Q&A: Looking ahead to paramedics’ trial for Elijah McClain’s death

The third and final criminal trial over Elijah McClain’s 2019 death in Aurora is scheduled to begin next week after a jury is chosen.

Two paramedics from Aurora Fire Rescue, Peter Cichuniec and Jeremy Cooper, face charges in connection with their decision to inject McClain with 500 milligrams of the sedative ketamine after a struggle with police officers that lasted nearly 20 minutes. Within a few minutes of receiving the injection, McClain stopped breathing and went into cardiac arrest.

The trials of three Aurora police officers, for accusations their restraint of McClain made him more vulnerable to the ketamine, ended with one convicted of criminally negligent homicide and third-degree assault, and the other two acquitted of all charges.

Police officers described McClain during the struggle as showing extreme strength and “on something.”

Aurora police officer Randy Roedema told investigators McClain attempted to grab the gun of Jason Rosenblatt, another officer on the scene. Roedema was found guilty last month of criminally negligent homicide and third-degree assault in McClain’s death. The same jury found Rosenblatt not guilty on manslaughter and assault charges. Officer Nathan Woodyard was acquitted of all charges and has been re-instated to active duty.

The cases against the paramedics accuse them of making the decision to administer the ketamine to McClain without speaking to him or examining him firsthand. Cooper made the injection, according to the indictment, and Cichuniec is charged under a theory of complicity to Cooper’s actions.

Both paramedics face charges of reckless manslaughter, criminally negligent homicide, and multiple counts each of second-degree assault. They’ve pleaded not guilty.

Defense attorneys for the police officers who went on trial also sought to lay blame squarely on the paramedics for McClain’s death.

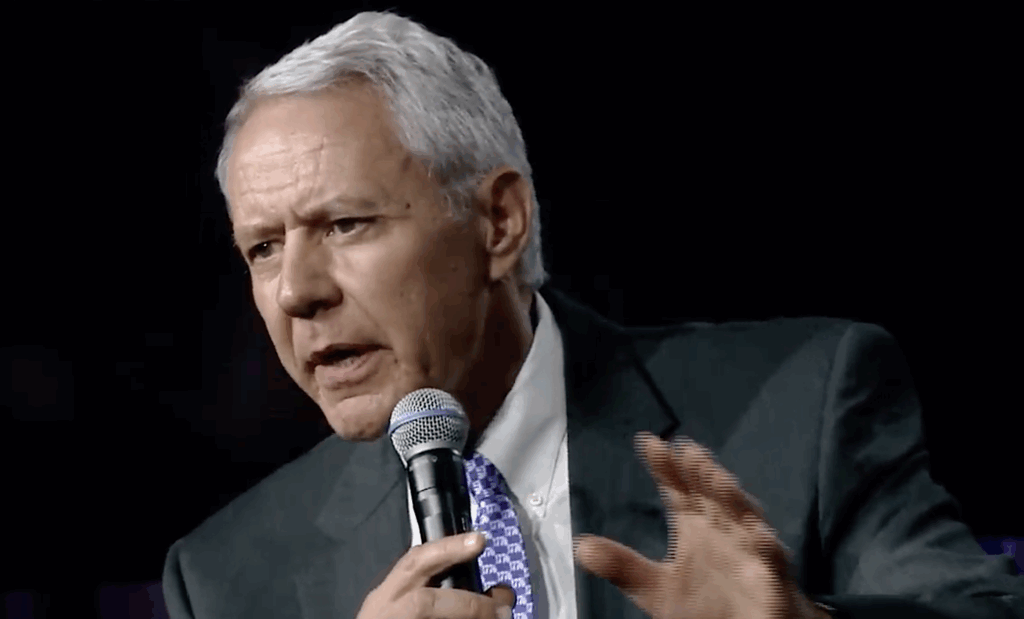

The Denver Gazette spoke to Stan Garnett, a former district attorney for Boulder County and co-founder of Garnett Powell Maximon Barlow, about why criminal charges against medical professionals are rare – and risky, he believes.

Aurora police officer not guilty on all charges in Elijah McClain death

Stan Garnett: I’m not aware of a similar case anywhere in the country. But I do think it’s unusual, and potentially not advisable, to criminalize mistakes made by medical professionals. In other words, it happens all the time that paramedics or doctors or nurses make an unintentional mistake in amount of medication or other issues that maybe has a tragic result.

