Experts: Denver schools show ‘irrefutable’ pattern against abiding by transparency laws | ANALYSIS

An illegal executive session – requested by Denver Public Schools Superintendent Alex Marrero and exposed after a media coalition successfully sued in court – appears to unsheathe the tone for a calculated pattern aimed at skirting Colorado’s open meeting and public information laws, attorneys and supporters of open access to government say.

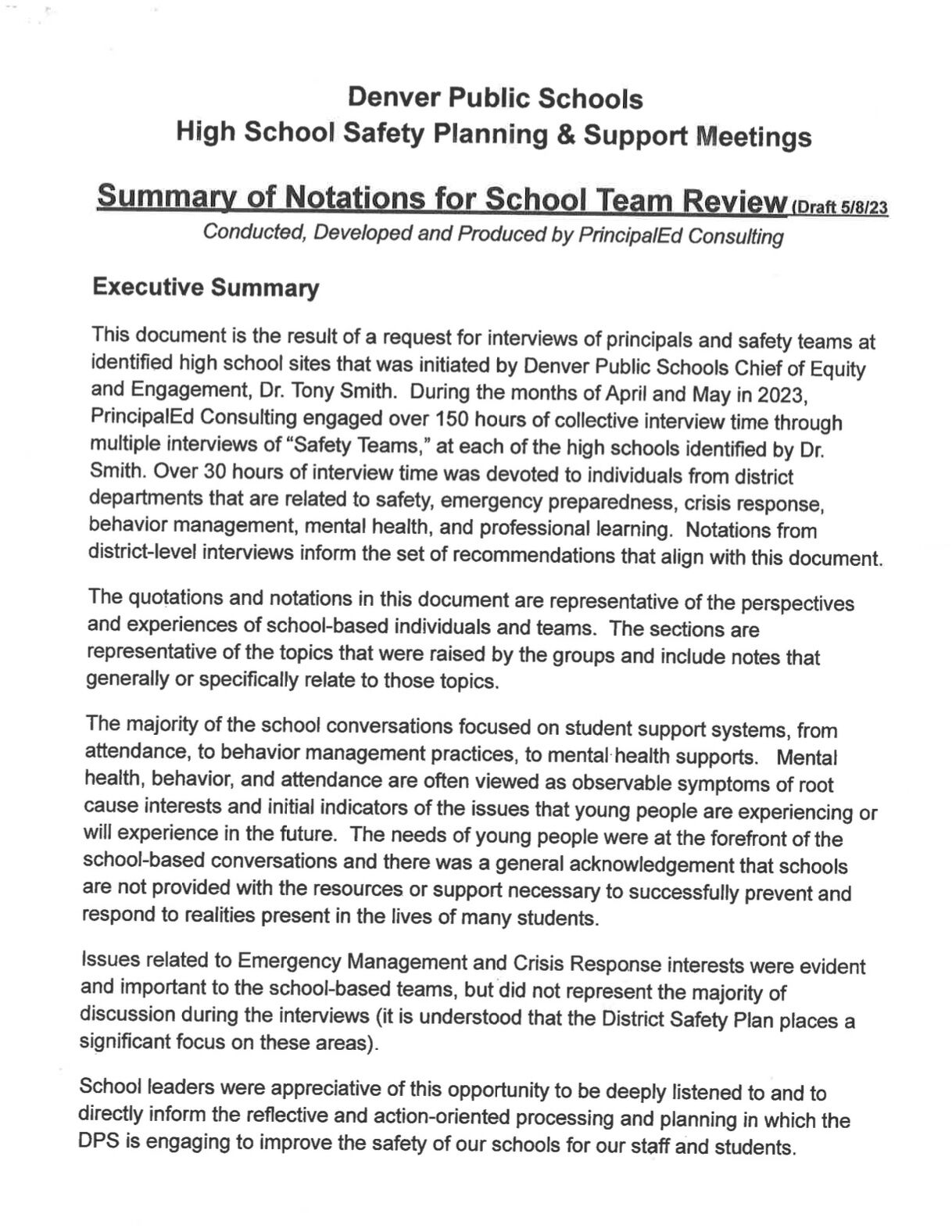

The latest attempt to shield the district’s inner workings from the public came in the form of a safety report by John Youngquist, president of PrincipalEd Consulting, at the request of Deputy Superintendent Tony Smith.

