Divided appeals court OK’s corrections department’s violation of speedy trial law

Colorado’s second-highest court last month declined to overturn a man’s Arapahoe County convictions, while acknowledging the head of the Colorado Department of Corrections failed to follow a law designed to give detainees a speedy trial.

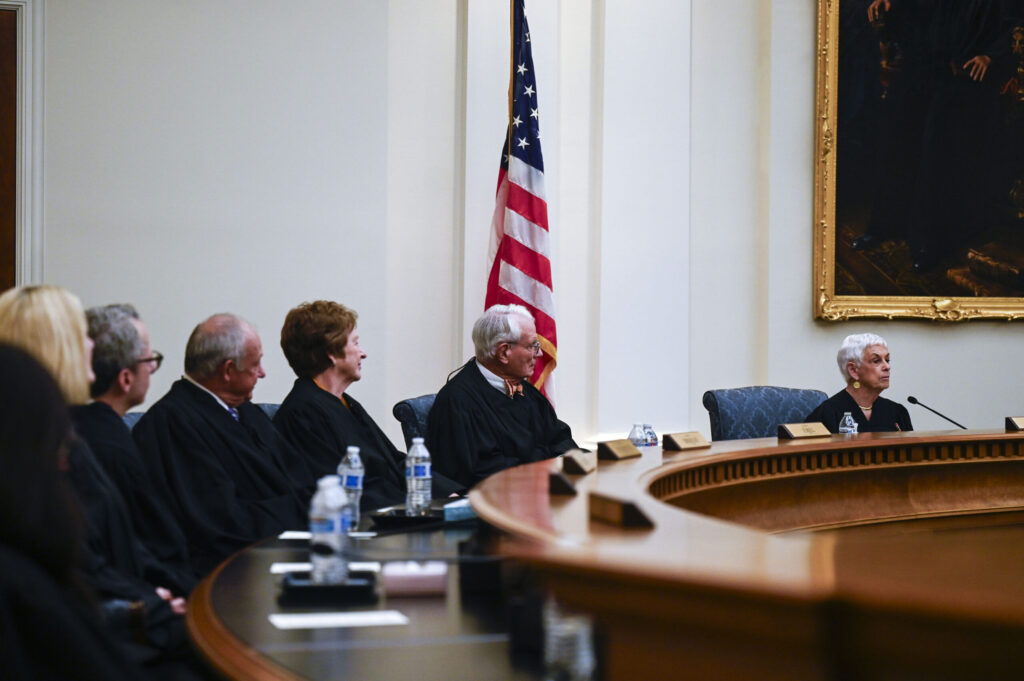

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals noted the department’s then-executive director, Rick Raemisch, did not forward to the prosecutor or the trial judge a communication from Tremaine Dwayne Speer invoking his right to be brought to trial. Speer had been detained in the Aurora jail for 14 months on pending charges, and state law obligated Raemisch to forward the letter “forthwith” so that Speer could be tried within 182 days.

By 2-1, the panel believed Raemisch’s noncompliance had not harmed Speer. Despite the prosecution and trial judge being unaware of Speer’s request, his jury trial did, in fact, occur within 182 days of submitting his letter to Raemisch.

“Speer’s rights related to a speedy disposition weren’t defeated by Raemisch’s violation,” wrote Judge Craig R. Welling, “and his trial wasn’t delayed past the expiration of the speedy trial deadline. Instead, Speer’s speedy disposition rights were vindicated notwithstanding Raemisch’s failure.”

Judge Timothy J. Schutz, however, believed the majority disregarded what the Colorado Supreme Court has said about the law in question – the Uniform Mandatory Disposition of Detainers Act (UMDDA). The law’s purpose is not only to give detainees a speedy trial, nor is that its primary purpose, Schutz wrote.

Instead, the Supreme Court has recognized the main function of the UMDDA is to resolve pending criminal charges against those already serving prison sentences. In doing so, defendants will avoid prolonged stays in jail that disrupt the rehabilitative programming they receive in prison.

Schutz believed it a mistake to overlook a UMDDA violation based solely on the defendant’s trial date.

“Neither the (prosecution) nor the majority opinion points to, nor could I locate, a decision from the Colorado Supreme Court that supports the conclusion that a superintendent’s wholesale failure to comply with the UMDDA may be summarily dismissed if the defendant is brought to trial within the speedy trial time period,” Schutz wrote.

In Speer’s case, he was released from prison to parole in July 2016. Immediately, he committed several armed carjackings and was taken into custody again the next month. From August onward, he remained at the Aurora jail pending the resolution of the vehicle theft charges, but he was technically under the supervision of the corrections department.

Fourteen months later, in December 2017, Speer wrote to Raemisch and referenced his desire for “speedy and final disposition” of his pending case. The next month, he sent a second letter expressly invoking the UMDDA. Under the law, a state prisoner who is detained in a local jail for untried offenses may write to the court and the prosecution to demand a trial within 182 days. The superintendent of the facility is obligated to deliver the letter “forthwith.”

The UMDDA explicitly provides a consequence for failing to bring a defendant to trial within the deadline: dismissal of the charges. However, there is no mention of what happens when a superintendent neglects to deliver the letter in the first place.

In May 2018, Speer’s attorneys moved to dismiss the pending charges due to Raemisch’s UMDDA violation. District Court Judge Andrew Baum denied the motion, reasoning that even though Raemisch never forwarded the letter, Speer’s trial was taking place days later – within the 182-day deadline the letter would have triggered anyway.

Reviewing Speer’s case after his conviction, a majority on the Court of Appeals panel agreed with that logic. The prosecution needed to show Speer was not harmed by Raemisch’s failure to provide notice of the letter. Because the speedy trial goal of the law was accomplished, there was no prejudice, Welling wrote for himself and Judge Jerry N. Jones.

To dismiss the charges outright would “create a remedy for a procedural violation that is beyond what the legislature provided,” Welling explained in the March 23 opinion.

Schutz disagreed with the majority’s decision to only look at whether Speer’s trial was timely. Holding a state prisoner in jail awaiting trial can affect the programs they participate in and their “attitude toward rehabilitation,” he wrote. Schutz cited the Supreme Court’s own directive to consider “more than the general factors underlying the constitutional right to a speedy trial” when looking at a UMDDA violation.

“But the trial court never considered this issue, or any other prejudice visited on Speer,” he wrote. “I am concerned that the majority’s analysis fails to track the course chartered by the Colorado Supreme Court.”

The case is People v. Speer.