But certainly given the pressure that paramedics are under when they arrive at a scene like this, and they’re getting information from police officers, it is certainly unusual to prosecute them criminally for a tragic result. In the other trials, it sounds like those defendants attempted to blame the paramedics, but from what I can understand they were blaming them in a causation fashion, saying it was the ketamine that killed the victim.

But in the trial of those paramedics, it will all be about mental state. I anticipate it will not be about whether they use the right amount of ketamine or not, because I assume that’s going to be pretty easily determined by the jury. The issue is going to be simply: Did these paramedics intend any harm? Or did they simply make a mistake? And that’s what I think the whole thing will revolve around. And it will be interesting to see how the jury resolves that.

The Denver Gazette: My reading from hearing these cases so far is that the prosecutors are going to be arguing that this was not a mistake – it wasn’t just that the (ketamine) dose was too big; it was that they made the decision to inject Elijah McClain with ketamine based only on the word of police officers; and, they didn’t do anything to assess him themselves.

Garnett: The prosecution is probably going to make this feel like a medical malpractice case, where they’re going to say these are highly trained professionals. They know what to do. They shouldn’t make mistakes. The problem is, it’s a criminal case. And so they’re going to have to prove (intent).

You’re dealing with reckless manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide, which will require the jury determining that there was some level of harm intended towards the victim. And that’s what the jury is going to analyze.

In other words, it’s one thing to say you should have paid more attention; you could have been more careful; you should have followed a different protocol. And it’s another thing to say you committed a felony manslaughter here because you were so reckless, and that’s what it’s all going to be about in the case.

I’ve tried around 200 jury trials and several hundred non-jury trials in my career. What you see when you have multiple trials over the same fact pattern is you have everybody pointing the finger at whoever’s not in the courtroom. And it won’t surprise me if the paramedics’ lawyers blame this all on the officers who have already been tried, and of course, they’re not going to be able to be there to defend themselves.

The concern I have, as a lawyer who watches these things, is we should be very careful about situations in which mistakes by medical professionals are criminalized. And whether this is a case where that’s appropriate or not will be determined on the facts and the jury.

Officer claims he thought his life was in danger during McClain struggle

DG: Can you talk a little bit more about why that is such a fraught area?

Garnett: We want medical professionals, especially in emergent situations, to be able to make judgment calls and not to become paralyzed about the possibility that if they make a mistake, somebody in hindsight four years later is going to say that was a criminal act that you’ve committed.

And that’s what I think is at play, particularly when you’re dealing with paramedics who have training and are in many respects highly skilled and skilled at dealing with emergency situations. But they’re not doctors, and they’re moving from one crisis to another. You want them knowing that their judgment will be respected in most situations. And again, this case may be the exception.

DG: Do you have any gut instincts about why the juries might have come to the conclusion they did in these trials that we’ve already had?

Garnett: Obviously, this is a very tragic situation. And anyone who learns about it, whether in court or anywhere else, has got to feel empathy for Elijah McClain (and) his family. But there’s a big distinction between a tragedy and a crime. And so I think what it reflects is the jury paying very close attention and trying to be fair in trying to come up with a resolution in both trials that’s just to everybody involved. And that, in their mind, meant not guilty with Nathan Woodyard, and the split verdict in the other case.

DG: Prosecutors decided, I want to say it was midway through the first trial, not to hinge their case on the legality of the stop in the first place. But if that had been an issue that prosecutors ultimately tried to hinge their case on, do you think the question of whether the stop was legal could have changed or influenced the outcome of the officers’ cases?

Garnett: I think that’s a very fair question. But I doubt it. And the reason is because although the decision to stop Mr. McClain by the officers was sort of part of a chain of events, it would be extremely attenuated to suggest that decision, if it was incorrect, somehow created the kind of mental state necessary for a homicide charge.

These are challenging cases to prosecute, and I have no doubt that they’ve done the best they can do, but they have to focus on what is going to make a difference in the mind of the jury.

The level of probable cause or suspicion needed for a stop is quite low under the law. And the reason for that is because you want officers to be able to investigate circumstances that are concerning. Somebody called in and said there’s a suspicious person. It’s in the interest of public safety that when a call like that comes in, the police can do what they need to do to investigate.