Report: Dozens of Native American children died at Colorado boarding schools

A Colorado General Assembly-commissioned report on the history of Native American boarding schools concluded that dozens of the children entrusted to those schools died under their care.

Many more children faced psychological or physical abuse, including sexual abuse, according to the report.

The report, under the direction of Dr. Holly Kathryn Norton, the state archaeologist with History Colorado, hints that there is much more that should be looked at, but the short timeline dictated by the legislature meant some things just didn’t get done – and some things the legislature asked for shouldn’t be done at all.

House Bill 22-1327 went into effect on June 1, 2022 with a deadline for a final report of June 30, 2023.

The final report, 139 pages, was released this week by History Colorado, although tribal representatives and the Colorado Commission on Indian Affairs were given copies back in June.

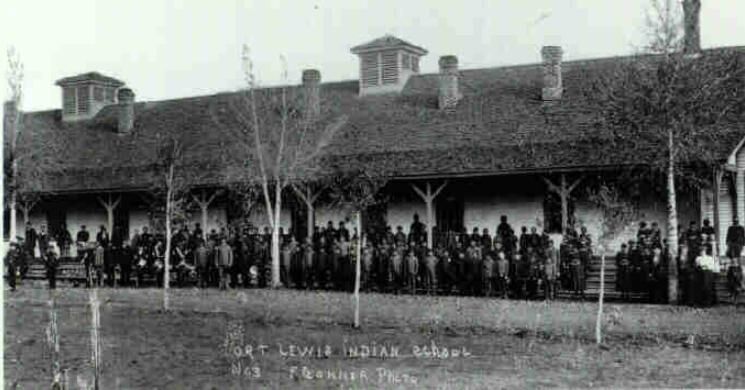

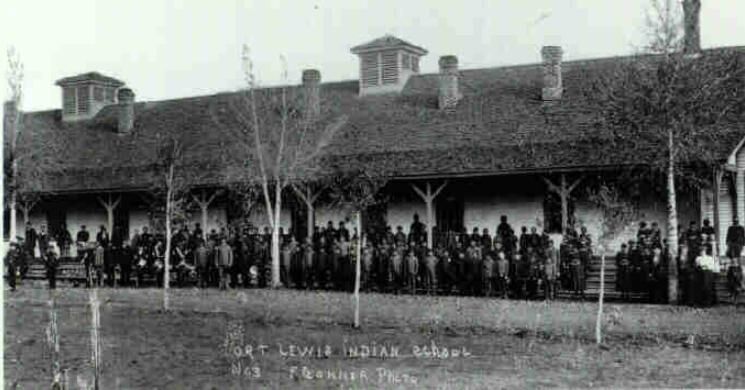

HB 1327 gave History Colorado a list of research projects, beginning with events, abuse, and deaths that occurred at the federal Native American boarding school at Fort Lewis, which was located in nearby Hesperus and operated from 1880 to 1911. The report noted eight different schools that had Native American students between 1880 and 1920, but focused primarily on Fort Lewis and the Grand Junction Indian Boarding School, also known as the Teller Institute, which operated from 1888 to 1911.

The projects included identifying and mapping graves of Native American students at Fort Lewis and “off-campus cemeteries,” to research “Native American student victims” at Fort Lewis, and to review written and recorded history, including oral history, that described the experience and trauma of students who attended Fort Lewis, as well as their families.

The latter task was the one that was the most difficult to complete, the report noted.

The history of the Fort Lewis boarding school was not recorded by students or their families, so researchers had to rely on government reports sent by the superintendents, which often presented only the best light, or contemporary newspaper accounts.

The report noted, for example, that the almost complete autonomy by superintendents meant they “were able to weave their own narratives about the everyday experiences of students under their care, and indeed we see those stories pushed forward to Washington. Superintendents used these letters and the distance from DC to conceal internal issues except the ones they wanted to bring to the attention of Washington.”

As for oral histories, the report said that wasn’t doable.

“Given the short time frame” for the report, and “the need to intentionally approach oral history interviews from a perspective grounded in knowledge of the history of schools in Colorado, cultural sensitivity, and trauma-informed approaches, it was not a directive that could be accomplished responsibly this state fiscal year,” the report said.

The report also asked why the state government needed the oral histories at all. Since the two main schools researched for the report – Fort Lewis and the Teller Institute – had both closed by 1911, there are few, if any living survivors of the schools, the report said. In addition, family members of the survivors said their relatives did not speak of the experience.

“Oral histories should be first hand accounts of survivors … I would caution that oral histories must serve a greater purpose than simply recording the trauma of already victimized people, who do not owe the state their emotions or stories,” the report said.

In all, the two boarding schools enrolled students from 22 tribes, the report said.

More than 65 students died at the two schools, the report said, ranging in age from 5 (which was too young to even have been enrolled at the school) to 22, which the federal government said was too old to be enrolled. The reports sent to Washington never identified the name or even the tribal affiliation of children who died; they were often referred to instead as an “Indian child.”