District officials declined to release the final report.

“This is not an isolated incident,” said Steve Zansberg, a First Amendment attorney and president of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition. “I think it’s irrefutable that there is a pattern of conduct that the district has not abided by the state’s transparency laws.”

Formed in 1987, the coalition promotes press freedom and open access to government.

Zansberg is a prominent media attorney who has represented a number of Colorado news outlets, including The Denver Gazette, in a recent legal challenge seeking records of the the district’s March 23 executive session. A judge sided with the coalition and ordered the district to release the recording. District officials were appealing the court’s decision when the board voted unanimously to release it, effectively ending the legal battle.

Will Trachman, a constitutional rights attorney who has been on both sides of the Colorado Open Records Act (CORA) as a requester and as a custodian of records, agreed, saying the district’s responses “seem calculated.”

“It doesn’t seem like it’s a legitimate assertion of privilege,” Trachman said.

Trachman added, “I do think it does indicate some willfulness.”

Trachman has previously served in the U.S. Department of Education as deputy assistant secretary in the Office for Civil Rights and as general counsel for the Douglas County School District.

Board President Xóchitl Gaytán disagreed with the assessment.

“I don’t know that I share the same concern at the moment,” Gaytán said.

Gaytán, who was previously unaware of the report, also challenged the notion that the district’s missteps – from the illegal executive session to CORA roadblocks, such as requiring “magic language” to charging exorbitant fees – could play in to the public’s perception of lack of transparency at Denver schools’ governing body.

Earlier this month, The Denver Gazette’s news partner 9News obtained an 11-page copy of a draft summary report.

The full report is roughly 30 pages and contains recommendations for the district.

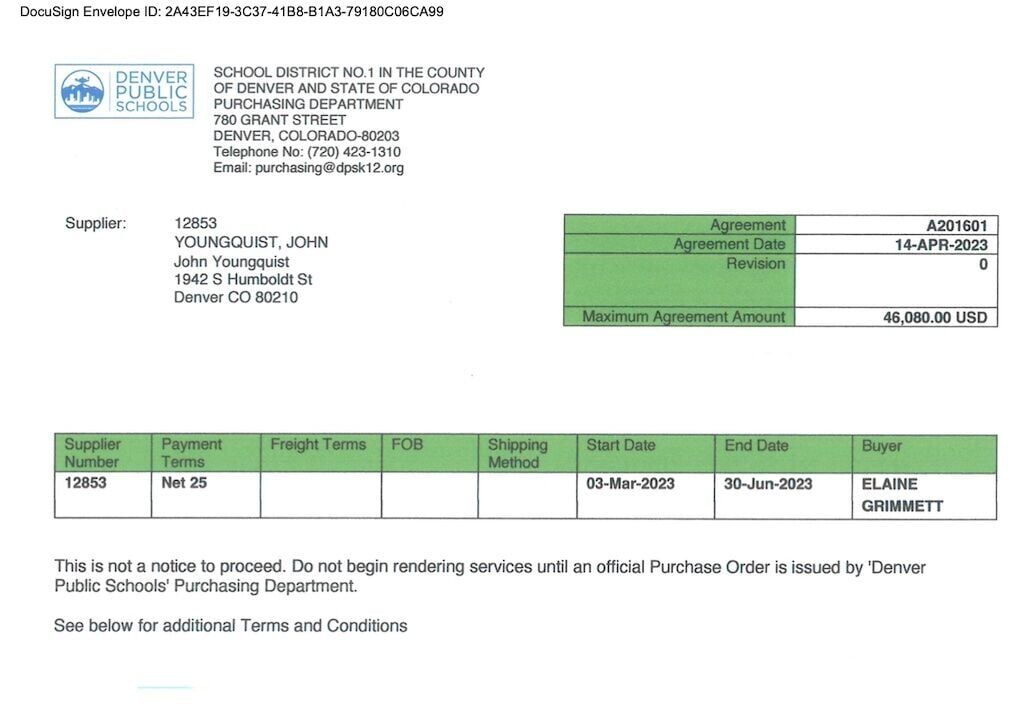

The Denver Gazette, and other media outlets, requested, under the state’s records laws, a copy of the Youngquist report, as well as the contract, which was signed roughly three weeks after two East High School administrators were shot and wounded on March 22. Police said 17-year-old Austin Lyle, whom they accused of shooting the administrators, later committed suicide.

