Q&A with Elizabeth Cadiz | Aurora’s chief public defender

The City of Aurora has been debating the future of its Public Defender’s Office, with council in recent months voting to send out a request for proposals to determine what the financial impact of privatizing the office would be.

The goal of the RFP is to determine if contracting out for public defense services and getting rid of the city’s in-house public defense office would save the city money, according to council.

Aurora Chief Public Defender Elizabeth Cadiz became the chief deputy of the office in 2017 and moved into the position of chief recently, when former chief Douglas Wilson retired.

Cadiz has attended several city council meetings to argue against the privatization of her office.

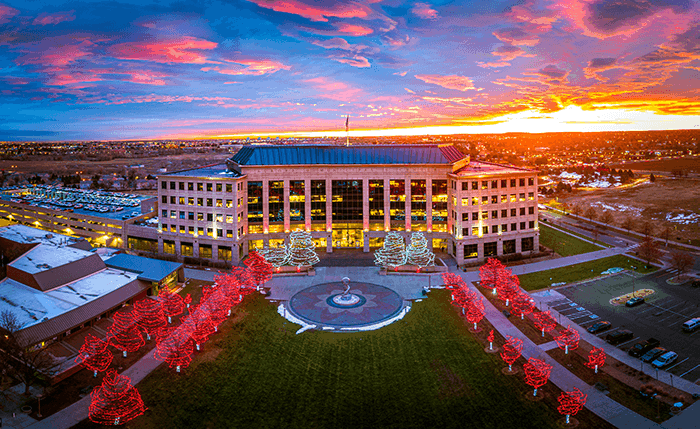

Aurora’s City Council established the office in 1989 and in-house public defenders have been serving Aurora’s indigent clients in the city since the new municipal court opened to the public in January 1990.

The Public Defender’s Commission was established in May 1992 to govern the office and “ensures that indigent clients are represented in accordance to its strict guidelines,” according to the city’s website.

Cadiz, two Aurora councilmembers and other officials identified numerous issues with the RFP at a recent council meeting, saying that – in its current form – it does not fully encompass the public defender’s role or the extra costs that come with privatization of the office.

Proponents of the RFP in its current form pushed for it to go forward so the council can get an analysis of the costs of privatization upon which to base a decision.

Privatizing the service would not get rid of access to a public defender for those who qualify, but would likely save the city money, said Councilmember Dustin Zvonek. He favors privatization.

The request is for qualified firms interested in contracting with the city to represent indigent people and will go out in early January, with proposals due back by the second week of February.

In March, staff will present findings to the council, at which time it will decide whether to move forward with privatization.

In a recent council meeting, councilmembers Alison Coombs and Crystal Murillo requested to add details to the RFP that account for some of the extra costs mentioned by guest speakers and those who wrote to the council.

The Denver Gazette sat down with Cadiz and Deputy Defender Griffin Desmarais to talk about their jobs, the cases they handle and their thoughts about privatization.

The conversation is as follows. Their responses have been edited for length and clarity.

The Denver Gazette: Tell me about your job? What does your day-to-day look like?

Elizabeth Cadiz: We’re tasked with representing every indigent defendant who qualifies. Either they’re in jail and unable to post bond or they’re out of jail and meet certain financial requirements. We represent individuals on offenses that carry a risk of jail.

There are three mandatory minimum sentences for motor vehicle theft, shoplifting over $300, and for a failure to appear in Aurora and we could be appointed on all of those kinds of cases.

Aurora is also one of five municipalities in the state that prosecutes domestic violence in municipal court. A large portion of our cases are domestic violence cases.

Griffin Desmarais: We go over cases with clients, discuss the options of taking a plea deal or taking the case to trial, discuss possible defenses and advise clients on what we think would be the best outcome for them.

We also represent people who have been accused of violating the terms of their probation or a suspended sentence. The vast majority of our cases are new offenses.

Cadiz: We’re bound by the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution, as well as a state statute and our ordinance, which requires that we give effective assistance.

For every case, we are ethically bound to ensure that individuals understand the charges against them, receive attention of mental health professionals if necessary, are competent to stand trial, and have an opportunity to review the discovery owed to them. We prepare and file necessary motions and litigate them. We also have an investigator who works for our office.

We ensure that the people we represent know that their choice to take a plea or not could carry collateral consequences, like immigration consequences, which a lot of our clients face. Even a municipal court conviction can result in things as serious as deportation.

We also do a lot behind the scenes not necessarily in the courtroom.

