The future of Colorado water: How the fight over Shoshone water rights affects the Front Range

A million acre-feet of water in the Colorado River — and the efforts by Western Slope water partners to keep it there — became the subject of a recent two-day hearing that could decide just who gets water and how much.

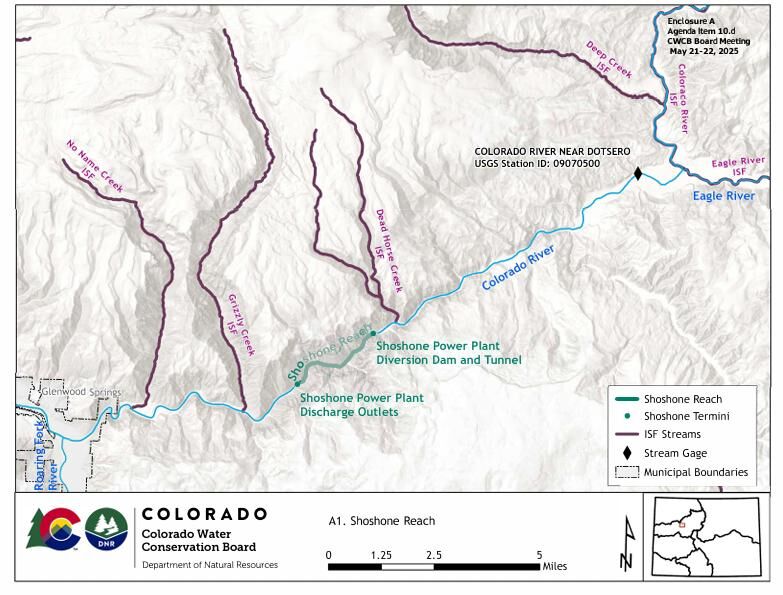

One of the major points of tension is the objection by several water providers — not to the deal, per se, between a subsidiary of Xcel Energy and the Colorado River Water Conservation District and its 32 partners — to keep the water in the river that flows through the Public Service Company of Colorado’s Shoshone hydropower plant six miles east of Glenwood Springs in the Colorado River.

Public Service Company of Colorado (PSCo), the Xcel subsidiary, would still retain lease rights for that water, according to the deal.

Rather, the conflict revolves around the details of the legal agreements regarding junior water rights.

Indeed, the challenge is complex, tied to an interconnected set of issues that includes water rights, drought management and who gets to decide whether to withhold water from going downstream, if the situation warrants it.

The river district has raised almost all of the $99 million needed, although about $40 million is on hold under a decision by the Trump administration to suspend last-minute funding awarded by the Biden administration out of the Inflation Reduction Act.

Funding, however, is now just a small part of the efforts.

The water flowing through the Shoshone plant is “non-consumptive,” meaning what goes into the plant to generate hydropower flows right back out into the river with no negligible loss.

The water then supports recreational and environmental needs, as the river heads west. The water rights date back to 1902 and are the most senior on the river.

That makes them valuable and desirable.

And that’s what’s at stake.

With the funding issue nearing completion, the next step is to make legal changes in how the water rights are defined, which brought in the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB).

Under legislation passed in 1973, the water conservation board is the only entity that can legally appropriate water rights to preserve instream flows, defined as a “beneficial use” of that water.

Under the board’s instream flow program, the agency has appropriated instream flow water rights on nearly 1,700 stream segments covering more than 9,700 miles of stream, including rivers.

These rights, according to the board, preserve and even improve the natural flows of those streams and rivers.

The Colorado Water Conservation Board and the River District want to see the Shoshone water rights designated as instream flow, since legally, that water can only be used presently for hydropower.

And despite the controversy that has been brewing for more than a year, nobody actually disagrees with doing that.

What’s now at issue is just how that’s going to be defined, including how much water would be dedicated to the instream flow.

In order for the water conservation board and the district to add instream flow as a beneficial use in water court, the CWCB first has to approve it.

Under the designation as an instream flow, the CWCB would not own the water right. That would stay in the hands of the river district and its partners.

But the CWCB would have a legal interest in the water right and it would be contractually obligated to manage it, along with the river district, for instream flow purposes.

It’s the first time the CWCB has entered into an agreement to share management of a major instream flow with an outside entity.

It’s a two-step process, according to CWCB Director Lauren Ris.

The river district first had to make an offer to the CWCB, which happened in May. Then, CWCB would decide whether to accept, based on a biological assessment conducted by Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

That assessment would decide whether the water right would preserve and improve the natural environment. Staff agreed that it would.

The analysis said the proposal “is a valuable additional beneficial use of the historical Shoshone Power Plant water rights to preserve and improve the natural environment by restoring flows in the depleted reach of stream and improving river connectivity and habitat.”

The water right is a relatively short section of the river, just under 2.5 miles, the analysis pointed out.

But its importance cannot be understated, and the state has had its eye on preserving those water rights for decades.

“The proposed acquisition represents a rare opportunity for an important public-private partnership regarding operation of a large water right that has been, and will continue to be, important to most of the major water providers and water users in both the west slope and east slope of Colorado,” the analysis said. “The Shoshone Water Rights, although physically impacting a relatively short reach of stream, because of its magnitude and location of operation can have an effect on a large part of the entire state of Colorado.”

The board would vote on approving the use of that water right as an instream flow, and then with the river district and the Public Service Company of Colorado, apply to the state’s water court for approval.

In between the vote and the application to water court, however, is an appeal process.

That’s where things stand now and that’s what the two-day hearing on Sept. 17-18 was for.

Water providers object

Four Front Range water providers — Aurora, Colorado Springs, Denver and Northern Water, which provides water for northern Front Range cities and towns and agriculture — objected.

Collectively, about 500,000 acre-feet of water annually flows to those providers through four transmountain diversion tunnels. That water also feeds 10 Front Range reservoirs.

The CWCB in July approved the hearing.

In a June 9 letter, Denver Water said, “The proposal will change, rather than maintain, the status quo in ways that would hurt Denver Water’s ability to provide water to the 1.5 million people we serve during severe or prolonged drought.’’

The Colorado Springs Water District echoed those worries in a June 9 letter requesting an official hearing.

The water agency said it is “concerned that the River District’s proposed methodology for determining the historic use of the senior and junior Shoshone water rights will result in the expansion of Shoshone water rights, especially the junior right, that could materially injure (Colorado Springs Utilities) decreed water rights, including its water rights on the Blue River and its interest in the water rights for the Homestake Project by reducing the volume of water available for diversion under those rights.”

Once that first hearing took place in May, the board had 120 days to conduct a fuller hearing process and make a decision, unless the proponent agrees to an extension. The river district agreed to do so, in hopes — Ris said — that a negotiated solution that could be worked out.

But that extension only goes to the CWCB’s November board meeting.

Ris said that when someone goes to water court to add another beneficial use, the water has to quantified, under something known as historic consumptive use. That’s the amount of water actually being put to beneficial use.

That’s a little confusing because there is no consumptive use of the water presently, and the staff analysis said state law on historic consumptive use would not apply. In this case, the intention is to use an historic use, rather than a consumptive use.

How that is determined is by how that use is measured and in what time period, known as a study period.

That’s where the fight is now.

Ris explained that the fight is over the methodology on determining the water quantity.

Front Range water providers are concerned that the preliminary analysis that came from the River district would be an expansion of the status quo.

Who makes the ‘call’?

Why that matters is more than worries about the methodology — it is a concern about who gets to make a “call” on the river.

A “call” is when a senior water rights holder can demand restrictions on the water for a junior water rights holder. In this case, everyone except the river district hold junior water rights, including the Front Range water providers, who tap the Colorado River through transmountain diversions to supply water all along the Front Range and to millions of Coloradans — that’s about 85% of the state’s population — not to mention other uses, including industrial and agriculture.

A call would keep the water in the stream and not send it downstream to the Front Range, Ris said.

According to Ris, the water providers would prefer that decision be made by the CWCB, not the river district. It’s a matter of trust, or the lack thereof, for both sides, she said.

