Appeals court tosses conviction, 32-year sentence after trial judge violated speedy trial right

Colorado’s second-highest court has overturned a man’s convictions for attempted murder and other offenses, and permanently barred prosecutors from retrying him because a Denver judge violated his right to a speedy trial.

The U.S. and Colorado constitutions guarantee criminal defendants the right to a speedy trial, which Colorado law mandates to occur within six months of a not guilty plea, with limited exceptions. If the government violates that directive, the legislature has established one consequence: dismissal of the criminal charges and a prohibition on prosecutors bringing the defendant to trial again.

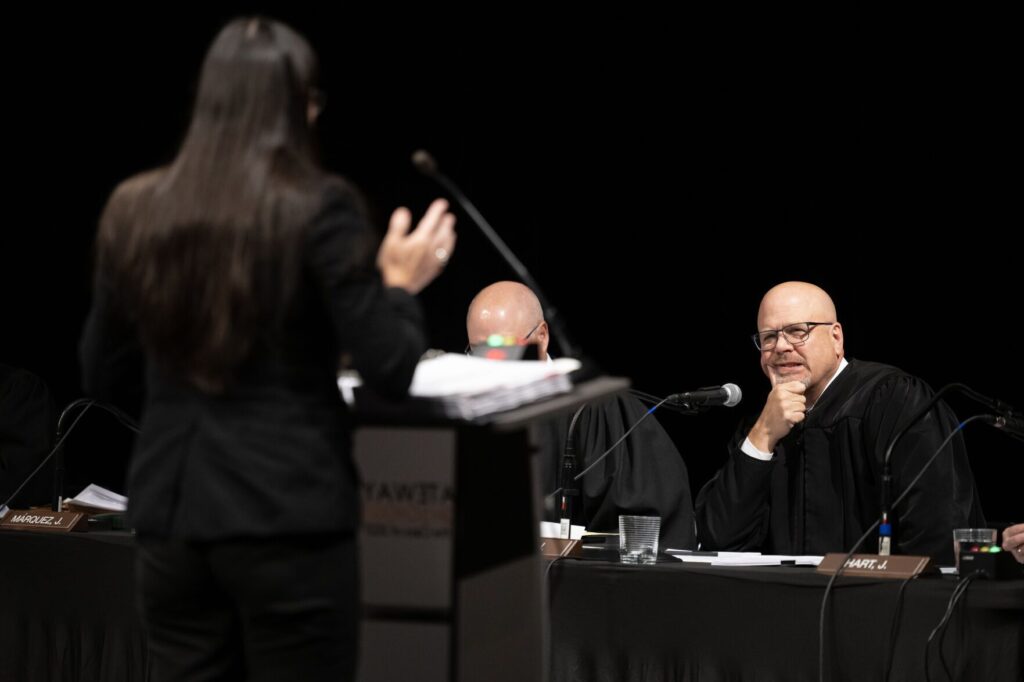

On Thursday, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals conceded Edward Martin Jones had gone to trial seven months after a judge entered a plea of not guilty on Jones’ behalf. Therefore, the panel reversed Jones’ conviction and accompanying 32-year prison sentence.

The circumstances surrounding Jones’ plea, however, were somewhat unusual.

Police arrested Jones in August 2018 after he shot an acquaintance near Colfax Ave. in Denver. Prosecutors charged him with attempted first-degree murder, assault and trespass.

Although Jones was found competent to stand trial, his behavior in the courtroom made it difficult for the parties to advance his case. He complained about his appointed lawyer, but then refused to say whether he wanted to instead represent himself. On multiple occasions, District Court Judge A. Bruce Jones had Edward Jones removed from the courtroom.

“You can take him and put him back where you found him,” Judge Jones said to security on one occasion.

In March 2019, Judge Jones attempted to take the defendant’s plea. He asked if Edward Jones was pleading not guilty.

“In the name of the law, what am I entering a plea for?” Edward Jones asked. “I don’t have to plead.”

Judge Jones then entered a not guilty plea on the defendant’s behalf, which state law requires in instances of no plea. Edward Jones continued to be disruptive and was removed. In his absence, Edward Jones’ “standby counsel,” who the judge appointed to represent the defendant only if it became necessary to end Edward Jones’ self-representation, asked for another arraignment. Judge Jones agreed and withdrew the not guilty plea.

In May, Judge Jones again entered a not guilty plea after Edward Jones refused to plead. He set the trial for October 2019, five months later. Edward Jones represented himself at trial and the jury found him guilty.

On appeal, Edward Jones argued Judge Jones violated his speedy trial right under Colorado law by setting a trial for seven months after the original entry of a not guilty plea in March 2019. But the prosecution maintained Judge Jones’ subsequent actions were appropriate because the standby counsel had requested more time before entering a plea, which finally occurred in May and gave the government plenty of time to try the defendant in October.

“Unfortunately, the not guilty plea had already been entered,” wrote Judge Ted C. Tow III in the appeals panel’s Dec. 8 opinion, disagreeing with the prosecution’s interpretation. Edward Jones’ standby counsel was not representing him, Tow explained, and could not withdraw the March guilty plea on Edward Jones’ behalf.

Judge Jones “had no authority to retract the not guilty plea during the March arraignment. Consequently, Jones’s speedy trial clock started when the court first entered the not guilty plea on March 8. When trial did not commence by September 8, Jones was denied his statutory right to speedy trial,” Tow concluded.

A spokesperson for Denver District Attorney Beth McCann said the office encourages the Colorado Attorney General’s Office to pursue an appeal to the Supreme Court.

The case is People v. Jones.