This year (2023), we handled approximately 4,100 cases.

We provide mental health screening and facilitate competency evaluations through contracts with Aurora Mental Health and with independent psychologists who conduct competency evaluations.

We do all of those things in addition to anything and everything you could possibly think of for helping clients, like directing them to resources to help them get clothes or food, find childcare when they’re expected to be in court, speaking to family members, etcetera. Our mission or vision is ‘advocate, protect and defend.’

Desmarais: Our caseload of clients is just one aspect of the of the job. While we’re prepping for trials and advising our clients, we are expected to also be available for those in-custody divisions every day of every week. We could be there for a few hours or all day.

Every afternoon, we have walk-in court for at least two hours, where we help people get set up for their next court date.

DG: How is your office structured?

Cadiz: We have the commission, which is responsible for the selection of the chief public defender and their assistants. As the chief, I have a group of direct reports, including two chief deputy public defenders who supervise teams of deputy public defenders and also have case loads of their own. We have an investigator, four administrative staff and a total of 20 employees.

DG: What would be the impact of privatizing/contracting out to replace your office? How do you feel about that?

Cadiz: There are lots of impacts.

Contracting out public defenders will be more expensive if it’s done right. If the representation provided in a contract, or some other way, is upholding the Sixth Amendment, then paying hourly for representation and on a case-by-case basis will add up.

With an institutional public defender’s office, instead of having five different groups doing the same work, you have one group in the courthouse. We have a system to efficiently accommodate the court’s docket. We can cover for each other when people go on leave. We plan for training together to ensure the representation being provided is at that constitutional level.

Privatizing would be a huge disturbance. The court and its processes have been built around the presence of an institutional public defender’s office. We’ve been part of the court since it opened its doors.

We’re often called down to the court for things that are not necessarily documented and we’re there as soon as we’re called. If you’re a private attorney and you’re off site or even if you’re on site, you aren’t really used to answering to the court in that way. It’s a different relationship.

The impact on our clients would be a detriment because, as city employees and as an institution, we’re committed to the future of our clients and to the day-to-day operations of the court. We have an interest in getting our clients the help they need to not come back again and in the reputation of the Aurora Municipal Court.

Desmarais: On a strictly personal level, and for lack of a better word, it sucks. Everyone who works here needs jobs and we love the jobs we have.

Our office has been here just as long as everyone else in this building. To be spoken about, not spoken to, about getting rid of our office is discomforting. We’re hearing about it, but it’s only affecting us and we’re still expected to do our jobs as normal for an unspecified amount of time.

Any attorney in charge of billing who bills by the hour knows how little sense this makes financially. I tried 25 cases to verdict this year alone. No private attorney is going to try 25 cases for the same or less than what I charged the city of Aurora being their employee.

Cadiz: This idea that a decision is being made about our office makes us feel as though we’re not important to that process. It gives a perception that we are kind of an optional addition to the court system.

We understand that this is a government operation and dollars and cents matter, but it’s shocking and hurtful that there wasn’t an empirical study or research-based conclusion or any allegation or concern around our processes before moving to this step. It feels disingenuous.

DG: How do you feel about the process City Council has taken on this issue?

Desmarais: This isn’t the first time this has attempted to be done, and there tends to be a pattern about when it comes up and why. We’re city employees just like everybody else and I’ve never heard any other department or group of employees in Aurora talked to or about in this way.

We experience some of the same prejudice our clients experience. To a lot of people, defendants are easy targets to ‘other’ and treat like they aren’t members of our community. As the people fortunate enough to represent them, we are lumped into the same category, as non-essential.

There have also been inconsistencies throughout this process. We’re told one thing, then suddenly the next time we hear about it, it’s not on the table anymore. It hasn’t been a transparent or clear process at all.

Cadiz: We are only here because the city wants to prosecute people and because the city chose to adopt ordinances where you can go to jail for up to a year.

It feels unfair and targeted. When this all started, there was a vote for a cost benefit analysis. We’re in the practice of representing people charged with crimes, so the benefits are kind of hard to identify. The cost benefit analysis was not completed.

Then, City Council said is wasn’t even going to entertain a study anymore, they were just going to move straight to sending out a request for proposal and that’s quite a jump.

Desmarais: When people have supported us or shared their opinions about the RFP, the general response is ‘we’re not making any decisions here, we’re just trying to see if this is going to make sense.’ But that’s not what a request for proposal is, it’s an intent to contract with anyone who’s willing to meet your requirements.

It’s also not fair to say they haven’t done anything yet because this whole process has been used to not give our office resources.

