Four Firsts: Biden’s first four judicial appointees in Colorado have begun to make their mark

One month before President-elect Joe Biden would take office, his incoming White House counsel, Dana Remus, sent a letter to Democratic senators outlining the new administration’s expectations for who the president would consider for high-level appointments in the justice system.

“With respect to each of these positions,” she wrote, “President-elect Biden is eager to nominate individuals who reflect the best of America, and who look like America.”

Over the next two years, with the guidance of Colorado’s two senators, Biden would place three new judges on the seven-member federal trial court based in Denver and one judge on the appeals court that covers Colorado and five neighboring states. Some of them fell into the specific categories requested in Remus’ letter – public defenders, civil rights attorneys.

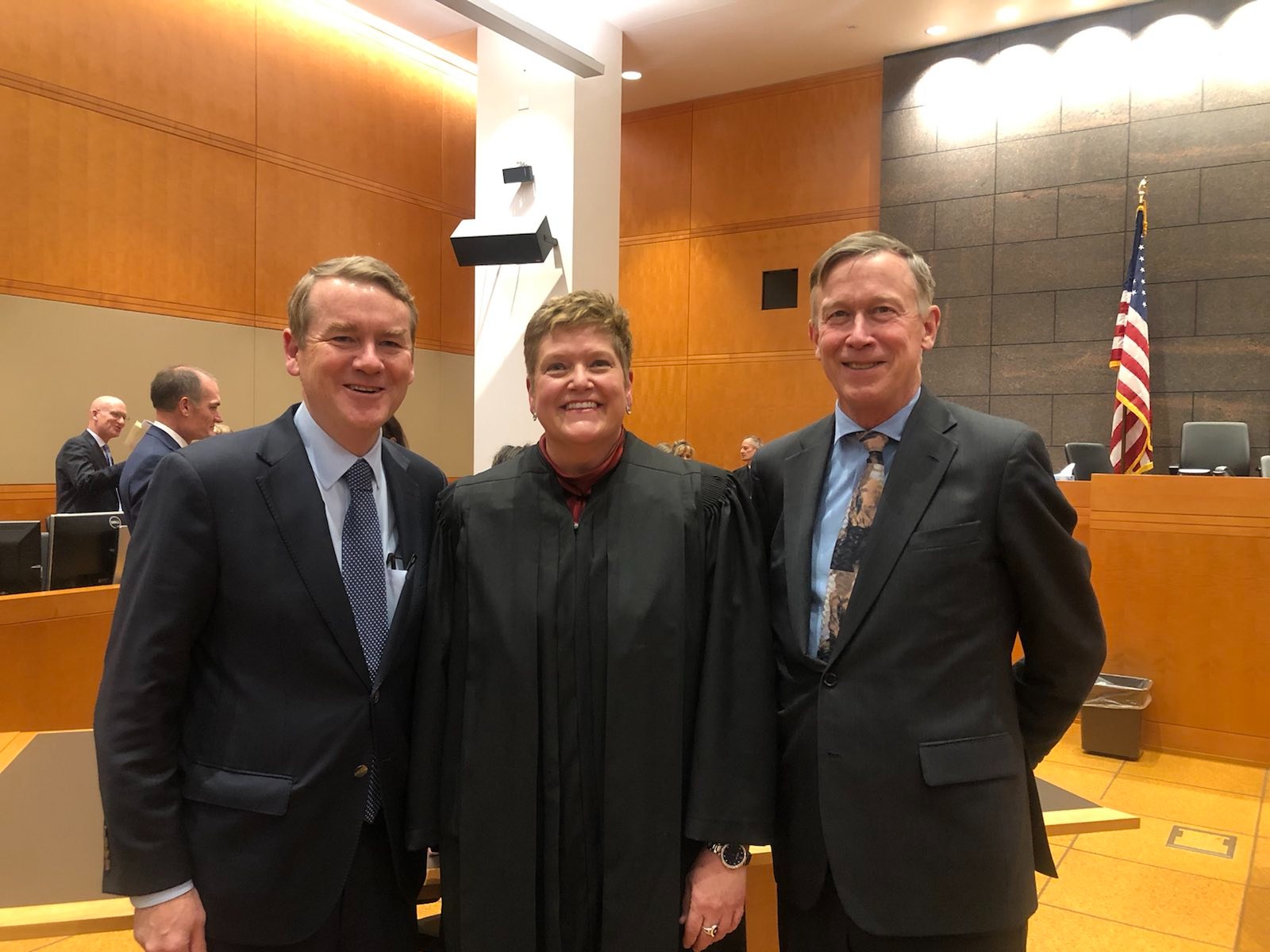

“The joke is that a federal judge is somebody who knows a United States senator,” Frances Koncilja, who was involved in screening applicants for U.S. Sens. Michael Bennet and John Hickenlooper, said at a legal event last year. “We put together candidates, I think, who reflect the community.”

