Appeals court judge suggests Supreme Court revisit ruling about defendants’ seized property

One judge on the state’s second-highest court has suggested the Colorado Supreme Court clarify its own recent decision governing how convicted defendants may recover personal items seized by police, calling the ruling logically inconsistent.

In December, the Supreme Court decided Woo v. El Paso County Sheriff’s Office, involving a convicted defendant who claimed law enforcement had failed to return more than $18,000 of property seized during the investigation. The justices explained that the proper protocol involves filing a motion for return of property through the underlying criminal case in any of three windows: before the deadline to appeal, after the appeal is decided or when postconviction proceedings are occurring.

The key factor for those three intervals is that a trial court still has jurisdiction over the case. But what if the defendant does not appeal or does not pursue postconviction relief, but he still wants his belongings back? In that scenario, he may be out of luck.

“Woo appears to create an inconsistency for which I see no basis in law,” wrote Judge Jerry N. Jones in a June 15 concurring opinion. “According to Woo, if a defendant doesn’t file a direct appeal and doesn’t file a motion for return of property within the time for filing a direct appeal, the district court loses subject matter jurisdiction over the case and therefore can’t rule on a later-filed motion for return of property.”

Case: People v. Valdez

Decided: June 15, 2023

Jurisdiction: Boulder County

Ruling: 3-0

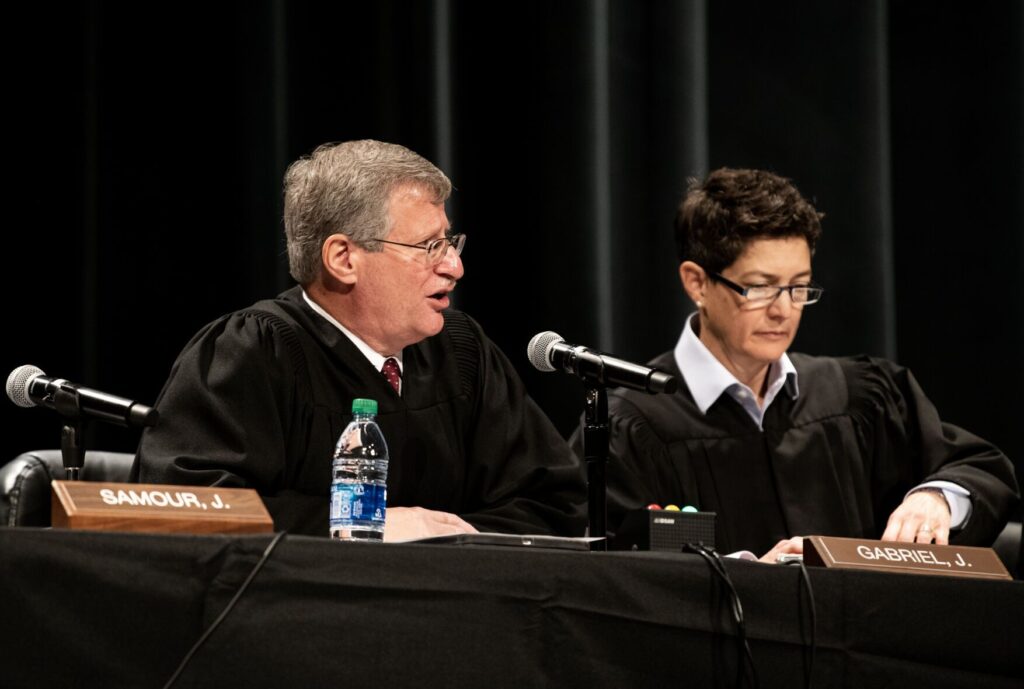

Judges: Stephanie Dunn (author)

Katharine E. Lum

Jerry N. Jones (concurrence)

Background: State Supreme Court clarifies how defendants may ask government to return their property

In the case at hand, Tanner Anthony Valdez pleaded guilty in Boulder County in order to resolve multiple criminal cases against him. A judge sentenced him to five years of prison in 2019. Valdez did not appeal.

Two years later, Valdez filed a motion asking for a court to order the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office to return 38 items allegedly seized as part of a search warrant. The possessions included electronics, clothing and cash.

“The seized property is not contraband and was not used in the commission of the offenses to which Mr. Valdez was charged,” he wrote. “There are no longer any grounds for the continued retention of the seized property.”

District Court Judge Thomas F. Mulvahill denied Valdez’s request. He was not “in a position to determine who the lawful owner is, whether any items still have evidentiary value, and whether any items are contraband,” Mulvahill wrote. The judge suggested instead that Valdez contact the sheriff’s office.

Valdez, representing himself, then appealed, asking for Mulvahill to order the return of his property or else hold a hearing to determine who the rightful owner is. The Colorado Attorney General’s Office opposed the request, arguing Valdez had filed his motion long after the trial court’s jurisdiction over the case had ended.

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals, relying on the Woo decision, agreed Mulvahill’s jurisdiction had ended in July 2019, when the deadline for Valdez to file an appeal had expired. While it was possible for trial judges to “reacquire” jurisdiction when a defendant asks for postconviction relief, a request to recover seized property is not grounds for relief by itself, wrote Judge Stephanie Dunn in the majority opinion.

She added, as an aside, that the panel’s decision came “as best we understand Woo.“

Jones wrote separately with a more direct warning about the inadequacy of the Supreme Court’s guidance. Why, he wondered, would trial judges regain jurisdiction over a criminal case following an unsuccessful appeal, but lose jurisdiction if there is never an appeal in the first place?

“In both cases, there is nothing for the district court to do and the defendant is in exactly the same place,” he wrote. Yet, for purposes of seized property, a defendant can try to recover his possessions in only one of those scenarios.

Jones elaborated that the process endorsed by the Supreme Court means defendants whose personal items are still in police custody might file an appeal, however frivolous, just to ensure they can one day ask for their property back.

“This inconsistency creates odd incentives,” Jones wrote. “Perhaps the supreme court will clarify this matter in a future opinion.”

Antony Noble, a defense attorney, agreed the Woo decision did not acknowledge that seized property generally loses any value as evidence only after the time expires for a defendant to challenge his conviction – and the trial court has lost jurisdiction. He suggested changing the procedural rules to allow the return of seized property to be its own basis for postconviction relief.

“If that is the only claim, the seized property would no longer have an evidentiary use because,” he said, “the defendant would have no further means of challenging his conviction.”

A spokesperson for the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office said it has not returned Valdez’s possessions because, to date, “we have not received proof of ownership of the property from Mr. Valdez.”

According to a 2017 legislative report, law enforcement in Colorado held onto seized property worth at least $2.9 million.

The case is People v. Valdez.