“There is no threshold where the death of children at the boarding schools is acceptable,” the report said. “Every single death was a tragedy to the families who lost their loved ones. This report seeks to contextualize what happened to these children, and to understand not only the conditions within the Fort Lewis and Grand Junction schools but also the social, political, and other conditions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This is not done to excuse any deaths or other impacts on Native people subjected to these institutions. No child should ever die at school.”

Not everything was written down, the report pointed out. Superintendents, who were both good bureaucrats and “shrewd political players,” sent messages to Washington, D.C. complaining about lack of resources. Records covered personnel issues, equipment and supply requests, but never children’s names.

“The stories of children crying as their hair is cut come from the children as adults, not from the records of those doing the cutting. The records talk about lice and hygiene. We never hear what happens to the items that are confiscated from the children. It is too easy to imagine that beaded moccasins or a special shirt are simply thrown away, because those things weren’t perceived as having value but, rather, were evidence of a ‘dying race,'” the report said.

Daily life at the off-reservation boarding schools followed military-style institutions, the report indicated, with few firsthand accounts – this regimen was probably coerced, researchers found.

Students were supposed to spend half a day on academics, primarily the three “R’s” – reading, writing and math – but reports from the two schools indicated this didn’t happen for lack of teachers and other resources.

The schools, instead, depended on the students for facilities maintenance, construction of new buildings, irrigation, fences, and other infrastructure; laundry and sewing; and, cooking and cleaning, among other activities. These vocational skills were the primary focus of the curriculum, the report said.

How the students got to the schools also raised red flags. In the schools’ early years, some students were kidnapped, the report said. Parents or others with legal rights were supposed to give their consent, but that didn’t always happen, and there were no consequences for superintendents – who were competing with each other for students and the federal dollars that came as a result – or for Native American agents.

Congress finally intervened in 1893, requiring written permission as a way of demonstrating acceptance of the schools by American Indian parents, “even if just in perception.”

Once a child went to a boarding school, it was difficult for parents to get them back, the report said, adding superintendents and Washington, D.C. officials were reluctant to allow students to return home and often refused to pay for the cost of doing so. One superintendent reported a student who wanted to go home to see his sick mother but refused to pay for it, claiming it would be a waste of money if the mother lived.

Among the most horrific events was cutting hair. Newly-arrived students would have been forced to have their hair cut, with reports of teachers holding some students down. While the government claimed it was for hygiene purposes, the cutting heightened the psychological trauma for those students, the report said.

Living conditions were poor, the report indicated. That included neglect, unsanitary conditions, and poor nutrition, which resulted in sicknesses that often swept across the schools, the report said. The Teller Institute had more problems with epidemics than at Fort Lewis, the report noted. Those illnesses included pneumonia, tuberculosis and in 1907, measles, scarlet fever and smallpox.

Students also faced psychological and physical abuse, including rape. In 1903, Polly Pry, a renowned Denver Post reporter of those days, broke an investigation about sexual abuse of girls and young women by a Fort Lewis superintendent, Thomas Breen, who was never prosecuted for those crimes.

“It is impossible to quantify the abuses that occurred at schools” where students and staff had no recourse, the report said.

Students also lost their Native identities, according to the report. They were stripped of their Native names for English names, a dictate from the federal government. Students rolls were almost entirely anglicized or given Hispanic names, the report said. Sometimes, the schools gave students the names of famous people or even teachers at the school. Superintendents, particularly at the Teller Institute, weren’t careful about identifying the tribal affiliations of students – the report said about one superintendent that it reflected his “absolute ignorance” about tribal affiliations.

Some students weren’t even American Indian. In order to bolster enrollment and the federal dollars that came with it, sometimes superintendents resorted to enrolling students with Mexican or South American heritage.

The lack of accurate identity meant the graves of the students who died at the schools didn’t include the students’ tribal names. Most graves, however, are no longer marked.

“It is reasonable to assume that Fort Lewis cemetery also had wooden markers at some point that have been lost to time,” the report said.

Finally, the report noted earlier work done by Fort Lewis College, including an acknowledgement by the college on the history of the Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School. The college “has been working towards understanding the implications of that history and creating programs of reconciliation for both the college and the wider Durango community,” the report said, adding those efforts that go back to 2017.

Today, Fort Lewis College is designated by the federal government as a Native American-Serving Non-Tribal Institution, with more than 10% of its student body Native American. The college enrolls around 1,400 Native American students each semester from up to 185 tribal nations. Eligible Native American students can attend the college tuition free.

In addition, the Colorado Department of Human Services also worked on an investigation of the Grand Junction boarding school, which now operates as the Grand Junction Regional Center. By the time HB 1327 passed, there had already been a multi-nation consultation about the Teller Institute, along with other conversations about appropriate methods of investigation, tribal ceremonies, and other matters relevant to the Fort Lewis and Teller Institute schools.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com