‘When the dust settles:’ Colorado stakeholders watch for major changes in national forests

“This is a typical bug-kill, blow-down mess that should have been harvested 20 years ago,” says Mark Morgan as he surveys a tract of lodgepole pine on a slope of national forest land west of Fort Collins.

Once his criteria is pointed out, it’s not hard to see why the forest is drawing the veteran logger’s frustration. Most of the trees are long dead from beetle infestation, lying where they fell. The trees that remain are sparse, unprotected. A matter of time before the full stand must regenerate from the ground up.

The scale of Colorado’s national forests — more than 13 million acres — is hard to wrap one’s head around. For a person like Morgan, who has been cutting trees on public land since he was a Colorado State University student in the 1970s, he tends to organize the forest into countless different trees stands: lodgepole, ponderosa pine, mixed conifers, riparian patches of aspen.

Bumping along logging roads he built and rebuilt over the decades, Morgan points out examples that start to blur together, but the philosophy of forest management gains some clarity. A lodgepole stand he once spent a summer cutting fenceposts from as a young man is now undergoing a fire mitigation clean-up. Most of it will be cleared, like other bare patches driven by.

“What is right silviculture for the land is not necessarily what is aesthetically pleasing,” he said, referring to the term for growing forests to harvest for wood products.

Morgan thinks about the forest as an asset in the long term, a perspective most involved with the public lands managed under the U.S. Forest Service they may have found hard to maintain in recent months.

Substantial changes to staff and policy under the administration of President Donald Trump have produced turmoil, as major agency heads have resigned or taken early retirement while the state of on-the-ground work remains murky.

One of the strongest indicators of the Trump administration’s position toward the country’s national forests so far, and perhaps the most pressing to a person like Morgan, may have come in the form of the Trump-signed executive order in March, “Immediate Expansion of American Timber Production.”

The answering USDA memo directs land management agencies to increase timber production on a wide swath of public lands.

