Colorado’s new ‘reasonable doubt’ instruction upheld, despite cautions from some appeals judges

Colorado’s second-highest court has upheld the recently reworded definition of “reasonable doubt” that appears in the template jury instructions for criminal trials, which generated controversy at the time of its debut.

In a pair of precedent-setting opinions issued the same day last week, two separate panels for the Court of Appeals found no legal deficiency with the instruction as currently worded.

However, in an unusual move, the six judges across both opinions harbored three different views about a key portion of the reasonable doubt definition.

The longstanding reasonable doubt instruction directed jurors to consider the evidence or “lack of evidence” in a case. When the judicial branch released the overhauled jury instruction in 2023, the text omitted “lack of evidence.” One year later, the committee tasked with revising the template instructions restored the phrase without explanation.

While it may be better to remind jurors they can consider what evidence did not get presented, “we hold expressly that a court does not err by omitting that language,” wrote Judge Karl L. Schock in one of the May 15 opinions.

“Notwithstanding the noted authorities from other jurisdictions,” countered Judge Timothy J. Schutz in the other opinion, “we conclude that a trial court should inform the jury, as part of the reasonable doubt instruction, that it may consider the lack of evidence in the case.”

Judge Craig R. Welling, who sat on the same panel as Schutz, went further. He wrote separately to argue it was an error for judges to omit the “lack of evidence” line over a defendant’s objection, notwithstanding what the template jury instruction briefly said.

“This, in my view, is one of those exceptionally rare circumstances where tracking the model instruction alone isn’t enough to save the court’s decision,” Welling wrote.

Two defendants who were convicted at trial challenged the use of the 2023 language, arguing it lowered the prosecution’s burden to prove them guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Previously, the model instructions for Colorado explained reasonable doubt in a more complex fashion. Reasonable doubt was a doubt, based upon reason and common sense, and which was not vague or speculative, that would “cause reasonable people to hesitate to act in matters of importance to themselves.”

The Model Criminal Jury Instructions Committee, composed entirely of judges, released new language in January 2023, directing jurors that if they are “firmly convinced of the defendant’s guilt, then the prosecution has proven the crime charged beyond a reasonable doubt.” Then-U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg endorsed the wording in 1994 as a “clear, straightforward, and accurate” definition of reasonable doubt for jurors.

While both prosecutors and defense attorneys were surprised by the abrupt revision, the defense community was alarmed about how the new wording would affect their clients.

“This occurred without any opportunity for input from any other criminal legal system stakeholders,” said James Karbach of the state public defender’s office. “As defenders of the poor and marginalized, our initial reading is that this change unfairly favors the government and will lessen the burden of proof in everyday jurors’ minds and make it easier to overcome the very important presumption of innocence.”

In the 2024 version of the template instructions, the committee added one sentence instructing jurors once again that they could consider “the evidence presented or the lack of evidence presented” when evaluating reasonable doubt. The committee gave no reason for the addition.

In 2023, Mesa County jurors convicted Kyle R. Schlehuber of a felony impaired driving offense. The same year, Boulder County jurors convicted Nelson Melara of two child sex offenses. Both sets of defense counsel objected to the revised reasonable doubt instruction. Melara’s attorney argued against using the trial as a “test case” for the new language.

On appeal, the defendants challenged multiple aspects of the revised instruction. Melara’s attorney pointed out his first trial — using the old reasonable doubt instruction — resulted in a hung jury, whereas the 2023 trial with the new language resulted in a conviction. Schlehuber’s attorney added that the subsequent re-insertion of the “lack of evidence” was a “clear indicator” the 2023 instruction was flawed.

Schock, writing the opinion for Schlehuber’s case, acknowledged the template jury instructions are not immune from legal challenge simply because the revision committee approves of them. However, he concluded the challenged phrases “work together to give the jury a complete picture of the reasonable doubt standard.”

Although courts have upheld the validity of the pre-2023 language, “just because a proposed instruction is a correct statement of the law does not mean the instruction must be given or that it is the only correct way to articulate the applicable law,” Schock wrote.

