Political protests seem at all time high, but do they work?

Protests, email and letter writing campaigns targeted at members of Congress and packed town hall meetings have seemingly become the norm since Donald Trump assumed the presidency. Opposition is nothing new to anyone who’s sat in the Oval Office – or in any elected office for that matter – and tried to carry out new policies and change what seems to be an unchangeable bureaucracy.

Still, the level of that opposition seems more vocal, more amped up than at any time in perhaps decades. Millions marched on Washington, D.C, the day after Trump took the oath of office as the 45th president. Thousands marched in opposition to abortion and hundreds of people have attended town hall meetings in Colorado and other states, voicing opposition to issues such as changing or repealing the Affordable Care Act, Trump’s executive orders related to immigration from certain Muslim-dominated countries and building a wall between the U.S. and Mexico.

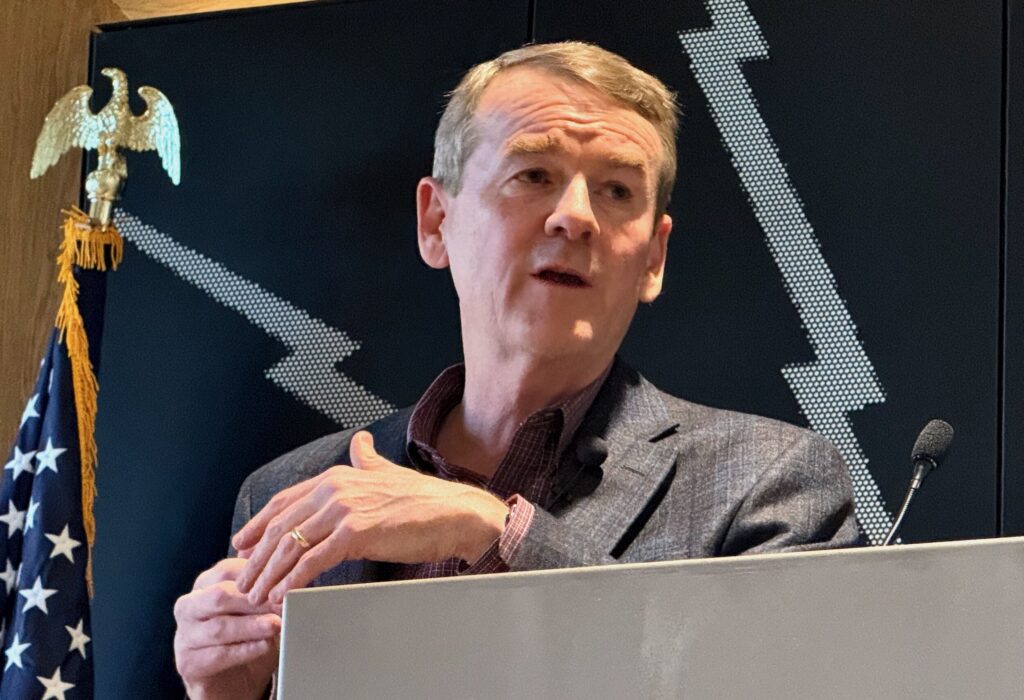

There doesn’t seem to be a shortage of issues for Democrats and their supporters to rally against, but a Metropolitan State University associate professor of political science, Robert Preuhs, said a sustained effort is a key to the success of any protest movement.

“It’s a useful method when it lasts, like the Civil Rights and (anti-) Vietnam War movements in the 1960s,” he told The Colorado Statesman in an interview. “But historically, these types of protests turn out to be relatively short because they don’t have the numbers and support to sustain any momentum they might have at the start.”

A cohesive organization is a key to maintaining momentum, especially when there are several different groups involved, Preuhs added.

“Right now what we see is the usual antipathy toward whoever is president was shocked when Trump won the election. The protesting groups feel they can influence the decisions before Congress through an outsider strategy.”

Still, there hasn’t been much evidence of that strategy working. For example, despite a strong campaign against Beverly DeVos as secretary of education, opponents were unable to convince a third Republican to vote against her nomination. Vice-president Mike Pence cast a historic tie-breaking vote in her favor, the first time a presidential nomination was decided that way.

“That highlights the level of partisanship that dominates in the (U.S.) Senate,” Preuhs said. “Protests can usually affect folks who are at the margin of some issue, but they haven’t been a realistic way to change these strong levels of partisanship.”

In Colorado, U.S. Sen. Cory Gardner, R-Yuma, was strongly lobbied to vote against DeVos, but never wavered in his support. Shortly after Trump nominated DeVos, Gardner issued a statement of support. However, Preuhs noted Gardner was critical of Trump’s immigration moves and words of support and admiration for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The demographics of a Congressional district and state also play a role in how an official responds to protests and lobbying by activist groups, he said.

“People like (U.S. Rep. Doug) Lamborn and (U.S. Rep. Diana) DeGette don’t have as much to worry about,” Preuhs said of Lamborn’s strongly Republican district and DeGette’s Democratic-dominated district. In contrast, Gardner and U.S. Rep. Mike Coffman, R-Aurora, are two Washington officials who might be more likely to listen to opponents, he noted.

Numbers show strong interest

While street protests are the more visible form of opposition, email and letter writing campaigns targeted at members of Congress serve other purposes.

“You can get a sense of intensity when thousands of emails are sent, but that can be discounted by the ease with which those comments can be deferred,” Preuhs said, especially if an opposing group provides email templates to its supporters. Such similarly worded messages are usually tallied up but can be more easily ignored, he said, especially if a Congressional office staffer finds most authors are from outside that Congressional district or state.

“Most elected officials are concerned about how they appear to party leaders and their reelection chances. But if there’s a great number of letters, emails and calls, it at least lets that official know there is a great amount of opposition to an issue.”

Packing town hall meetings is another Tea Party-related tactic, Preuhs said, that can be more effective because it’s face-to-face.

“Nowadays, they’re often videotaped and the risk for protesters is they look more radical or portray themselves as negative. For an official, they can come off as not caring or even kind of running away.”

If such actions become commonplace at several town hall meetings, Preuhs said an official might cancel them out of security concerns as well as not wanting to face repeated criticism.

Even with social media able to whip people into a frenzy over any issue these days, Preuhs added that there still needs to be “mass concern” by citizens.

“If not, then the calls for action on Facebook or whatever just become a ‘protest-of-the-day’ type of thing and they lose their effectiveness. Right now, we’re more polarized as a country than we’ve been for a long time. There’s a lot of hostility out there. So we’ll see.”