DG: How did you end up working in Aurora public defense? Why did you choose public defense over another type of legal work?

Desmarais: My first job at law school in Minnesota was working at a public defender’s office. I got certified as a student attorney, where I could appear in court and helped run the in-custody division in a county there.

I think I always knew I wanted to be in the courtroom and that I wanted to help people. I’ve always had a ‘stick up for the little guy’ mentality and felt this was the best way to do that and work by my morals.

Cadiz: I’m from Kentucky and was raised in a very Catholic family. My grandparents were from a tiny town where there were a lot of poor people and they were very active in the church and in bringing support out to people who were in some pretty tough spots.

One summer I went with my grandparents to a couple living in a small house in need of repair. I remember feeling a little scared as to where we were and going inside and just feeling thrust into the setting of someone much less fortunate than me.

It was awkward and difficult. The woman asked if I wanted some lemonade and I said no, but my grandmother elbowed me saying ‘take the lemonade.’ I remember thinking about how incredible it was to watch someone with that level of compassion who had endured all this pain and suffering.

As I went through school, I was interested in the people in our communities for whom it would be more comfortable for majority of people not to think about.

I was always drawn to that. In my early days as a public defender, I would get lost in interviews just listening to my clients’ stories and thinking to myself ‘how is it that I’m sitting here and you’re sitting there? What happened?’

There’s reward in advocating for somebody in times where you may be their only voice and their only protection. It’s empowering. It’s emotional.

DG: What sets public defenders apart from other lawyers (in terms of skillset, education, etc.)?

Desmarais: We’re appointed based on an individual’s income. We see so many different kinds of people. People who are students, people who have been struggling with homelessness, people who have worked every day of their life, but unfortunately lost their jobs. There’s a lot of reasons why someone in that moment when you meet them may qualify for public defense.

We aren’t dictating the clients or types of cases we want to take. We take every single case in which an individual qualifies, so I think we have to have thicker skin than some other professions. We have adaptability and we’ll be there for people who are oftentimes in the worst spot they’ve ever been in.

Cadiz: Not everybody knows that a statement they made to the police could be used against them. There’s so much education that goes on in our jobs and we have to figure out the best way to do that, which is a unique skillset.

The choice to take a case or go to trial doesn’t come down to a fee agreement for us. There’s a humanity aspect that is foreign to many attorneys.

DG: How do cases your office handles differ from cases seen by other lawyers?

Desmarais: A lot of our cases aren’t high profile, it’s everyday people in situations that I think any of us could potentially see ourselves in.

The vast majority of the time it’s just people struggling and making decisions or being accused of making decisions to feed themselves, clothe themselves or get out of the cold.

Cadiz: There are over 215 municipal courts in the state. Only five have city attorneys who prosecute domestic violence.

Last year, the state tried to remove that jurisdiction and our court was vocal about keeping it, expressing that, unlike small municipal courts around the state, we’re a full service court and should be treated as such.

We hear a lot that this court operates more like a county court. Well, county courts have a public defender. And the reason they have a public defender is because public defenders are more efficient and have better representation.

DG: What makes Aurora’s municipal court system/the cases Aurora sees different from other big cities like Denver and Colorado Springs?

Cadiz: Colorado Springs is a good example of a municipal court that does not prosecute domestic violence, does not have mandatory minimum sentences and does not try cases at the rate we do.

Colorado Springs might appear to be comparable because of its size, but not every city has the same size municipal court relative to the size of the city. Really, the only comparable within reach would be Denver.

Desmarais: The combination of mandatory minimums and the desire to keep cases here versus sending them off to county or district court make Aurora unique.

Something I had no idea occurred before I got here was that in municipal court, specifically in Aurora, police officers are the ones making charging decisions. There’s no city attorney or prosecutor reviewing the officer’s reports and deciding which cases should proceed.

Having officers trying to divert cases here more than they otherwise would and the fact that there’s no oversight, filtering out cases likely to be unsuccessful, is part of why we try 123-plus cases a year. A number of those cases probably had no business being prosecuted in the first place.

Cadiz: For a city whose express priority is tough on crime, it doesn’t serve their interests to have a strong and effective defender. This is just what I believe can be suggested by the timeline, that it would be easier to have a group of attorneys who, like in Colorado Springs, take a flat fee and come in and stay until noon and plea everyone out.

We’re never going to be that. Over the years when we are at our strongest, we have faced many threats to our independence and to our existence and I think this is just another one of those times unfortunately.