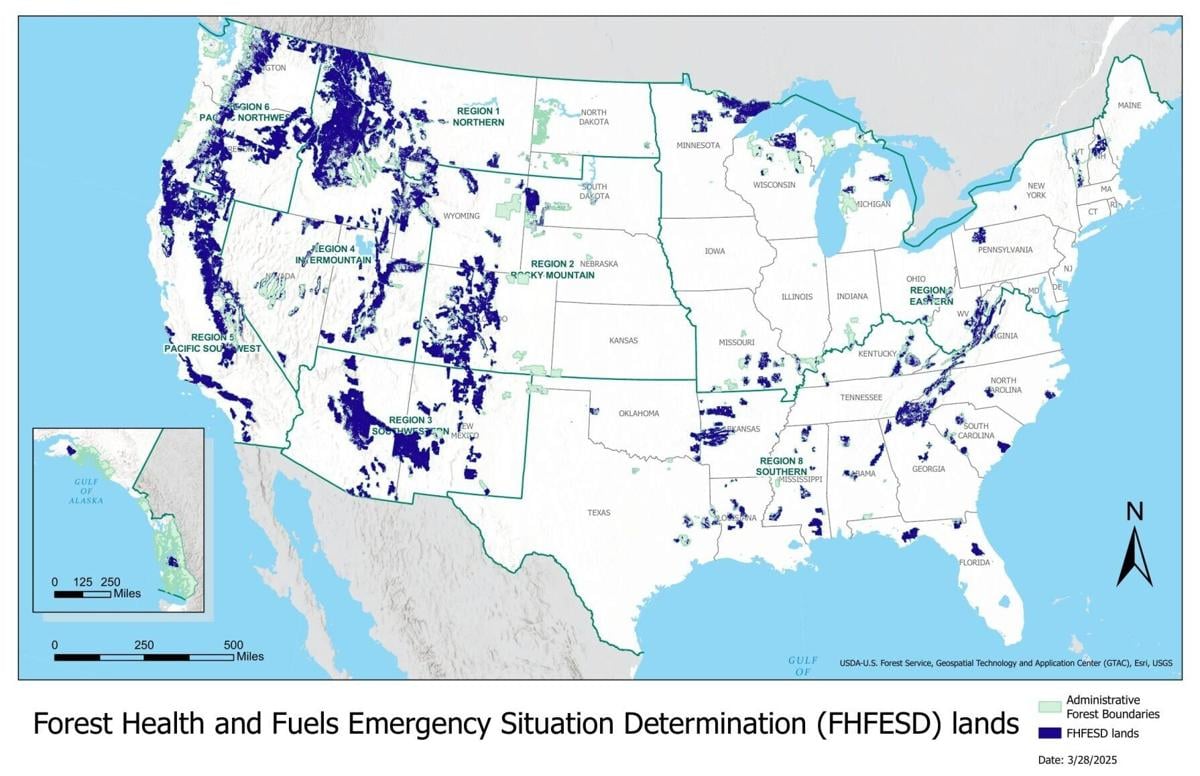

The map of areas covered by the executive order on logging could lead an observer to think major changes are ahead for the industry in Colorado. With an extensive wildland-urban interface, where forests at high wildfire risk are encroached by human development, much of Colorado fits the stated criteria.

Still, industry voices say the public shouldn’t expect major logging operations to crop up in its wake. Unlike the high-value timber in regions like the Pacific Northwest, Colorado has never had a robust timber industry.

“We’re not a timber state; we’re a stewardship state,” said Colorado State Forester Matt McCombs.

The logging order is one of many changes coming fast at Colorado’s public lands, leaving stakeholders to untangle both the near and long-term consequences.

Reduction in force

Other major changes to the Forest Service’s staffing and mission may be on the horizon.

In February, at least 90 Colorado Forest Service staff were fired from probationary positions in a mass email orchestrated by the Department of Government Efficiency, according to Gov. Jared Polis’ office. Those firings were contested in court, then halted by a ruling from the little-known Merit Systems Protection Board at the beginning of March for a period of 45 days.

At the same time, the U.S. Forest Service has not released information on how many employees may have taken the option of deferred resignation, leaving their positions but receiving pay and benefits until the fall. One of them was David Fitzwilliams, the supervisor of the White River National Forest. Russ Bacon, the supervisor of the Medicine Bow-Routt National Forests and Thunder Basin National Grasslands, has also announced his retirement.

The biggest changes may be ahead. The Forest Service is currently undergoing a reduction-in-force review that could result in thousands of firings and agency consolidation. U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, who oversees the Forest Service, said in March she would work with DOGE to “streamline inefficiencies across the Department.”

According to Politico, Trump also is separately considering an executive order to create a new federal firefighting agency, currently a key mission of the Forest Service.

Holding the line longer

Fighting a large-scale wildfire in Colorado shares some similarities with staging a war. In addition to the troops in action, the effort requires support and supplies to sustain people in the field, from portable toilets and showers to food services.

Historically, the responsibility has fallen to federal firefighters through the Forest Service to organize and deploy those resources, says Four Mile Fire Protection District Chief Chris Hawkins. He said the whole operation looks like a “mini-subdivision.”

“They bring a whole team,” said Hawkins. “Logistics and payroll and food services and laundry, everything you need to run a large incident.”

His district encompasses some of the most fire-prone areas in Teller County, surrounded by public lands under the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. A large-scale fire is, for him, an almost yearly event. A federal response can usually be expected within 48 hours.

Hawkins says the message this year from the federal government is to hold the line longer. A possible consolidation of incident response teams nationwide may delay deployment by a matter of days.

“What I’ve been told is we’re going to have to hold our own for three to five days, maybe seven,” he said.

The Forest Service recently announced a hiring period for up to 1,100 permanent firefighters and adjacent positions — 130 in the Rocky Mountain region. But Hawkins says the overall trend has been downward for firefighter staffing and resources in the federal lands near him, especially in the past year.

He said the changes have prompted a “ramp-up” in operational capability and equipment purchases for his district, which employs only three full-time firefighters in addition to 34 volunteers. He said a support effort for a large fire may be the domain of retirees and volunteers this season, as fire districts countywide divert most resources to the incident.