The panel for Melara’s appeal reached the same conclusion, but spent significant time discussing whether it was problematic that the 2023 revision failed to instruct jurors they could consider the lack of evidence when determining guilt. Melara’s judges were more critical of the omission than was Schlehuber’s panel.

The committee’s initial choice to exclude that line “seems to have been a solution in search of a problem (or an oversight), and it runs contrary to the supreme court’s repeated cautions against unnecessary modification of the reasonable doubt instruction,” wrote Schutz for himself and Judge W. Eric Kuhn.

Moreover, continued Schutz, the lack of explanation for the phrase’s sudden reappearance a year later “is at least an implicit acknowledgment that there was no need to remove the phrase.”

Although the majority agreed Melara’s trial judge should have informed jurors they could consider a lack of evidence — despite the template language — Schutz noted the instruction did not forbid jurors from doing so. Therefore, the panel upheld Malara’s convictions.

Welling, in his concurrence, likewise believed the jury instruction as a whole suggested that jurors could consider a lack of evidence, but he also felt there was “no rational basis” for the trial judge to omit the language after the defense objected.

“As I read the opinions, all five of the judges who have signed on to those opinions are sending the same, strong message: It’s better practice for trial courts to include the ‘or lack of evidence’ language in the reasonable doubt instruction,” he wrote. “I would send the same message, just on the added basis that failure to include this language upon a party’s request is error.”

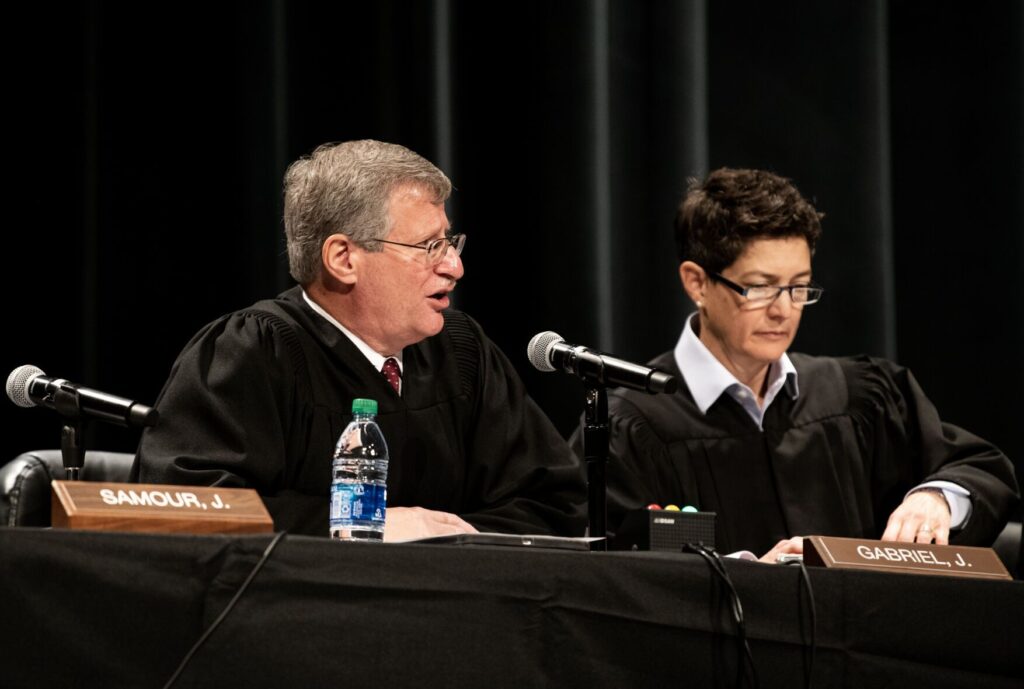

In response to a question from Colorado Politics, Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr., the chair of the committee that revises template jury instructions, said the committee occasionally receives feedback from judges and attorneys about language.

In 2023, the committee “received a comment from a member of the bar requesting that the recently modified reasonable doubt instruction expressly state that a reasonable doubt can be based on both the evidence presented or the lack of evidence presented,” he wrote in an email. “After discussing the request, the Committee voted to make the 2023 addition.”

The cases are People v. Schlehuber and People v. Melara.

Colorado Politics Must-Reads: