State Supreme Court adopts new accountability standard for prosecutors

The Colorado Supreme Court has clarified the circumstances under which prosecutors may face professional sanctions for failing to disclose information that they know, or should know, would cast doubt on the guilt of the criminally accused.

The rule change also quietly reversed the high court’s two-decade-old precedent requiring disclosure to defendants only when evidence is “material to the outcome of the trial.”

Representatives of prosecutors and defense attorneys had presented the Supreme Court with a proposal to revise Rule 3.8(d) in the state’s Rules of Professional Conduct, making it easier for prosecutors who withhold relevant information to be held accountable for acting in bad faith. Longstanding court precedent has held that depriving the defense of favorable information affects the constitutional right to a fair trial.

“The world has very much changed. We are under more intense scrutiny … and we accept the responsibility of making sure people are not wrongfully convicted or make poor decisions in a criminal case because they did not have the information they should have,” Daniel P. Rubinstein, district attorney of Mesa County and a member of the working group, told the justices at a hearing last month.

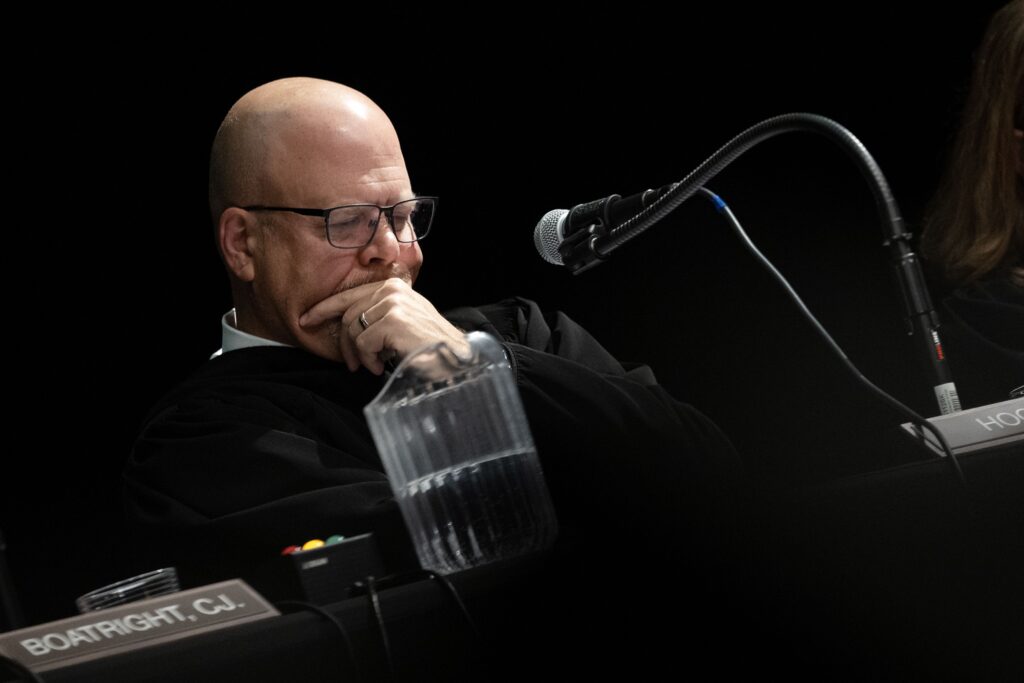

Some members of the court balked at the original proposal, believing it went too far beyond what other states required of their prosecutors. The draft required prosecutors to turn over information that affects “a defendant’s critical decisions” in their case.

As adopted, Rule 3.8(d) now focuses on information that affects a person’s decision on whether to accept a plea deal. At the same time, the revised rule mandates that prosecutors consider the key stages of a criminal case in their timing of disclosures to the defense.

Rubinstein told Colorado Politics that some of the changes the justices made are more protective of prosecutors compared to the original proposal, but “most of the modifications made by the Supreme Court are varied language of the same goal our group was trying to accomplish.”

Among the other adjustments, Rule 3.8(d) would require prosecutors to alert the defense if they are unable to obtain relevant information from other agencies, such as police departments.

The Supreme Court also chose to impose the professional obligation on prosecutors to share information with the defense regardless of the information’s effect on the outcome of the trial. That is a departure from a 2002 decision from the court that interpreted the disclosure requirement.

In that ruling, Colorado’s justices referenced the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brady v. Maryland, in which a prosecutor withheld the murder confession from another man in the defendant’s case. The court in its 1963 decision labeled the suppression of evidence favorable to the accused as unconstitutional if the information is “material either to guilt or to punishment.”

Critics have pointed out that because Brady pertains to information that prosecutors know and the defense does not know about, compliance depends upon the good faith of individual prosecutors.

Nevertheless, Colorado Supreme Court previously elected to incorporate the Brady standard into Rule 3.8(d), deciding that only if evidence would materially affect the outcome of the trial do prosecutors have to disclose it.

In its final form, the rule now applies to information regardless of how it might affect the outcome.

The Supreme Court received comments from defense attorneys supportive of the rule in principle. The U.S. Attorney’s Office sent a 10-page letter to the court in opposition.

“I don’t believe that the average prosecutor is unethical or meaning to be unethical,” testified public defender Ben Longnecker to the court, but “they shouldn’t be able to just simply dismiss cases when they mess up.”

The Supreme Court adopted the rule change on Feb. 24, but it does not take effect until July 1.