raised their rates to the max since the new rate was implemented on July 1, 2024, according to Roberts.

Kipp defended SB 77, saying the first hour is free.

“And that rate can be multiplied by however many hours the government says it takes to fulfill your request,” Roberts countered.

In March, Jefferson County said it would cost a citizen $2,550 to see email exchanges between county employees and consultants, and the county estimated it would take 85 hours to process that request.

In another case, a physics instructor from Northeastern Junior College was told it would cost $30,000 to view emails from Attorney General Phil Weiser regarding a COVID database.

Roberts said that sometimes, the fees can cost more than a mortgage, forcing the public and the media to change requests, narrow topics — or give up altogether.

Critics: Bill allows universities to keep deals with athletes secret

Roberts and others are also worried about House Bill 1041, which exempts from the public right of inspection the personally identifiable information contained within an agreement or contract concerning a student athlete or a prospective student athlete’s name, image or likeness.

HB 1041 is moving quickly through the legislature and is likely headed to Polis’ desk.

Roberts said the problem with HB 1041 is that it helps public universities keep deals made with athletes a secret. That means a well-represented athlete will likely get a better deal than another athlete who doesn’t know the process as well.

“It just seems like it gives a public university a pass on how they are even going to be scrutinized if they are misusing the system. It really gives (public universities) a little bit of freedom,” he said.

Backers of HB 1041, including co-sponsor Sen. Judy Amabile, D-Boulder, said, “restricting public access to student-athlete compensation allows Colorado universities to be on a level playing field with other universities around the country.”

That, she said, is “essential for recruiting and competitive balance.”

As a data journalist, Fish said that she has done work for ESPN, noting that the salaries for every pro athlete in all four major sports categories are always readily available. A college athlete is essentially “semi-pro,” and wages and deals should be made public, she said.

Roberts said several other laws that didn’t get as much attention also affect the people’s right to know.

He noted a bill that sought to protect ranchers seeking money for livestock killed by wolves that were reintroduced in the state last year.

Senate Bill 38 would shield some personal and sensitive financial information in filing compensation claims. The governor signed the bill into law on Thursday.

While advocates said anonymity is needed because some ranchers have hesitated to submit claims due to fear of harassment, Roberts said it would “cut off scrutiny of government programs.”

Colorado Parks and Wildlife has approved over $340,000 in compensation to ranchers who lost animals in 2024.

Marianne Goodland and the Denver Gazette contributed to this story.