“We still have to run medical calls, we still have to run traffic accidents along with running a large incident. It’s going to be tough to do.”

Fire season

Firefighting may be the most visible mission of the U.S. Forest Service in Colorado. Each of the state’s three largest wildfires occurred in the past five years, while all of the top 20 have occurred since 2001, according to records from the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control.

The largest on record, the Cameron Peak fire of 2020, burned more than 200,000 acres of the Arapahoe and Roosevelt national forests. All three of 2020’s record-setting fires began on federal lands.

At the same time, the Forest Service has shifted its budgetary and staffing resources drastically in the past two decades into fighting wildfire. The firefighting portion of the agency’s budget passed the 50% mark in 2015, up from 16% at the end of the 20th century.

The employment cuts started in fall of last year with the announcement that the Forest Service would not be hiring seasonal workers and accelerated by the Trump administration’s firings in February were not officially meant to affect firefighters. They were exempted in the official statements on both actions.

The Forest Service has declined to provide detailed employment statistics on its firefighting force. In March, a spokesperson said that the Rocky Mountain region employs over 750 “permanent and temporary” wildland fire employees.

“We boost wildland firefighting capacity with other agency staff and administratively determined emergency workers who are qualified to support fire management activities,” a spokesperson wrote in an emailed statement.

About 75% of the agency’s staff are trained to respond to wildfires, according to Politico reporting, most of whom were not exempt from the staffing cuts.

Local fire chiefs like Hawkins say that leaner times must be upon his federal partners. He was hearing about reductions as high as 40% in lower-level firefighting positions like hand crew members, who set fire lines to contain spread.

“I think once we hit May, June — that’s when fire season really kicks off in the West,” said Hawkins. “We’ll see then how taxed we get as an industry, come those months. It’s going to be interesting, for sure.”

In the gap

Trump’s logging executive order may not entirely reflect Colorado’s timber industry realities, but trees do need to be cut — and at very large scale.

Loggers like Morgan take as many fire-mitigation and management contracts as they do commercial contracts. Colorado’s trees are low quality for construction purposes. At his mill outside of Fort Collins, Morgan chips or pulps a good portion of the material he removes. In some cases, he would rather just leave it on the ground.

While full operations like Morgan’s are rare, the appetite is high in Colorado for tree and vegetation removal. If left alone, a stand of lodgepole pine in the Roosevelt National Forest will grow thick — about 1,100 trees per acre, according to Morgan. The natural life cycle of the tree will then involve fire, promoting cones to drop and restart the stand.

Interrupted by human development, long-term fire suppression and beetle die-off, the lodgepole can no longer be allowed to follow this process in much of Colorado’s forests.

That’s especially the case when a watershed is involved, since forest management and the prevention of catastrophic wildfires can be vital to protecting waterways and infrastructure like reservoirs.

“We don’t grow trees in Colorado, we grow water,” said McCombs, the state forester.

To get the work of forest management done, the Forest Service relies on a patchwork of contracts with the state, private companies, and nongovernmental organizations like the National Forest Foundation and the National Wild Turkey Federation.

A big part of that work is through the Good Neighbor Authority, which allows the Forest Service to contract states with major fire-fuels projects. According to the Forest Service website, it currently contracts with the state in the White River and San Isabel national forests.

Implementation of the order could be years out, but McCombs is bracing for how changes to the Forest Service could impact the state’s involvement in public land management.

“We might be able to stand in the gap,” said McCombs.

Whether fire mitigation gets done is up to the contracting budget for the Forest Service, based on diminished overall funding this year.

“I think you’re going to see fewer of the service contracts,” said Megan Maxwell, executive director of the Colorado Timber Association.

She said Colorado’s existing timber industry is working under commercial capacity based on the availability of timber product in the state, but roadblocks exist to implementing Trump’s logging executive order in a meaningful way.