The judges appointed in Colorado between 2021 and 2022 were all “firsts” in various ways. On the U.S. District Court, Judge Regina M. Rodriguez was the first Asian-American appointee. Judge Charlotte N. Sweeney was the first openly gay member. And Judge Nina Y. Wang was the first magistrate judge to receive a lifetime appointment.

In addition, Judge Veronica S. Rossman became the only public defender to sit on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, which is headquartered in Denver.

Collectively, they represented another “first”: No president had ever appointed as many women in Colorado. Biden’s predecessors, Donald Trump and Barack Obama, appointed one and zero female judges, respectively.

Given the influx of new appointees, including a fourth trial judge confirmed this March, University of Richmond law professor Carl Tobias noted in a recent law review article that Colorado “has apparently realized considerably greater success than in most of the nation” in filling judicial vacancies.

On the bench, the Biden appointees have begun to affect the administration of justice in small, but noteworthy ways.

In December, the three trial judges joined with Senior Judge Christine M. Arguello to issue uniform standards for handling civil cases across all four of their courtrooms.

“Overall, having this uniformity makes practice before the judges much more transparent and less onerous,” said Ariel DeFazio, a workers’ rights attorney who formerly worked alongside Sweeney in private practice.

In one set of guidelines, for example, the judges set an expectation “that the appropriate pronouns of counsel, litigants and witnesses be used, which reflects the judges’ concern about the dignity of others regardless of their role in the courtroom,” DeFazio elaborated.

Rodriguez, Sweeney, Wang and Rossman did not respond to interview requests or else declined to comment.

Colorado Politics looked at the judges’ tenures to date, which have ranged from nine months to just under two years, as well as their significant decisions, their public comments, and the observations of attorneys who are familiar with them.

Veronica Rossman

By one estimate, only 7% of federal judges had spent time as public defenders as of 2020. Since Biden took office, multiple appeals courts now have a former public defender sitting on the bench, from the Supreme Court to the 10th Circuit.

“It’s a validation that excellence is rewarded whatever field you are practicing in – corporate law, nonprofit, prosecution and public defense,” said Jon M. Sands, the lead public defender for Arizona who attended Rossman’s ceremonial swearing-in earlier this month. Sands’ appeals court, the neighboring Ninth Circuit, has never had a judge with public defender experience.

Rossman and her family fled the Soviet Union in the face of religious and political oppression, and she spent much of her legal career defending indigent people facing criminal charges.

“You would have never guessed she was a complete stranger to this world. That she had never really spoken a word in a trial court and that she had never represented clients who wore jail jumpsuits,” Virginia L. Grady, the top federal defender for Colorado and Wyoming, said of Rossman’s first days in the public defender’s office. “She showed us how to mine the law and she helped us choose the right words, better words, to write our motions and to speak our arguments to the court.”

