Judges, justices give candid look at judicial operations at educational conference

Six of Colorado’s seven Supreme Court justices and more than one-third of the state’s Court of Appeals on Friday provided a candid glimpse into judicial branch operations, with subjects ranging from pandemic recovery and recent precedent-setting decisions to the Supreme Court’s increased pattern of hearing appeals directly.

Among the key points raised at the 2022 Appellate Practice Update, the Supreme Court has decreased the amount of time taken to issue decisions in cases following oral arguments. Justice Monica M. Márquez acknowledged that the time to decide civil cases has decreased by 13% over the past year, while the time to decide criminal appeals has dropped by more than one-third. However, she offered explanations only for the general trend and avoided commenting on specific cases.

“You might be wondering, ‘How on Earth did it take that 7-0 opinion X number of days to get out the door?’ Those are the kinds of stories that will not be told, at least at this court,” Márquez said, in a veiled reference to the leaked draft opinion from the U.S. Supreme Court earlier last week.

The appellate practice event, sponsored by the Colorado Bar Association’s continuing legal education arm, brought dozens of judges and attorneys to the Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center to hear directly from high-ranking judicial officials about the latest developments in their courts.

The discussions also served to convey advice to lawyers practicing before appellate judges in the state, and to alert them to major shifts within the branch.

Judge Craig R. Welling of the Court of Appeals noted that during the pandemic, oral arguments were conducted online, and they still are occasionally. But the current choices are binary: to have arguments exclusively in-person or solely by Internet. That may soon change to allow for a hybrid format.

“We’ve bid it out to get the technology so that in a year or so, we’ll be able to have some people in the courtroom and some people are remote,” Welling announced.

Statistics

In the fiscal year spanning 2020-2021, 1,500 cases were filed with the state Supreme Court, a slight increase over the prior year. In the Court of Appeals, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a drop-off in filings in mid-2020, and total criminal and civil case filings are still at depressed levels.

Those were among the statistics Geoffrey Klingsporn, a lawyer with the Denver City Attorney’s Office, highlighted in an analysis of appellate caseloads. Klingsporn, who has presented a version of his findings for nearly the past decade, also looked closely at the approximately 100 opinions the Supreme Court issues annually.

Notably, Klingsporn found that both the time the Supreme Court takes to hear cases and the time the justices take to decide cases following oral arguments have decreased since 2013. The decrease was particularly pronounced for criminal appeals.

That trend “means fewer days of anxiety for lawyers and their clients,” Klingsporn noted. On average, parties to a case can expect to wait approximately six months after oral argument to receive a decision. In a handful of circumstances – all involving the new commissions that redrew legislative boundaries following the 2020 Census – decisions came down in under one month.

Klingsporn also explained that decisions of the court were largely unanimous, with Justices Carlos A. Samour Jr. and Richard L. Gabriel authoring the most majority opinions.

Márquez, reacting to the findings, said the general trends were not illustrative of the “wild twists and turns” that sometimes happen behind closed doors, but that the Supreme Court has indeed made an effort to speed the process. Currently the longest-serving justice, Márquez said it is no longer the case that the court hears large batches of appeals at once, which used to crowd out other key tasks.

“We’ve smoothed that out by holding fewer arguments more frequently,” she explained. “That small tweak has made a tremendous difference in allowing each of the justices to keep up with the cases in their bucket throughout the year.”

Márquez added that the Supreme Court is hearing appeals as soon as they are ready for oral argument, having caught up with all of its pending cases.

