Douglas County judge wrongly let man represent self at trial, appeals court finds

A Douglas County judge failed to ensure a defendant understood the charges against him and the consequences of proceeding without a lawyer before she allowed him to represent himself at trial, Colorado’s second-highest court ruled on Thursday.

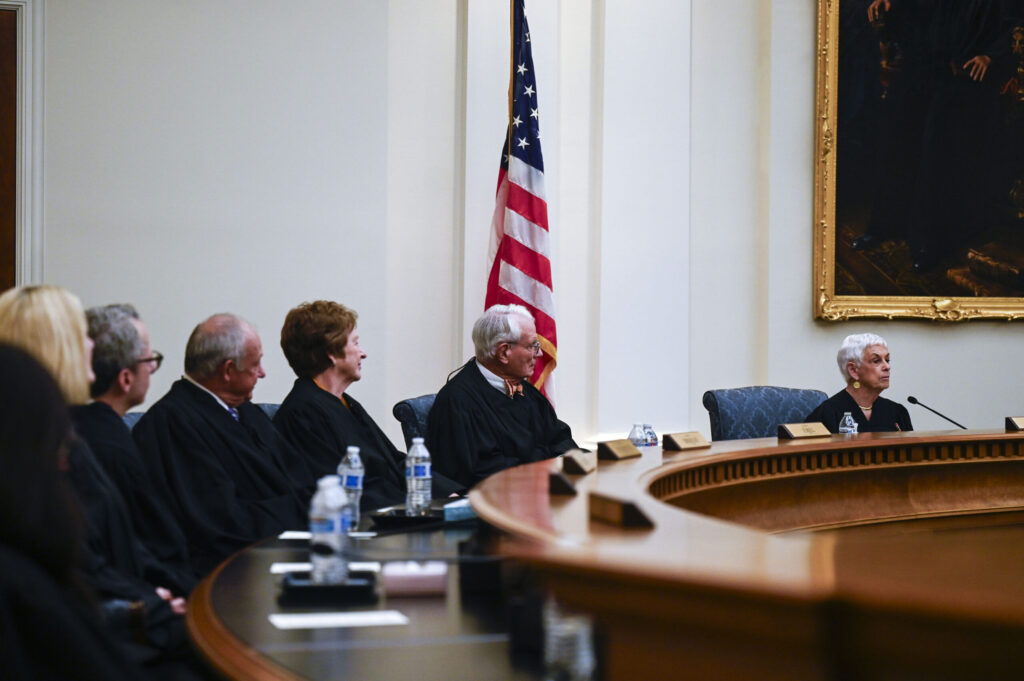

Criminal defendants may give up their constitutional right to counsel, but the decision must be voluntary, intelligent and knowing. A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals acknowledged that John Robert Tesar may have volunteered to proceed alone, but he lacked a clear understanding of what was going on – including that he was entitled to a lawyer in the first place.

“Tesar’s actions and comments,” wrote Judge Jerry N. Jones in the Aug. 24 opinion, “indicate that he didn’t understand that he had an unconditional right to be represented by counsel or that the court would appoint counsel for him if he were indigent.”

Case: People v. Tesar

Decided: August 24, 2023

Jurisdiction: Douglas County

Ruling: 3-0

Judges: Jerry N. Jones (author)

Stephanie Dunn

Katharine E. Lum

Background: Appeals court finds Arapahoe judge mistakenly allowed man to represent self at trial

To determine if a defendant is validly giving up his right to an attorney, judges in Colorado provide an “Arguello advisement,” named after a 1989 state Supreme Court case. Although judges do not have to recite the list verbatim, there are more than a dozen questions they should ask, covering the defendant’s understanding of legal procedure, knowledge of his rights, and the specific charges and penalties he faces.

Tesar stood accused of stalking, harassment and violating a protection order, also known as a restraining order. In August 2020, his lawyer withdrew and Tesar applied for a public defender. However, the public defender’s office determined his financial status rendered him ineligible for representation.

At a conference with District Court Judge Patricia Herron, Tesar indicated that if the public defender could not represent him, he would proceed without a lawyer. The prosecutor asked Herron to give Tesar an Arguello advisement.

Herron said she would mail Tesar an advisement for him to sign, which “tells you, essentially, it is very hard to represent yourself and that it’s not advisable.” There was no indication Tesar ever received or signed a document.

Herron also did not review Tesar’s understanding of the case with him personally, despite many signs Tesar was confused about the process. For example, Tesar said, incorrectly, that his harassment charge was a felony, and did not comprehend the elements the prosecution had to prove. Tesar also arrived at trial without having received key evidence, to which Herron responded it was “your job” to obtain it.

At various points, Herron did stress to Tesar it was far preferable to have an attorney. She was also surprised that Tesar did not qualify for a public defender, as he was unemployed at the time. Tesar responded he understood the judge’s warnings and his “faith is in the jurors.”

At the same time, Tesar communicated to Herron that he was unable to obtain a private or public defense lawyer, not that he was refusing representation altogether.

A jury found Tesar guilty on most of the charges and he received 18 months in jail. The public defender’s office provided Tesar an attorney for sentencing only.

On appeal, Tesar argued that trial judges have the responsibility to review the public defender’s denial of representation and appoint counsel themselves if they find it warranted. Herron reportedly made no attempt to do so, nor did she ensure Tesar received the information contained in the Arguello advisement, including his right to compel witnesses to testify.

“Mr. Tesar consistently indicated that he did not want counsel to represent him in this case,” countered Assistant Attorney General Jaclyn M. Calicchio, arguing for the Court of Appeals to uphold his convictions.

The appellate panel agreed with Tesar. Herron had clearly explained to Tesar that it would be far better to have an attorney, Jones wrote, but she did not address Tesar’s impression that he had to proceed by himself because the public defender’s office had turned him down.

Also, “the facts in the record don’t ‘clearly show’ that Tesar understood the charges against him, the elements of those charges, or the range of possible penalties,” Jones added.

The panel ordered a new trial.

The case is People v. Tesar.