10th Circuit ponders immunity for Colorado Springs officer in hospital room tasing

Some members of the federal appeals court based in Denver appeared skeptical on Tuesday that a Colorado Springs police officer committed a constitutional violation when he tased a man for refusing to hand over a cell phone that contained suspected evidence of child abuse.

Last year, a trial judge allowed Carl Andersen Jr. to take his excessive force claim against Officer Vito DelCore to a jury trial, finding DelCore had instigated the physical confrontation in a Colorado Springs hospital room when no apparent threat existed.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit heard DelCore’s appeal this week, with at least one member seeming reluctant to deem DelCore’s force unreasonable in light of Andersen’s repeated resistance to handing over the cell phone.

“It’s where you’re entitled to something as an officer and the person won’t do that,” said Judge Harris L Hartz. “At some point, officers have the right to use force to make the person do that.”

But instead of tasing someone, countered Andersen’s attorney, Reid Allison, “the proper course of action is to say, ‘Put your hands behind your back. You’re under arrest.'”

“I totally agree that would be better police practice,” Hartz acknowledged. “That’s not what we’re to decide here. It’s what’s constitutionally permitted.”

The case of Andersen’s tasing revolved around qualified immunity, the judicial doctrine that shields government employees from civil liability unless they violate a person’s clearly-established legal rights. Typically, there needs to be a prior court decision putting officers on notice that their conduct is unreasonable. The trial judge acknowledged there was no case similar to Andersen’s, but denied qualified immunity to DelCore because he “created the need to use force.”

In April 2019, Andersen’s fiancée accidentally struck their 19-month-old daughter while backing out of the driveway. A helicopter transported the child to UCHealth Memorial Hospital Central in Colorado Springs, where the rest of her family joined them. However, the Andersen family would not cooperate with nurses seeking more information about the incident.

The nurses called the police, suspecting child abuse. The family similarly rebuffed responding officers, but they did learn from another family member about the possibility of a vehicle strike in Teller County, where the child lived. Sheriff’s Det. Anthony Matarazzo then traveled to the hospital from Teller County. He learned Andersen’s fiancée was reportedly texting others about the accident.

The fiancée denied sending the texts and Andersen took her phone for safekeeping. Matarazzo then asked DelCore, Officer Todd Eckert and Sgt. Carlos Sandoval, who were in the hallway, to assist with obtaining the cell phone to prevent the destruction of evidence.

Body-worn camera footage showed the men entering the hospital room of Andersen’s daughter, where DelCore immediately moved to grab the phone from Andersen’s pocket.

“Excuse me, you do not grab anything from my pockets,” Andersen snapped. DelCore responded that Andersen was “gonna hit the ground real hard.” He also brandished his taser.

After the officers attempted to persuade Andersen to relinquish the phone, DelCore moved behind Andersen because “I don’t want anybody behind you getting hurt.” He grabbed Andersen’s arm, warned he would tase Andersen and ordered Andersen out of the room. DelCore then tased Andersen twice. Andersen fell to the ground and a struggle ensued with the other officers.

DelCore also threatened to tase Andersen’s father, former Republican congressional candidate Carl Andersen Sr., who was in the room.

Prosecutors eventually dismissed charges of obstruction and resisting arrest that were filed against Andersen.

In March 2022, U.S. District Court Senior Judge R. Brooke Jackson sided with most of the officers on Andersen’s excessive force claim, concluding they acted reasonably in intervening to help DelCore subdue Andersen. But Jackson used a “broader lens” to look at DelCore’s actions, finding DelCore’s response to someone who was not physically resisting and was suspected of, at most, misdemeanor obstruction was unreasonable.

DelCore “created the need to use force by escalating the interaction at every turn,” Jackson wrote. “Officer DelCore encircled plaintiff, taser drawn, in order to initiate a physical altercation. Plaintiff barely had time to process, let alone respond.”

DelCore then appealed to the 10th Circuit. He claimed the “danger creation” rationale was “murky,” and faulted Andersen for not identifying a court decision putting DelCore on notice his actions were unconstitutional.

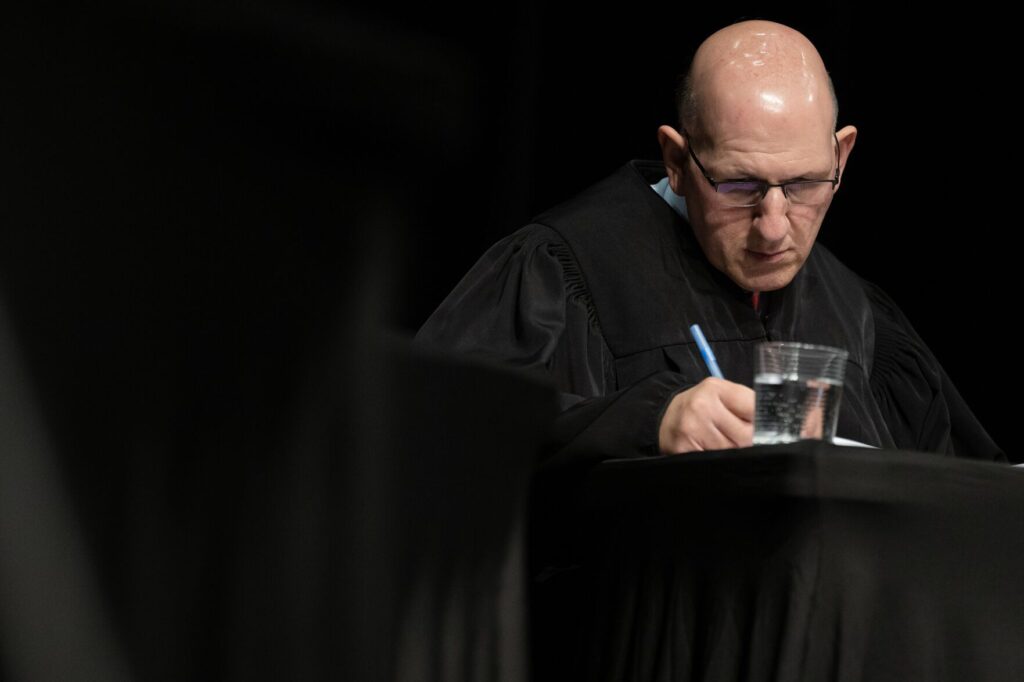

“Isn’t Fourth Amendment excessive force dependent upon the totality of the circumstances?” asked Judge Scott M. Matheson Jr.

Gordon L. Vaughan, DelCore’s attorney, responded that the officer’s actions before the use of force – a “seizure” under the Fourth Amendment – were irrelevant.

“I’m asking you to adopt a rule of several circuits that say you do not look to the pre-seizure conduct. That you look to what is occurring at the time of the incident,” Vaughan said.

Hartz observed that Andersen’s tasing fit a pattern with other recent appeals in the 10th Circuit.

“We’d had several cases in the last few months involving this other situation,” he said, “when an officer requests or demands a citizen to do something and the citizen refused to honor that lawful request. Officers don’t just have to say, ‘OK, too bad. You won’t do it so we can’t use force to make you do it.’ I think that’s not the law.”

Hartz asked whether the officers’ suspicion of child abuse could justify the use of force against Andersen.

“That is not what Judge Jackson found,” responded Allison.

The case is Andersen v. DelCore.