One of the major issues may be Forest Service staffing to identify projects and inspect sites, staffing that has already been reduced and could face another wave of cuts in the near future.

“Those are the types of people that the Forest Service is going to lose,” Maxwell said.

“We’re not exactly sure what things will look like when the dust settles,” said McCombs.

Stepping up

As confusion hits the agencies in charge of Colorado’s federal land, some of the nonprofits entrenched in national forests have been preparing to expand their missions.

The Colorado Fourteeners Initiative (CFI) was running out of 14,000-foot peaks in the state without routes maintained by the nonprofit by the time Loretta McElhiney, the organization’s longtime Forest Service liaison, retired last year.

With a pool of trail builders uniquely skilled to work in the high alpine, CFI has carved a niche within the state’s national forest system.

“Individual ranger districts aren’t doing projects on fourteeners because they know Colorado Fourteeners Initiative is there,” said Executive Director Lloyd Athearn.

Without sustainable maintenance, Athearn said that trails would naturally braid out and widen, disturbing fragile alpine environments under the boots of hikers.

“A big part of protecting those mountains is maintaining those trails,” said Athearn.

The CFI is one of a network of nonprofits heavily involved in trail maintenance and conservation in Colorado national forests. With the announcement that no new non-firefighting seasonal workers would be hired to the Forest Service in fall 2024, they are also the only stakeholders conducting trail work on some heavily trafficked routes this year.

While volunteer and private donations are up, Athearn said that the presence of the Forest Service has been withdrawing for longer than just the scope of the Trump administration.

“It seemed over the years there were just fewer agency people,” said Athearn.

Kim Gagnon, the director of marketing and communications for Volunteer Outdoor Colorado (VOC), said that her organization was also seeing an uptick in volunteer interest this year. With federal grant payouts still frozen from the Forest Service, she said VOC was looking at ways to balance its budget long-term without federal money as it continues projects in the national forests.

“If we need to step in any additional spaces, we will,” she said.

The Friends of the Dillon Ranger District runs a ranger-patrol program with 650 volunteers who greet visitors to one of the most popular parts of the White River National Forest, among other projects. Doozie Martin, the district executive director, said the nonprofit was trying to save space this year to be “more nimble” with its programming as Forest Service needs evolve.

Still, the nonprofits cannot do some of the work essential to managing public access to the forests. District volunteers cannot enforce Forest Service policies. And some jobs are not likely to attract volunteers.

“A bathroom-cleaning program would be a tough sell,” said Martin.

Lawmakers react

Since the February cuts, some members of Colorado’s congressional delegation have been critical.

“The USFS is already critically understaffed, and further employee cuts will have real and immediate consequences for Colorado’s economy, rural communities, and wildfire resilience,” wrote U.S. Sens. Michael Bennet and John Hickenlooper, and U.S. Reps. Joe Neguse, Brittany Pettersen and Jason Crow in a joint statement in February.

Last week, Neguse, a Democrat representing the 2nd Congressional District that includes four national forests, said that the “gutting” of the Forest Service would have real-world consequences on Colorado communities.

“To see the way in which this administration is gutting the federal workforce, not just, of course, with respect to the Forest Service, but the National Park Service [and] a variety of other agencies in the land-management context is unconscionable,” he said.

Not all have been in opposition to the direction of the Trump administration on federal lands. Republican U.S. Rep. Jeff Crank of Colorado Springs, who represents the 5th District, said he has “faith” that actions taken would make for a “more efficient and effective government.”

It remains to be seen whether the Forest Service under the Trump administration will alter or accelerate the management trajectory of Colorado’s national forests, which mean a livelihood to loggers like Morgan, iconic ski resorts in places like Vail and Breckenridge, essential grazing land for ranch operations, the West’s most important watersheds, and the hiking, biking, rafting, fishing and other draws to support the state’s $13.9 billion outdoor recreation industry.

But it’s certain to say the many stakeholders in the maintenance and use of Colorado’s forest wealth are watching closely.

“In this moment where it’s all hands on deck, we have moved into this mindset of shared stewardship,” said McCombs.