Colorado Supreme Court returns 3 cases to trial courts with instructions

The Colorado Supreme Court decided three appeals this month in ongoing civil and criminal cases, either overturning trial judges’ faulty decisions or providing clarification for further proceedings.

Although most of the Supreme Court’s decisions come at the conclusion of a case and after the Court of Appeals has rendered its ruling, the justices sometimes elect to immediately hear appeals from the trial courts when the standard appellate process does not provide adequate relief or the legal issues have significant public importance.

In its latest round of orders, the Supreme Court found a Denver judge required a plaintiff to disclose confidential information without the proper analysis, agreed an El Paso County defendant could inform the jury to a limited extent about his alleged victim’s prior sexual assault, and threw out a felony child abuse charge against a Jefferson County mother for lack of probable cause.

Privileged documents in class action suit

Jina Garcia filed suit nearly seven years ago against Centura Health but has yet to receive a trial. She is pursuing class action claims that the hospital operator improperly filed liens — claims against a person’s property to satisfy a debt — against people who have insurance, which Centura is obligated to bill first under Colorado law. Various appeals have delayed the case since it began in 2017.

Most recently, Centura requested certain documents and communications from Garcia, including her credit reports, insurance documents and any claims she made related to the automobile accident that landed her in the hospital. Centura argued the information was relevant to Garcia’s alleged injuries and the payment of her medical expenses.

FILE PHOTO

In January, Denver District Court Judge Andrew J. Luxen agreed Centura’s request fit in with “the ordinary type” of evidence in motor vehicle cases. Consequently, Garcia needed to provide Centura with the requested documentation. Garcia then appealed directly to the Supreme Court.

“The discovery ordered by the trial court seeks privileged, confidential and private medical, financial, attorney work product and attorney-client privileged information, which is irrelevant to the claims in this case,” her lawyers wrote.

Centura defended Luxen’s order, saying the information could disprove that its allegedly illegal lien harmed Garcia or other class members. Garcia responded that Colorado law is clear: If Centura created a lien and did it before billing her insurance, then it is liable.

“No other facts are relevant to the claims and defenses in this case,” her lawyers added.

In an unsigned, three-page order, the Supreme Court agreed Luxen misunderstood how to evaluate Centura’s request for information. It did not matter whether Centura was asking for the “typical” evidence of motor vehicle cases.

If Centura’s request is “relevant to the claims and defenses in this case,” the court wrote on May 17, then there need to be specific findings on multiple levels about whether to order the release of any confidential and private information. Even then, there will also need to be an evaluation of whether the evidence is “proportional to the needs” of the case.

The court vacated Luxen’s decision and ordered a correct analysis be done.

The case is Garcia v. Centura Health Corp.

‘Rape shield’ evidence

Joshua McFarland stands accused in El Paso County of sexual assault on a child. His attorneys have sought to introduce evidence of what the alleged victim revealed in her forensic interview: She was previously the victim of sexual assault by a different person, she participated in an interview at the time and law enforcement brought charges against that perpetrator.

Under Colorado’s “rape shield” law, evidence about a victim’s sexual history is generally inadmissible. However, there is an exception when the evidence is “relevant to a material issue” in the case. McFarland contended the victim’s references to the prior investigation would be confusing to a jury without some explanation, and her past experience with forensic interviews was also relevant.

FILE PHOTO: The Ralph L. Carr Judicial Center houses both the Colorado Supreme Court and the Colorado Court of Appeals as seen on Friday, March 1, 2024. The facility’s namesake is the former Colorado Governor, Ralph Lawrence Carr, who served between 1939 and 1943 and was known for his opposition to Japanese Interment camps during the time.

District Court Judge Marcus Henson permitted McFarland to use evidence of the prior sex assault in his trial, on the grounds that the victim “does bring it up, actually, a couple of different times” during her interview. He also believed the previous case was “context” for some adults’ reactions to the accusations against McFarland.

The Fourth Judicial District Attorney’s Office appealed directly to the Supreme Court, warning the evidence would actually be used to paint the victim as less credible because she had experience with being interviewed.

“Under this logic, a person can only be victimized once and maintain credibility. Under this logic, a person who suffers a subsequent sexual assault will always have their credibility tainted by the fact that they’ve already been through the investigative process,” wrote prosecutors. “This logic is not a circumstance that can be countenanced under the purposes of the Rape Shield Statute.”

The Supreme Court upheld Henson’s ruling in an unsigned May 17 order, while noting the contours of what the defense will be allowed to ask.

If jurors hear the videotaped interview, “defense inquiry that goes beyond what the victim herself referenced in her 2022 forensic interview will not be permitted,” the court wrote. “Accordingly, defense counsel may not inquire as to the specifics of the victim’s prior assault, including the charges brought in that case or its disposition, and may not attempt to demonstrate to the jury that the victim falsely reported her prior assault.”