Transparency and campus safety are issues that have roiled public sentiment in the months since.

Stacy Wheeler, the district’s records custodian, provided the contract, but she withheld the safety report, citing attorney-client privilege.

The contract amount was $46,080.

Wheeler did not respond to multiple requests seeking clarity on which attorneys may have been involved in contracting the report and why.

The district has not explained – given that neither Youngquist nor Smith is an attorney – the grounds for which to claim attorney client privilege.

According to the contract, Youngquist was hired to, among other things, audit the emergency management and crisis response protocols for 11 of the district’s high schools, including East.

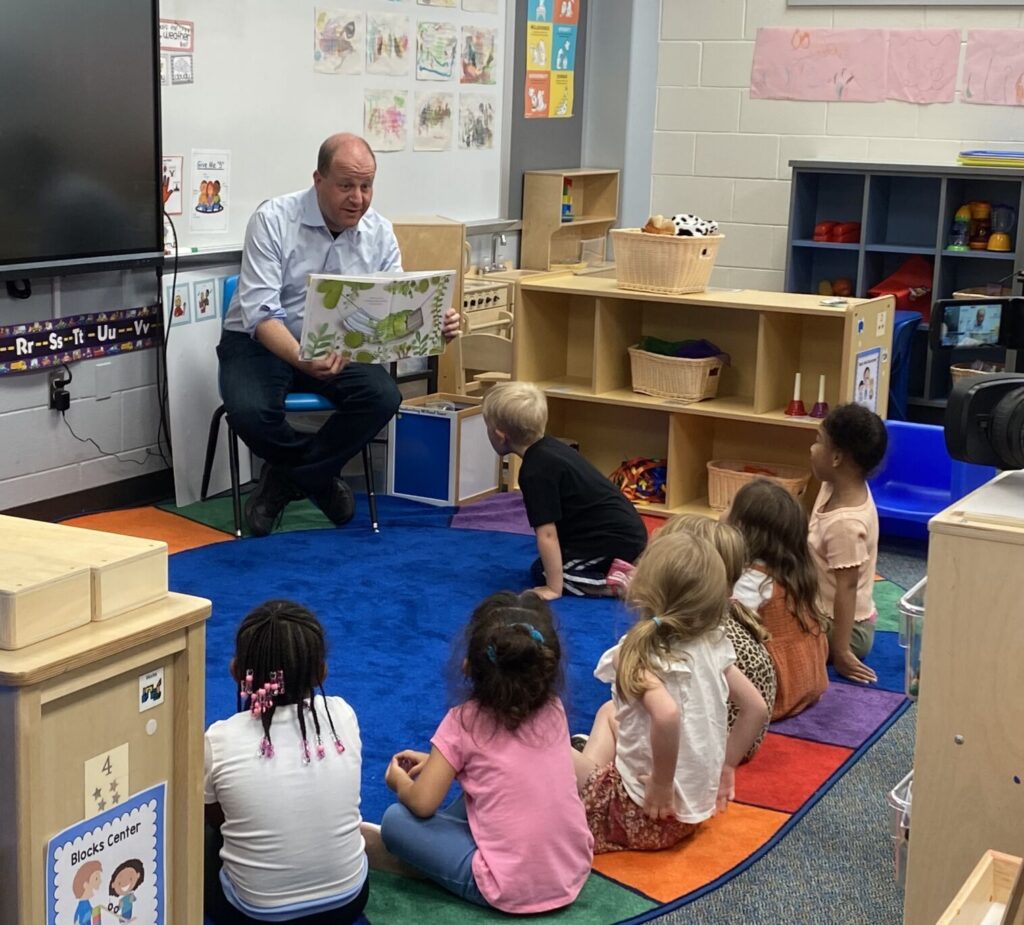

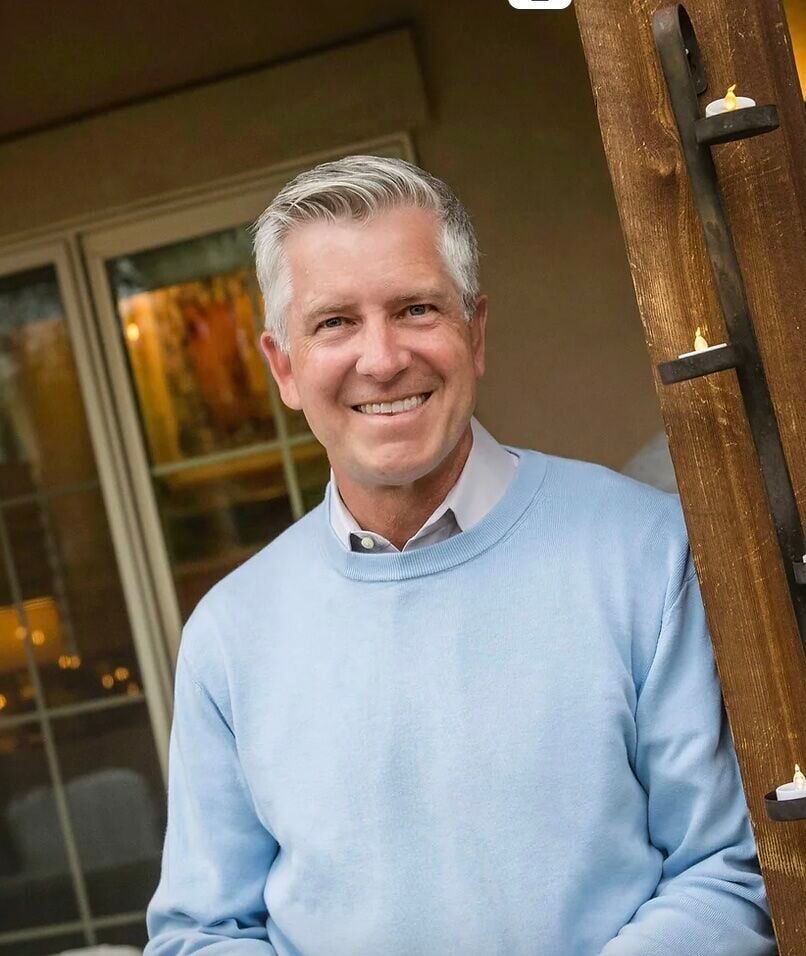

Youngquist, who is a former East High School principal, is running for the at-large seat being vacated by Board Vice President Auon’tai M. Anderson.

He declined to discuss the report, citing a confidentiality agreement with the district.

Youngquist – who has campaigned on “restoring transparency” – said that, if elected, he would prioritize addressing in the first three months the district’s responsiveness to public records requests.

“It creates, absolutely, a lack of trust and makes you question the integrity of an organization and its leadership that keeps doors shut,” Youngquist said.

Youngquist added, “We need to be a high trust organization and when we’re hiding information, that creates a context of low trust and low integrity. And that is not how a school district is supposed to be run.”

The district’s decision to shield the Youngquist report from public view seems to align with a pattern by the district to – as one expert put it – delay and obfuscate as the response to request for records.

In the weeks after two East High School deans were shot, when the public was demanding answers, The Denver Gazette submitted 32 requests over the past six months for public information under the Colorado Open Records Act to shed light on the district’s response. In response, district officials not only delayed, denied and obfuscated, they also used fees as a deterrent, according to experts, citing, among other experiences, The Denver Gazette’s quest to obtain public records.

“We see a lot of effort by Denver Public Schools to withhold records that we think should be public records,” said Jeff Roberts, executive director of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition.

Roberts added, “In Colorado, the only way to legally challenge a denial of public records is to go to court.”

luige.delpuerto@gazette.com