Appeals court orders new trial, further review after Adams County judge’s errors

An Adams County judge gave jurors an instruction that misrepresented Colorado’s drug possession law, prompting the state’s Court of Appeals last week to reverse the felony conviction of Ashley Morgan.

Moreover, a three-judge panel of the appellate court decided District Court Judge Priscilla J. Loew performed an incomplete analysis of whether an Adams County sheriff’s deputy interrogated Morgan in custody without first warning her of her Miranda rights. Although Loew determined a Miranda warning was unnecessary, the panel stopped short of endorsing Loew’s conclusion.

If it turns out after further review that Morgan was in custody and Deputy Isaiah Acosta neglected to inform Morgan about her constitutional rights to an attorney and against self-incrimination, it will result in the suppression of an incriminating statement she allegedly made during an unrecorded traffic stop – in which jurors could only evaluate Morgan’s word against Acosta’s.

It was just before 2 a.m. when Acosta pulled over a vehicle for running a stop sign and expired license plates. Morgan was the passenger. The male driver had recently purchased the car from another woman and it was reportedly still full of her personal items, including clothing, paperwork and “a lot of junk.”

Acosta allegedly saw Morgan make furtive movements in the passenger seat and she “kind of twisted” toward the back as he approached. Acosta spotted on the car’s center console a glass pipe with burn marks and white residue, along with a similar glass pipe inside of a black purse on the back seat.

The deputy had both occupants step out of the car and said he needed to pat them down for weapons. While frisking Morgan, Acosta asked whether Morgan had any belongings in the car.

There was no body-worn or dashboard camera footage of the stop, but according to Acosta, Morgan said the women’s clothing and “purses” were hers. Morgan later testified she did not say that, and her only purse was by her feet.

Acosta searched the car while another deputy watched over Morgan and the driver. The search uncovered methamphetamine in a container and also in the black purse. The driver pleaded guilty to drug possession, and claimed he had not told Morgan there were drugs in the car. Morgan went to trial on her own felony possession charge.

Morgan attempted to suppress her alleged statement to Acosta that the purses in the car were hers, arguing Acosta should have informed her of her Miranda rights because he interrogated her during the pat-down while she was effectively in custody. But Loew disagreed Morgan was in custody and declined to find Morgan’s Miranda rights were violated.

Morgan also took issue with an instruction Loew gave to her jury. Prosecutors only had to prove Morgan knowingly possessed a controlled substance to obtain a conviction. To that end, Loew instructed jurors that possession “may be established circumstantially; if the defendant has dominion and control of the premises in which drugs are found, the jury may infer knowledge.”

The instruction was a nearly-verbatim quote from a 2012 decision of the Court of Appeals in People v. Poe. There, probation officers searched a man’s apartment and found drugs. Although the defense asserted a houseguest actually brought the drugs into the home, the Court of Appeals noted the defendant was living alone and there was no evidence of a guest in the apartment.

Although Loew justified her decision to quote the Poe opinion by claiming the case was “solid law,” Morgan argued on appeal that neither Colorado law nor the model jury instructions supported the idea Morgan’s “dominion and control of the premises” could lead to a conviction.

The Court of Appeals agreed with Morgan that the instruction inaccurately stated Colorado law, based on the differences between the Poe case and hers. Poe involved a defendant whose premises – an apartment – were solely under his control. Morgan, as the passenger in a car allegedly littered with another woman’s possessions, was not in the same situation.