Over the years, a number of agreements have been made that govern a call. And, during times of drought, calls on the Shoshone water can be limited.

The water providers want those side agreements to remain in place going forward. As noted in a prehearing statement by Aurora Water, the agreement would affect both the senior water rights, as well as the junior water rights, held by Front Range water providers.

There’s also an issue with how those agreements are interpreted and when they apply, Ris said. That would likely have to be sorted out in the water court process.

Once the application goes to water court, however, there’s still opportunities for mediation and a settlement.

Water court applications are usually a lengthy process, unless all parties reach a settlement.

It would also allow all affected parties to present their own analyses. The staff analysis said the parties could use “various types of measures, models, and operations regarding historical stream flow, diversions, administration, reservoir releases, water rights analysis, and power generation,” as well as modeling and bringing in their own water experts.

Once that process is over, two more steps needs to be accomplished. The first is to go to the Public Utilities Commission (PUC), which has statutory oversight over Xcel Energy.

If the PUC signs off, then the application returns to the CWCB for a final check-off. If everything is up to snuff, the CWCB then writes the $20 million check that reflects the state’s contribution to the deal.

At the hearing’s onset, Ris acknowledged that emotions may run high on the issue.

In the two months between the CWCB’s decision to hold the hearing and Sept. 17, the agency received hundreds of public comments, almost all in support of granting the instream flow rights.

She told Colorado Politics that everyone feels strongly about this because “virtually everyone in Colorado is somehow impacted by the Colorado River.”

In a prehearing statement, Colorado Springs Utilities said it supports the instream flow rights but only for senior rights, and not for changing the junior water rights tied to Shoshone. The utility said it believes the river district’s analysis overstated the historical diversions of water and that its modeling underestimated the impact to upstream water users — aka the Front Range water providers.

In its statement, Denver Water said CWCB’s acquisition “would be a win for the State of Colorado if done in a thoughtful manner that protects existing water rights from material injury.” Its concern is over the call, tied to when the hydropower plant goes down for repair or maintenance.

It’s not merely a hypothetical concern: The plant was shut down for six months last year.

When that happens, according to a 2016 agreement known as the Shoshone outage protocol, “junior water rights cannot store or divert water without providing replacement water to offset their depletions to the river system as necessary to prevent injury.”

When the plant is shut down, the call cannot be exercised, and river flows may drop.

It’s also a concern during times of drought. When that happens, the call can be “relaxed” to allow for water to continue to flow to the Front Range.

The instream flow agreement would require the CWCB and the river district to both agree to reduce the call in times of drought.

The outage protocol, according to Denver Water, protects its share of the water when the plant shuts down.

If the CWCB disregards the outage protocol, it will impact the water supply Denver Water distributes to 1.5 million customers. The water provider asked for the protocol to be incorporated into the agreement.

That’s also similar to the position of Northern Water.

Aurora Water stated the instream flow agreement violates existing contractual arrangements, and asked that the whole process be delayed until the river district comes up with an agreement that would comply with those arrangements.

Andy Mueller, general manager of the River district, told the CWCB board during the hearing that the choice is whether to side with the river district or the Front Range.

As to the call, at the heart of the issue dividing the two sides, Mueller said the the river district is “willing to fall on our sword” to ensure management of a call remains jointly with the CWCB and the river district.

Will the two sides come up with a settlement before the CWCB’s Nov. 19-20 meetings?

The river district’s decision to agree to an extension signals a willingness to continue working. But in the end, Mueller indicated it’s up to the Front Range water providers, too.

CWCB Chair Lorelei Cloud told Mueller that if the agreement is to happen, the two parties — meaning CWCB and the river district — have to work together, regardless of who sits on the CWCB in the future. But the CWCB, for now, is not being asked to support the river district’s analysis as it pertains to historical use, Mueller said.

The river district has agreed to come up with language changes.

At the end of the two-day hearing, the board deliberated for about two hours.

“We have participated in good faith” for a number of years on this issue, Ris told the board. With the help of the attorney general’s office and the instream flow staff, she is committed, she said, to working toward “a collaborative solution and a path forward” for the board when it comes back in November.