Weld County defendant need not turn over ‘all evidence’ of other suspect, Colorado justices rule

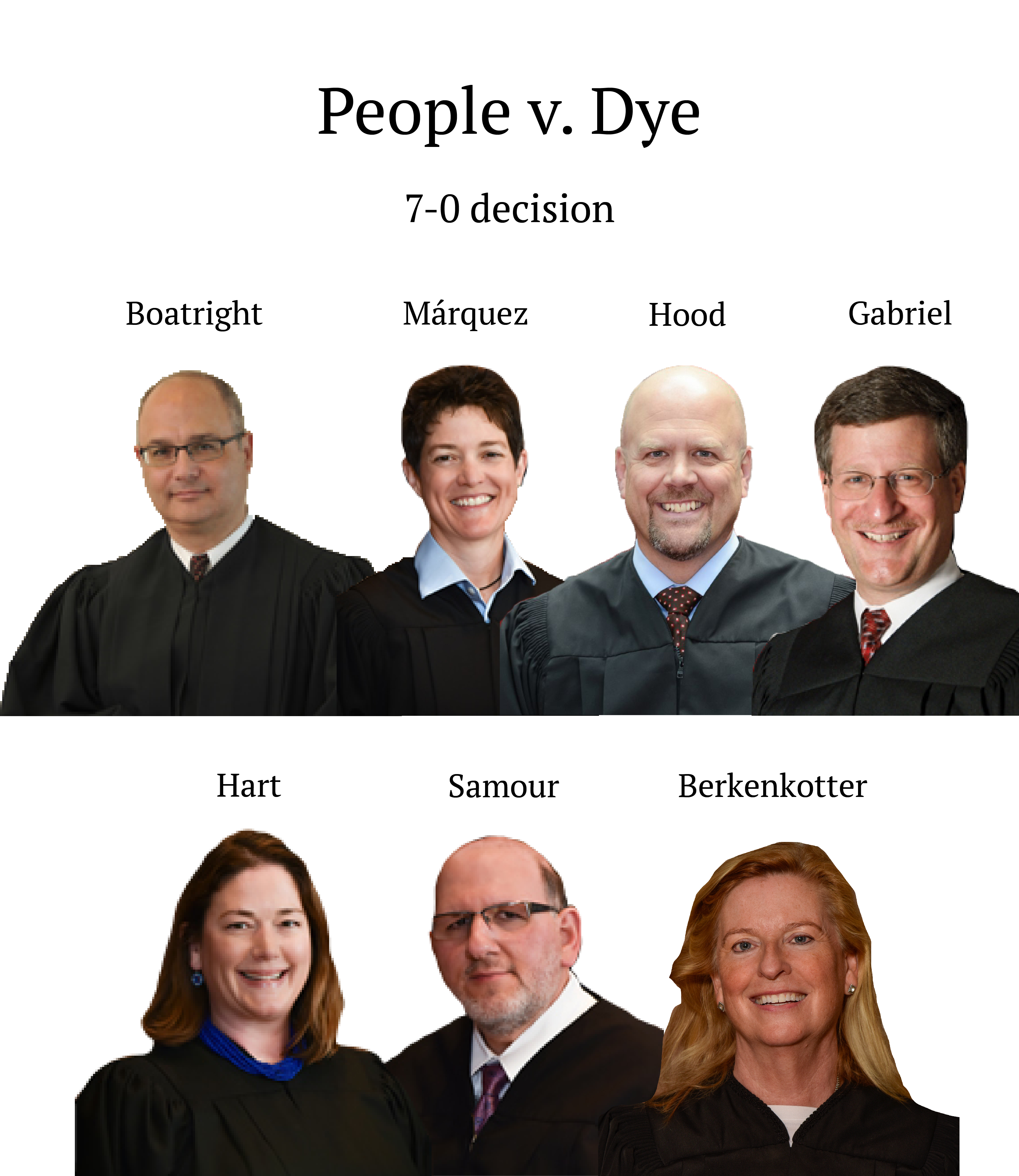

A Weld County judge went too far when he ordered the defendant in a murder case to reveal to the prosecution “all evidence” implicating another suspect, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Tuesday, while acknowledging some information-sharing is nonetheless appropriate.

For more than 40 years, the 1979 murder of Evelyn “Kay” Day in Greeley went unsolved. After a break in DNA evidence, law enforcement charged James Herman Dye of Wichita with Day’s killing in 2021. The defense, however, argued that someone else was the culprit – Day’s husband, Chuck, who law enforcement considered a main suspect for years.

The judge presiding over the case ordered Dye to disclose “all evidence” of the alternate suspect 45 days before trial, prompting Dye to appeal directly to the Supreme Court. Because it was the government’s responsibility to prove Dye guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, he argued, allowing prosecutors access to his evidence allegedly infringed upon Dye’s right to due process and other protections.

The Supreme Court declined to endorse Dye’s argument in its entirety, noting defendants do have the obligation to share certain details when they plan to claim an alternate suspect is the guilty party. However, an order to hand over “all evidence” is improper.