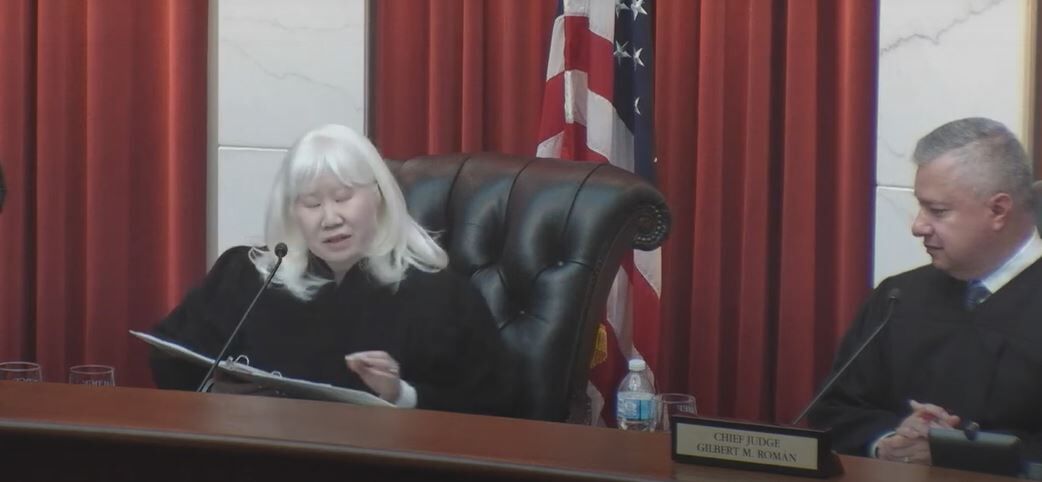

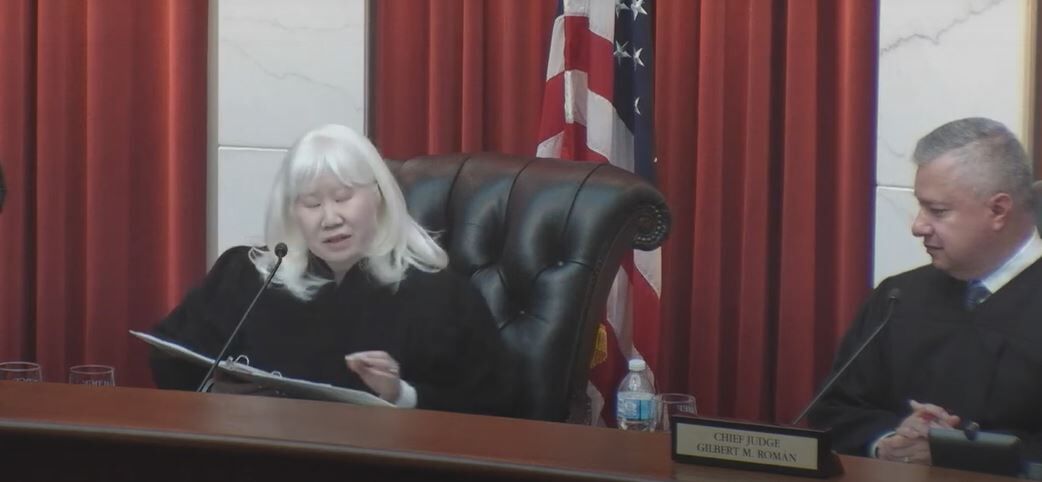

“Here, it was undisputed that Morgan was not the sole occupant of the car,” Judge Sueanna P. Johnson wrote in the panel’s Sept. 22 opinion. “Therefore, she did not have exclusive possession over the place where the drugs were found. As a result, although the jury could find that she possessed the drugs (because she had at least partial dominion or control over the black purse), it could not infer knowledge.”

Because there was evidence suggesting Morgan did not, in fact, know about the drugs in the purse, the appellate panel concluded the instructional misstep may have affected her conviction and it ordered a new trial.

The panel also addressed whether Acosta violated Morgan’s Miranda rights when he allegedly elicited an incriminating statement from her about the purses during her pat-down. The panel agreed Morgan’s alleged admission was made voluntarily and Acosta did not coerce her, but it could not say whether she was effectively in custody at the time of the questioning.

Loew had found Acosta’s tone was conversational and he “didn’t continue to push” in his interrogation.

“While she was being physically touched by an officer, the testimony was that she was free to go,” Loew said at the time. “That wasn’t verbally articulated to her, but he did not have a weapon drawn.”

Morgan argued Loew’s interpretation of the traffic stop defied common sense, explaining “no person would feel free to go while an officer frisks their body without consent.”

The Court of Appeals recognized that an officer’s questioning during a traffic stop does not always equate to placing a suspect in custody, but in Morgan’s case, it may have. Loew’s analysis did not mention there was a second officer present, that Morgan may have felt she would be arrested, or that Acosta solicited incriminating information after he had already spotted drug paraphernalia.

“Without findings on these additional factors, we cannot say that the totality of the circumstances supports that Morgan was not in custody at the time she allegedly told Deputy Acosta that the black purse behind the driver’s seat belonged to her,” Johnson wrote.

The panel ordered further analysis of the issue upon retrial. Because the Court of Appeals reversed Morgan’s conviction based on the instructional error, it did not address another claim Morgan had made on appeal: that Loew wrongly allowed multiple jurors to serve who indicated Morgan should have to prove she did not know drugs were in the purse. Morgan pointed out it was not her responsibility to prove innocence, but rather the government’s responsibility to prove guilt.

The case is People v. Morgan.