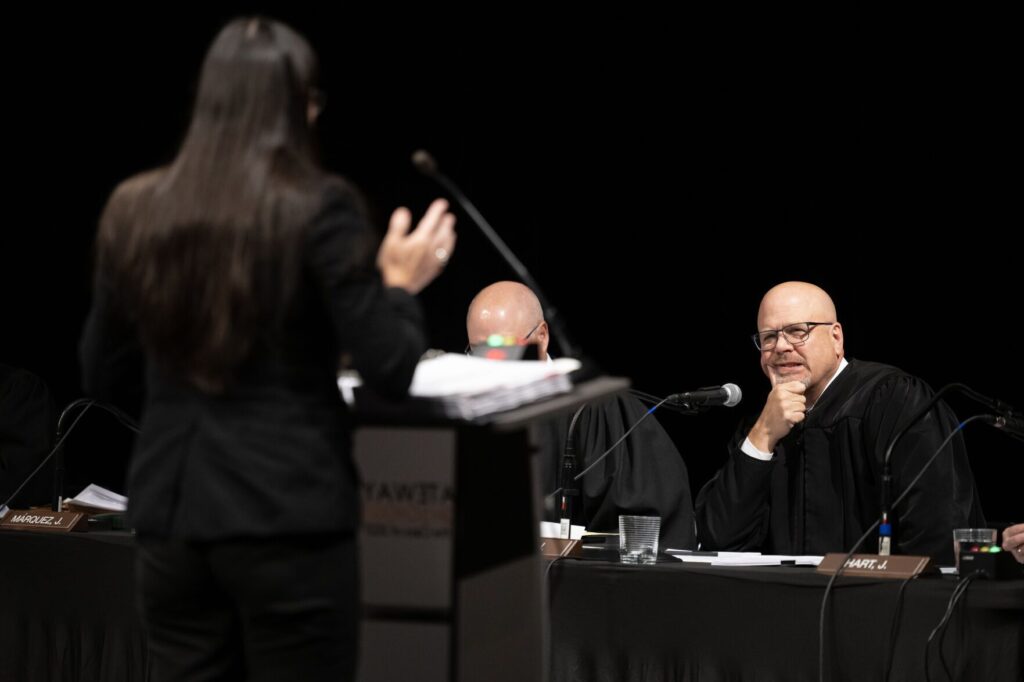

As Biden’s only appointee to date on the 10th Circuit, Rossman has already put her name on several precedent-setting decisions, as well as voiced frustration in dissent.

She authored an opinion holding that a Mesa County sheriff’s deputy can be held liable for not getting help during the 10 minutes he noticed a detainee was not breathing. In another instance, she reinstated a woman’s racial discrimination lawsuit after two trial judges misunderstood the plaintiff’s claims. She also refused to throw out a lawsuit against a handful of Denver police interrogators who coerced a murder confession out of a 14-year-old boy.

In one dissent, Rossman defended how a federal trial judge ordered Denver to modify its policies on homeless encampment “sweeps,” while two other appellate judges overturned the lower court’s injunction. But she also had no qualms about castigating another trial judge for improperly sentencing a criminal defendant in a gang shooting case.

“I don’t have the confidence that this district court understood what Colorado law requires,” she said.

Regina Rodriguez

Rodriguez was among Biden’s first batch of nominees but also happened to be among Obama’s last. Bennet and then-Republican U.S. Sen. Cory Gardner both recommended Rodriguez for a vacancy in 2016. The White House nominated her, but the Republican-controlled Senate never took action.

When Biden re-selected her, progressive groups were not entirely sold on the pick. A former leader within the U.S. attorney’s office and a longtime corporate lawyer, her professional background fit the mold of past nominees, instead of those areas of professional expertise called out in Remus’ letter. Rodriguez also raised eyebrows after two of her prior employers – high-powered, international law firms – paid for a post-swearing-in reception at the Denver Botanic Gardens.

Since then, Rodriguez, due to the rapid turnover on the court, will become the third-most senior active judge next month, after yet another retirement. The 10th Circuit has already issued decisions on cases she handled, including one in which Rodriguez did not agree that a local sidewalk ordinance infringed on a man’s constitutional rights (the appeals court upheld that decision). She even received a speaking slot on the topic of complex litigation at last fall’s conference featuring judges and lawyers from across the 10th Circuit.

“When I came on the bench I thought, ‘Oh, great, we’ll have oral arguments. It will be a great opportunity,'” she said to attendees. “What I found was most oral argument was unhelpful.”

Among Rodriguez’s work to date, she has rejected an effort by an apparent “sovereign citizen” to sue the government officials prosecuting her, allowed a Golden man to sue officers for his injuries due to an early-morning SWAT raid, and directed college officials to impose a lesser sanction on a student who brought a loaded gun into a locker room.

Rodriguez also granted qualified immunity to officers who shot an estimated five dozen bullets at a fleeing car, killing one occupant and paralyzing another.

At her swearing-in ceremony, Rodriguez disclosed she knew she had made the right decision to leave her “cushy” job in private practice after she presided over her first jury trial and saw how seriously jurors took the process.

“When Sen. Bennet called me and said, ‘Are you still up for this?’ I did have to take a moment, I will admit,” she recalled. “Ultimately I had to say yes because this is the service I dreamed about for all of my life.”

Charlotte Sweeney

Unlike her counterparts, Sweeney has made clear the impact she hopes to have during her time on the bench.