Update from the chiefs

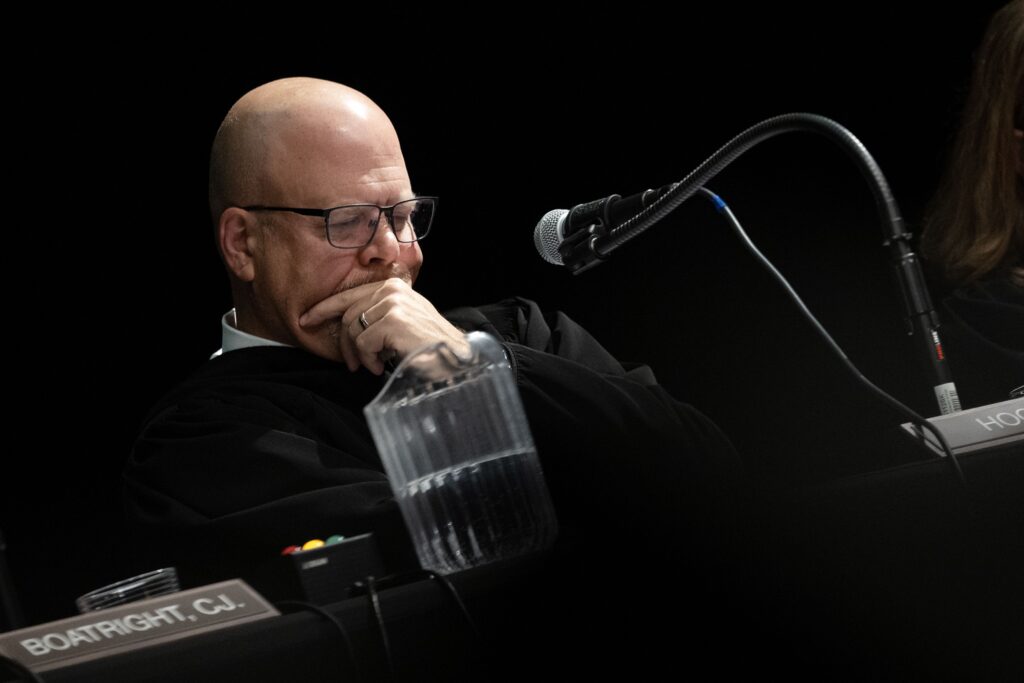

The chief judges of Colorado’s three appellate courts briefly addressed attendees about the recent updates in their respective institutions. Márquez delivered the Supreme Court’s message on behalf of Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright, who was recovering from COVID-19.

“We have just been so impressed by the creativity, the grace, the grit and the determination our trial judges and staff have shown across Colorado as they have navigated all sorts of unprecedented challenges in the past couple of years,” she said.

Court of Appeals Chief Judge Gilbert M. Román, who is in his first year in the top job, identified several upcoming vacancies among senior court staff, and also pointed to significant turnover within the 22-member appellate court. Beyond the nine judges appointed since January 2019, there are three more planned retirements in the next two years.

Román explained that during the pandemic, his court decided there would be one fewer case than usual assigned to each panel of three judges, known as a division, that hears appeals.

“That was the right thing to do. Work-life balance is important. Mental health is important,” he said. “But we also knew it would create a pandemic backlog.”

Judges are currently working on extra cases to help reduce the backlog, Román added.

Also present was Chief Judge Timothy M. Tymkovich of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit. Based in Denver, the 10th Circuit hears appeals of federal cases from Colorado and five neighboring states. Tymkovich said his court has experienced a long-term decline in caseloads, notwithstanding the population growth in Colorado.

The first in-person oral arguments since the pandemic began took place in March, and the 10th Circuit’s courthouse now allows for hybrid proceedings as well as live audio streaming during oral argument weeks.

“In the future, I suspect that instead of having every panel in Denver for all five days, we can have one Zoom panel on a day where we don’t think the cases are complex enough to warrant in-person oral argument,” Tymkovich speculated.

Supreme Court’s acceptance of cases

Justices William W. Hood III and Melissa Hart discussed two categories of appeals that the Supreme Court may hear directly, without a prior decision from the Court of Appeals. Last year, the Supreme Court granted 13.5% of petitions in so-called Rule 21 cases, which challenge decisions of the trial courts. That is a significant increase from recent years.

“I’m willing in many instances to assume the trial court made a mistake. But this is an extraordinary remedy,” said Hood. “What I pay most attention to is why we should exercise our original jurisdiction. Why should we pluck this from the usual scheme of things and focus on it now?”

Each Rule 21 petition goes to an individual member of the Supreme Court. That justice will review the case and author a memo with a recommendation. Hood and Hart suggested that such requests be brief and avoid a “tone of aggrievement” about a trial judge’s handling of the case.