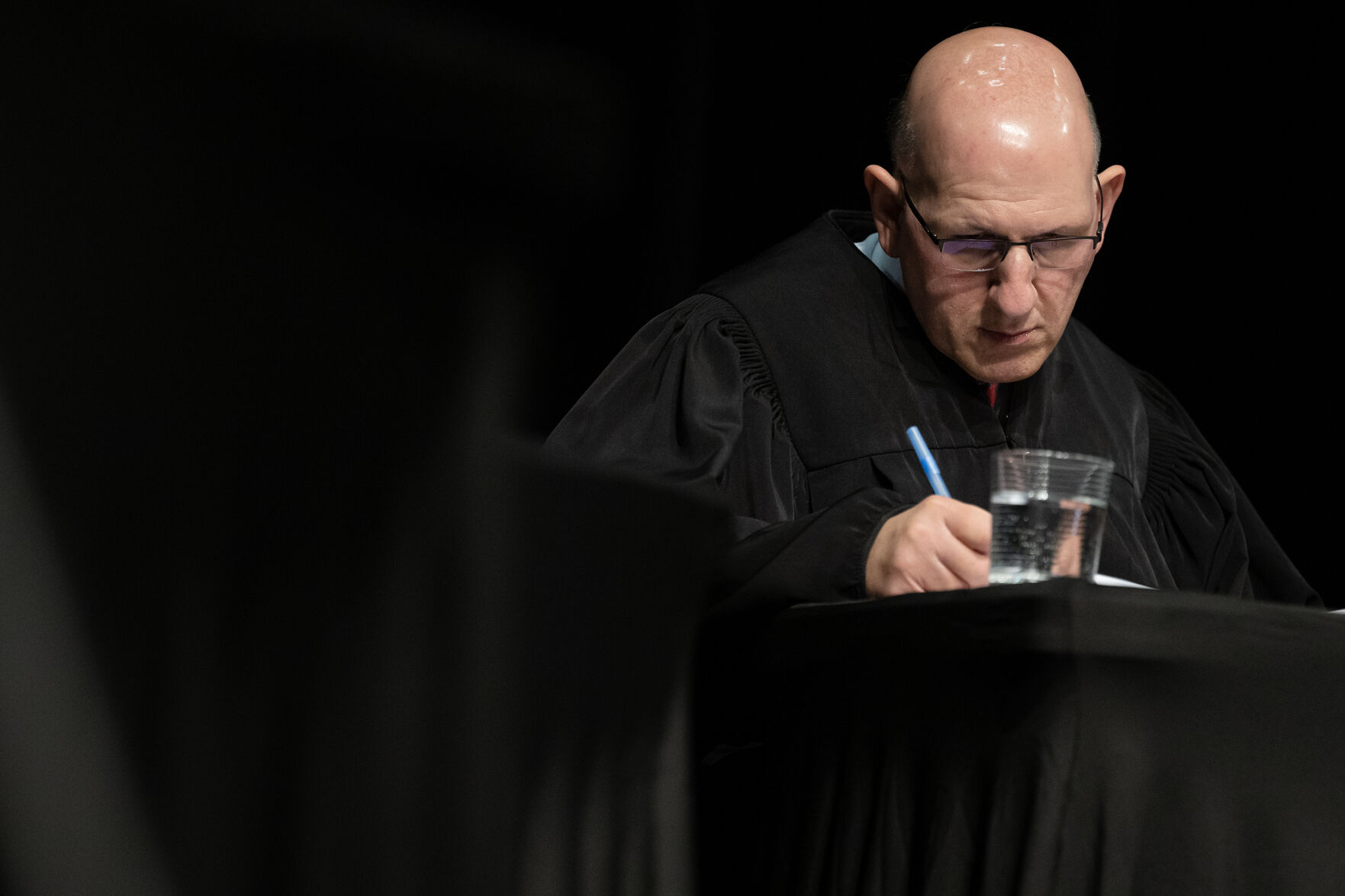

“A defendant must endorse the alternate suspect defense, identify any alternate suspects, and disclose the addresses of any alternate suspects who will be called to testify,” wrote Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. in the Jan. 16 opinion. “From there, it is up to the prosecution to conduct its own investigation into any alternate suspect.”

After Kay Day’s murder went unsolved for more than three decades, investigators linked Chuck Day’s DNA to her body in 2011. Subsequently, additional DNA and circumstantial evidence implicated Dye.

Awaiting Dye’s trial, Weld County prosecutors sought to force the defense to disclose any evidence of an alternate suspect – Chuck Day – on the grounds that they wanted to avoid an “ambush” at trial. Initially, District Court Judge Marcelo A. Kopcow observed the government was already “on notice” that the defense would try to shift culpability to Chuck Day.

However, in early 2023, Kopcow changed course and ordered Dye to “disclose all evidence” of an alternate suspect before trial. Appealing to the Supreme Court, Dye argued the requirement to “literally turn over his whole defense” violated his rights.

The Supreme Court ordered a response to Dye’s petition. The Colorado Attorney General’s Office, representing Kopcow, defended the decision, arguing judges need sufficient time to review alternate suspect evidence and determine if it is allowed.

The 19th Judicial District Attorney’s Office, meanwhile, attempted to reassure the Supreme Court there was no controversy after all. While judges need time to rule and prosecutors need to avoid ambushes, Kopcow’s order allegedly had little practical effect because it was clear to everyone what Dye would argue at trial.

“In fact, if Chuck Day remains the lone alternate suspect, as everything indicates he will, the district court’s order doesn’t require Defendant (to) turn over anything,” wrote Chief Deputy District Attorney Steve Wrenn.

The Supreme Court was not convinced.

“Even if Dye’s intention is to introduce alternate suspect evidence related solely to Chuck, there are live issues as to whether Dye must disclose that intention and make additional disclosures before trial,” pointed out Samour.

He elaborated that, in practice, the parties in a criminal case will all typically know before trial when an alternate suspect is in the mix. It is proper for judges to resolve evidence disputes before trial, Samour wrote, which may require the defense to disclose additional information about their alternate suspect.

What a trial judge may not do, he added, is “allow the prosecution to embark upon a fishing expedition.”

Because Kopcow’s order to disclose all evidence was “overbroad,” the Supreme Court overturned it.

The case is People v. Dye.