During her swearing-in ceremony last year, she paid tribute to the fact that three women are serving on Colorado’s U.S. District Court for the first time, and that their predecessors put their foot in the door to hold it open for their successors.

“The door is now open. And for those who know me, I have shoes for days. I have boots,” Sweeney said. “So, the door is not gonna close on my watch.”

Sweeney was a workers’ rights attorney prior to her appointment who fit squarely within the Biden administration’s aspiration for underrepresented backgrounds. Soon after joining the court, Sweeney became the first district judge to start inserting plain English summaries into her orders for the benefit of self-represented, or “pro se,” litigants. She adopted the practice from U.S. Magistrate Judge Maritza Dominguez Braswell, who is also a relatively new addition to the court.

“We had been talking in my chambers about how to make some of these rulings easier to understand,” Sweeney told The National Law Journal. “It’s hard for the attorneys to follow this, much less a pro se individual.”

While Sweeney has sided against some plaintiffs who alleged civil rights violations, she has also allowed many lawsuits to proceed, including an excessive force claim against a Denver sheriff’s deputy, a suit claiming a prison employee caused an inmate to miss his appeal deadline, and allegations that a company is using deceptive practices in evicting tenants. Two of Sweeny’s decisions – upholding a federal firearms law as constitutional and applying Colorado’s press freedom law in federal court – broke new ground that other judges latched onto in their own orders.

She has also handled several politically salient and controversial topics.

Sweeney rebuffed an attempt by one of Donald Trump’s lawyers to avoid turning over phone records to the congressional committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol. She found she had no jurisdiction to hear a federal employee’s challenge to a COVID-19 vaccination mandate and agreed a group that believes the 2020 presidential election was fraudulent can be held liable for allegedly intimidating voters.

Coincidentally, one early case assigned to Sweeney involved a Christian counselor who challenged the constitutionality of Colorado’s law banning “conversion therapy” – a course of treatment that seeks to change the sexual orientation or gender identity of LGBTQ children, which the American Medical Association says is “not based on medical and scientific evidence.”

Sweeney, the first openly lesbian federal judge in Colorado, penned a forceful conclusion to her order refusing to block the law.

“In the case of children who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, cisgender, transgender, or gender nonconforming, they are entitled to treatment – regardless of its outcome – that does not take a cavalier approach to their ‘dignity and worth,'” she wrote. “And at the bare minimum, they are also entitled to a state’s protection from therapeutic modalities that have been shown to cause longstanding psychological and physical damage.”

Nina Wang

Although she was the most recent of the four appointees, Wang was the only one who came to the bench with experience as a federal judge. Since 2015, she was a magistrate judge, a job that assists with the court’s workload and also performs many of the same tasks of a life-tenured district judge.

While Colorado’s magistrate judges previously came under consideration for presidential appointments, Wang was the first to be successfully confirmed.

“We’ve really looked at the magistrates and said, ‘Why aren’t we pulling from our magistrates?'” said Michelle Lucero, the co-chair of Colorado’s senators’ judicial advisory committee, last year.

“I don’t like to say ‘elevated,’ honestly,” Wang reflected after taking office. “I don’t think of it as an elevation but just a different position.”

A former assistant U.S. attorney – where Rodriguez was her boss and mentor – Wang became an intellectual property attorney and then a magistrate judge in 2015. As a magistrate judge, she generally addressed procedural and administrative matters in cases assigned to district judges, but also handled some cases entirely on her own, with appeals of her decisions going directly up to the 10th Circuit.

Wang’s orders are typically written in detail, with the judge “respectfully” granting or denying relief. On multiple occasions, she has handled cases as a district judge that are eyebrow-raising in their subject matter.

For example, when a student in a “Semester at Sea” program asked that Wang allow him to remain on the ship in lieu of being kicked off in the Mediterranean Sea for misconduct, Wang declined to intervene. And when two brothers sought to collect on a $2.79 billion judgment against the Cuban government for the extrajudicial killing of their father, Wang allowed the men to forge ahead on their unique claim.

Finally, days before the 2022 election, a Republican candidate for a state House of Representatives seat asked Wang to block any enforcement of voluntary spending limits against him, claiming he never actually agreed to limit his spending. Wang quietly sat through multiple hours of testimony before politely declining to take action.

“The Supreme Court has made clear that ‘orderly elections’ lie in the public interest,” she wrote six days before election day. “Recognizing that interest, the Court respectfully concludes that the public interest would not be served by the entry of Plaintiffs’ requested injunction.”