Many recent Rule 21 cases pertained to pandemic-related issues, like masking in courtrooms or the speedy trial deadline in state law. Unlike standard requests for appellate review, which require the agreement of three justices to hear the case, Rule 21 petitions require four votes. The most important factor, said Hood, is the “now-or-never” rationale for requesting Supreme Court intervention.

“There are instances where it’s just something of public importance and we don’t want to wait a couple years for this issue to find its way back to us,” he said. “Maybe it’s something that’s happening with sufficient frequency that we decide we should just jump in now.”

Related to Rule 21 cases are petitions under Rule 50, which takes cases out of the Court of Appeals and transfers them to the Supreme Court, either at the request of the parties or from the appellate court itself.

“I think 99% of the time it’s because of a timeliness question,” said Hart. The Supreme Court heard a Rule 50 case as recently as last week, considering the constitutionality of the state’s paid leave program before premiums on employer payrolls take effect in 2023.

“There’s no time for the appellate process. That was a no-brainer,” she said.

Criminal law updates

Justice Richard L. Gabriel, along with Court of Appeals Judges Terry Fox and Neeti Vasant Pawar, reviewed key recent decisions from their respective courts that laid down new precedent in criminal law.

For example, the Supreme Court in January provided new direction to trial court judges who attempt to explain the concept of reasonable doubt to jurors, after a long string of Court of Appeals decisions warned against such illustrations.

“To trial courts, with great respect, don’t do this anymore. Just don’t,” said Gabriel. “Don’t try to give your own examples. You’re not gonna get in trouble that way.”

The panel also raised the topics of racial discrimination in jury selection, the timeliness of judges ordering restitution payments, and expert witness testimony, all of which have surfaced as major issues on appeal.

Oral argument

Attendees heard from judges about their views on oral arguments, which take place in most Supreme Court cases but only a minority of Court of Appeals cases.

“In almost every case, our opinions in the Court of Appeals become better with the result of argument,” said Welling. “Less commonly, outcomes change.”

What hurts attorneys during oral argument, the panel said, is when they cannot gracefully concede that a particular point is not in their favor. There is lost credibility when lawyers refuse to concede clear facts.

“I think you’re prepared for it and say, ‘Here’s why it doesn’t matter’ or ‘Here’s why I can’t fully make that concession’,” said Judge Stephanie E. Dunn of the Court of Appeals.

Finally, Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. advised lawyers to think through how a court’s decision in their favor would affect other hypothetical situations. At the same time, imagining every possible scenario is not possible, and attorneys should think quickly on their feet.

“Welcome softball questions,” Samour said. “I’m throwing you a softball question because I’m trying to convince one of my colleagues, but you’re fighting me!”

Diversity

Last year, the Colorado Supreme Court mandated that lawyers undertake equity, diversity and inclusivity training as part of their continuing legal education. The content of the trainings must cover equal access to the legal system, representation of diverse populations, and the recognition or elimination of bias in the legal profession.

Márquez traced the history of the idea to 2014, but said it was ultimately the racial justice protests that ensued after Minneapolis police murdered George Floyd in 2020 that reinvigorated the desire for training.

“We felt the very visceral impact of that and the impact it placed on the court. Going through that as a group of seven, I believe, shifted some perspectives on the need for this type of requirement,” she said. Márquez added that the rule change was aimed at instilling “culturally-competent representation” into lawyers’ work and ensuring that judges avoid making erroneous assumptions about the people who appear before them.

Framing the appeals

Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter and Court of Appeals Judge Rebecca R. Freyre emphasized to attorneys to be mindful of the different standards for reviewing a trial court judge’s alleged error, and also the standard for reversing a decision if, in fact, there was an error.

“There is no such thing as an error-free trial. We’re human beings. It’s going to happen,” said Freyre.

Joining the two appellate judges was U.S. District Court Judge Christine M. Arguello, who, in her position as a federal trial judge, sometimes reviews the work of magistrate judges or government agencies before rendering a decision. She recalled disagreeing, in one instance, with how the appellate courts applied a legal standard. She said she wrote an opinion that followed the rules, but gave the 10th Circuit an inroad to change them.

“When I got the reversal, I was like, ‘Yes, I changed the law!'” Arguello said. “Making those arguments at my level, the district court, is important because even if I rule against you, I have given enough to the 10th Circuit to reverse it.”