Property rights v. public access: Colorado Supreme Court wades into messy water controversy

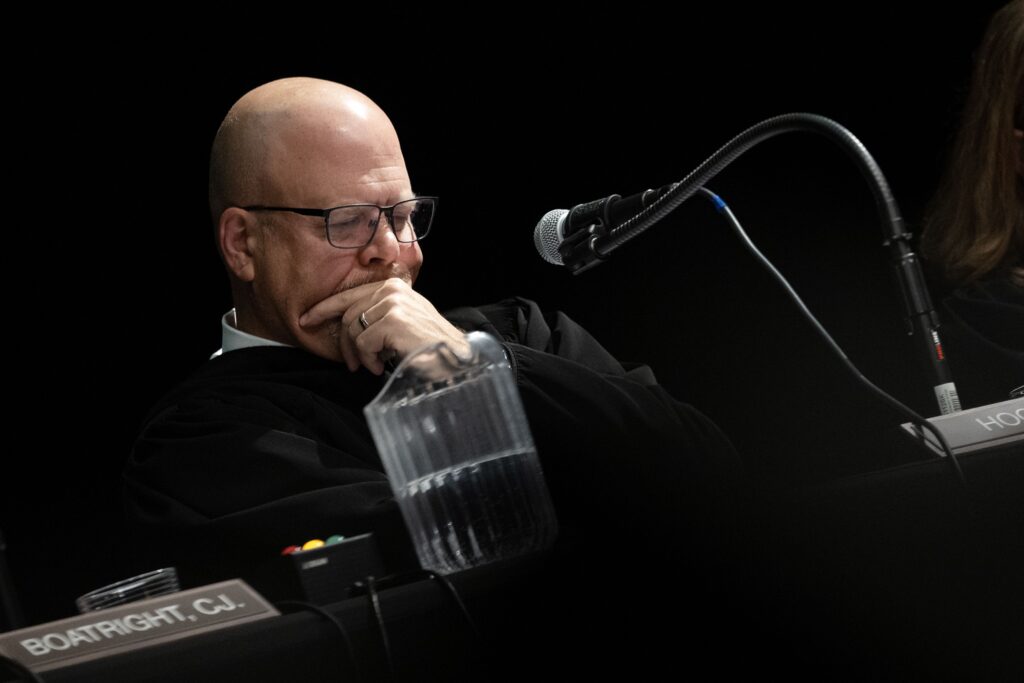

Members of the Colorado Supreme Court heard on Tuesday that they should not upend 150 years of property rights, encourage trespassing and open the floodgates to lawsuits challenging, segment by segment, whether people can wade and fish in waterways that cut across private land.

On the other hand, the justices also heard that Colorado stands alone among western states in failing to ensure the public has recreational access to certain streams and rivers – an obligation dating back to statehood.

Those weighty policy dilemmas stem from a rudimentary legal question: Can 81-year-old Roger Hill ask a court to declare he may stand in his favorite fishing spot in the Arkansas River without getting chased off for trespassing?

“It’s just hard for me to believe, in a state that prizes so much its outstanding outdoor recreational opportunities, that the state of Colorado would say, ‘Sorry, public, you cannot bring this lawsuit and the state is allowed to basically deny that it has any responsibility to protect public access,'” Mark S. Squillace, an attorney for Hill, told the justices during oral arguments.

The facts of the case are relatively straightforward. Hill enjoys standing on the bed of the Arkansas River to fish in a spot owned by Mark Everett Warsewa and Linda Joseph. The property owners have attempted to deter Hill’s trespassing by throwing rocks, firing a gun and threatening to call authorities. Hill filed a lawsuit in Fremont County asking a judge to declare the state actually owns the riverbed and, consequently, Warsewa and Joseph cannot exclude him.

“We don’t want people to have to get arrested or issued a criminal summons and risk an altercation in order to have the legal relations resolved,” said Justice William W. Hood III in explaining the purpose of a declaratory judgment. “We want their status to be resolved in the abstract so we don’t have ugly situations.”

The complication arises through a pair of legal theories that govern property rights for rivers and streams. Under the “equal footing doctrine,” each state, upon its admission to the union, gained ownership of beds underneath rivers and streams that were navigable at the time – meaning 1876, in Colorado’s case. Non-navigable riverbeds were property of the United States and conveyed to private owners through land patents, which is how Warsewa and Joseph came to own the disputed riverbed.

Second, the “public trust doctrine” provides that states hold, “in trust” for the public, the title to navigable waterways, namely to protect commerce. Hill’s lawsuit ultimately seeks to declare his preferred portion of the Arkansas River navigable at statehood, thus making it state-owned and, ultimately, open to public use.

However, there are several roadblocks unique to Colorado.

“What do we do about the fact that our court has said on numerous occasions that we don’t have a public trust doctrine?” asked Justice Melissa Hart.

“What do we do with case law from this court, over a century old, that has said a couple of different times the rivers in Colorado were not navigable at statehood?” added Justice Monica M. Márquez.

Last year, the Court of Appeals cleared the way, in part, for Hill’s lawsuit. A three-judge panel agreed Hill could not technically seek a court ruling on behalf of the state that Colorado owns the riverbed, as Hill had no special interest in the property other than using it like any member of the public.

At the same time, the panel allowed him to pursue a declaratory judgment that he could not be excluded from the spot, as Warsewa and Joseph had taken action specifically against him for using the riverbed.

“If, as Hill alleges, the relevant segment of the river was navigable at statehood, then the Warsewa defendants do not own the riverbed and would have no right to exclude him from it by threats of physical violence or prosecution for trespass,” wrote Judge Ted C. Tow III.

Multiple outside organizations weighed in to the Supreme Court urging a reversal. They pointed out Colorado already works with private property owners to achieve public access in waterways, and it would be dangerous to give people standing to sue only if they trespass on private land and are threatened with violence or prosecution.

“Incentivizing trespass is not sound public policy, will inflame tensions between private property owners and stream-based recreationists, and undermines the existing efforts of … landowners to resolve potential conflicts with river users through negotiated access agreements,” wrote the Colorado Farm Bureau and multiple landowners on the Western Slope.

However, 12 professors of natural resources and property law pointed out that Colorado is the only western state that has not acknowledged whether its waterways are navigable and open to public access. In other states, court cases have affirmed the duty to hold waterways “in trust” for the public, which the other branches of government have then implemented. Although there have been efforts to enact the public trust doctrine in Colorado, they have been unsuccessful.

“We may be an outlier,” observed Hart, “but it may be because of our political branches that we’re an outlier.”

Members of the Supreme Court recognized the many apparent contradictions within Hill’s case. For example, the Court of Appeals ruled Hill could not ask for the state to be declared the riverbed owner, but that would be the only logical explanation if he were permitted to fish there lawfully.

And crucially, Hill must show he has a legally protected interest at stake to even pursue his lawsuit – but whether he has an interest hinges on the public’s right to access the riverbed in the first place.

In the state’s view, the desire to fish unmolested is not specific enough to give Hill standing to sue.

“The interest that he’s seeking to vindicate is one that, under his theory, belongs to the whole public,” said former Solicitor General Eric R. Olson. “There’s nothing special about him.”

The case is State of Colorado v. Hill.