The case is People v. McFarland.

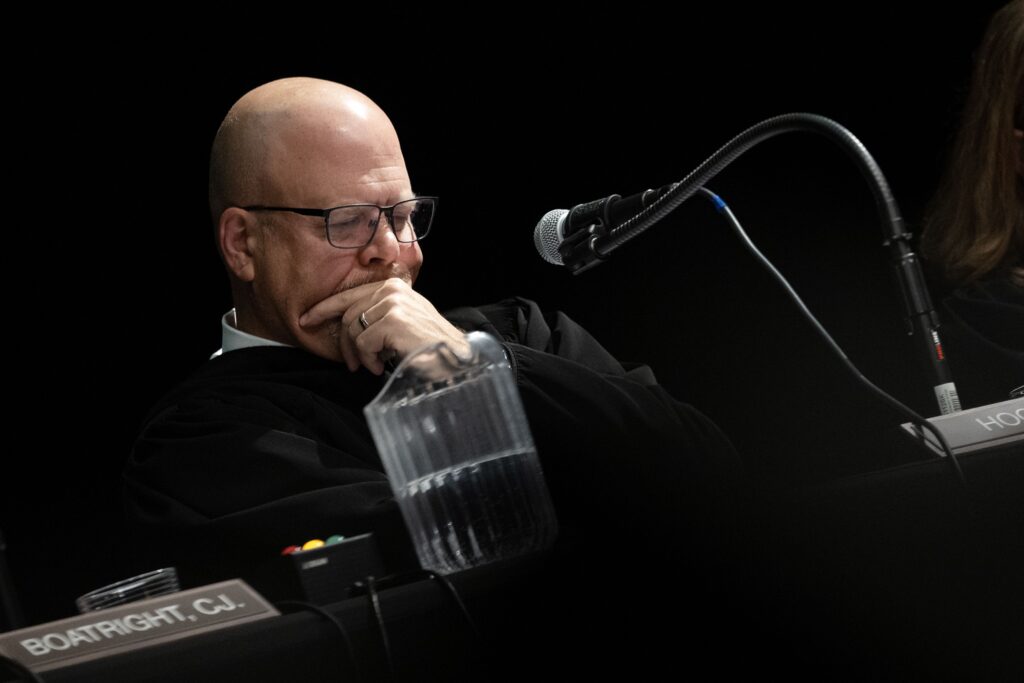

Deputy county attorney Rebecca P. Klymkowsky presents her oral argument to the justices of the Colorado Supreme Court in the County of Jefferson v. Beverly Stickle case during Courts in the Community on Thursday, Oct. 26, 2023, at Gateway High School in Aurora, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Insufficient evidence

Jefferson County prosecutors charged Kashia Dorsey with one felony count of child abuse resulting in death. Specifically, the prosecution contended she injured her 8-month-old baby or engaged in a pattern of conduct resulting in malnourishment, lack of proper medical care, cruel punishment, mistreatment or an accumulation of injuries to the deceased infant.

On Feb. 1, there was a preliminary hearing in which the prosecution argued probable cause existed to proceed to trial on the alleged offense.

“I’m going to tell the prosecution that this is a close call in my mind. I mean a very close call,” said County Court Judge Jennifer Melton before green-lighting the trial.

Dorsey immediately appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing Melton’s decision failed to analyze the elements of the crime. Moreover, Dorsey believed the prosecution had not presented any evidence about her “pattern of conduct.”

The Colorado Attorney General’s Office defended Melton’s ruling. It argued the evidence could show Dorsey, who had a prescription for the anxiety drug lorazepam, gave it to her child while the two were home alone. Alternatively, Dorsey’s own alleged impairment caused her to delay getting help for her ailing son, illustrating a pattern of conduct that resulted in the boy’s death.

Public defender Jessica Walker responded that neither of those points was reflected in Melton’s findings of probable cause.

“There was no evidence of any continued pattern of conduct, especially one that resulted in malnutrition, lack of proper medical care, cruel punishment, or mistreatment,” she argued.

The Supreme Court agreed with her.

“Even assuming the prosecution established probable cause that Ms. Dorsey committed some form of child abuse, the prosecution nevertheless failed to offer any evidence that the alleged abuse caused her child’s death (as required to prove the felony offense charged),” the court wrote in an unsigned May 20 order.

Because the proceedings had not established “any evidence of a causal link between Ms. Dorsey’s alleged child abuse and her child’s cause of death,” the Supreme Court vacated Melton’s finding of probable cause. The justices declined to say whether prosecutors might have probable cause of another, lesser charge for Dorsey.

The case is People v. Dorsey.