Federal judge orders Logan County sheriff to explain why he should not be held in contempt

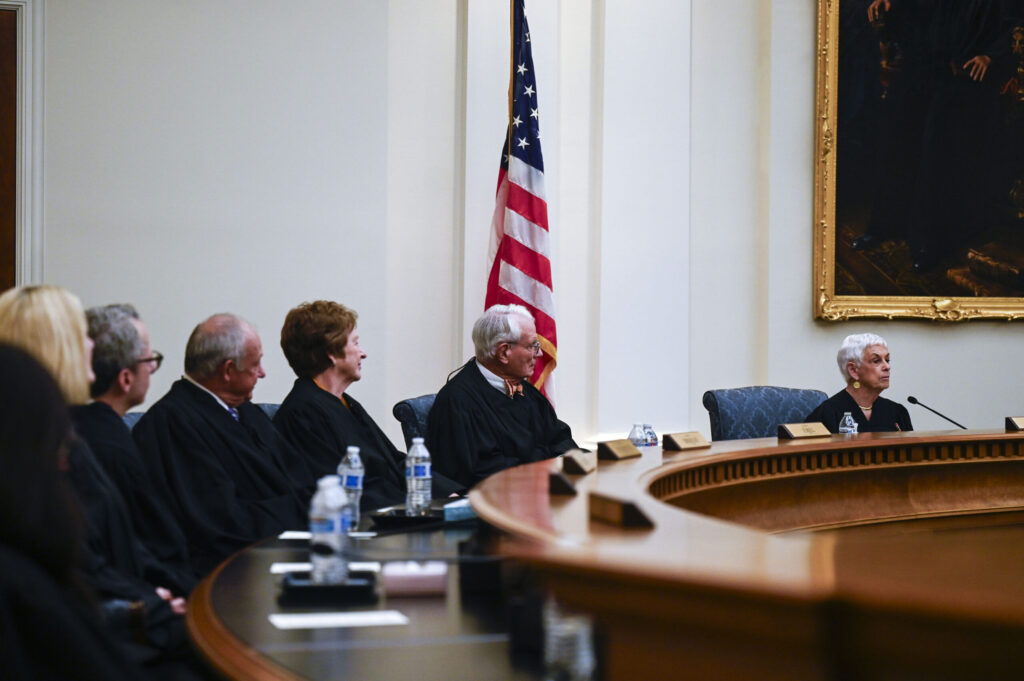

A federal judge on Thursday ordered the Logan County sheriff and two of his subordinates to explain why she should not hold them in contempt for violating a court order to transport a suicidal detainee to the hospital.

U.S. District Court Judge Nina Y. Wang gave the sheriff’s officials until April 18 to provide evidence of what happened to Michael Bretz after he left the Logan County jail last Friday for Denver, more than 12 hours after the jail received an order to take Bretz to the emergency room immediately. At the time, Bretz had a gaping wound on his inner arm that his attorneys feared was life-threatening, prompting them to seek federal intervention.

As of April 6, neither Bretz’s attorneys nor the sheriff’s lawyers knew for certain if Bretz had seen a doctor since his removal one week prior.

“I don’t know whether he’s gone to the hospital, your honor,” said Andrew R. McLetchie, an attorney for Sheriff Brett Powell, Undersheriff Ken Kimsey and Lt. Jared Harty.

“You can’t confirm factually for this court that he has received medical care?” Wang asked.

“No, I cannot,” McLetchie conceded.

Bretz stands accused of multiple child sex offenses in Logan County. Around the time of his arrest in February, he allegedly tried to kill himself by slicing into his arm and throat. Bretz subsequently made other suicide attempts by reopening the injury to his wrist, most recently on March 22 when he bit into his wound while appearing in court.

The Logan County jail reportedly did not have the ability to provide care for the now-open wound. Bretz alleged the injury began “smelling badly and oozing a green substance,” and his state public defender indicated Bretz’s hand “has turned purple.”

On March 29, Bretz, represented by a law firm in Texas, filed a federal lawsuit against the sheriff and his two subordinates. He simultaneously sought a temporary restraining order compelling the defendants to take him to the hospital immediately.

The case was assigned to Wang, but because she was out of the courthouse, U.S. District Court Senior Judge R. Brooke Jackson stepped in to handle the urgent request. Although the defendants wanted time to talk to their attorneys before responding to the motion, Jackson looked at the picture of Bretz’s gaping wound and decided to order immediate medical care.

“Just judging by the photograph it seems apparent that medical attention is necessary,” Jackson wrote on March 30. “An unnecessary trip (if it turns out to have been unnecessary) is a relatively minor inconvenience. The harm that could potentially be caused by an untreated open infection could be quite serious.”

Bretz’s attorneys delivered Jackson’s order to the jail after 5 p.m. that day. However, the jail did not take Bretz to the hospital. Instead, shortly after 9 the following morning, parole officials arrived and took Bretz to the Denver Reception and Diagnostic Center, which is part of the state’s prison system.

Afterward, both sets of attorneys seemed unaware of what happened to Bretz.

“The order was clear it was to be an immediate transfer to a hospital emergency room,” James P. Roberts, Bretz’s lawyer, told Wang on Thursday. “I don’t believe that is compliant with the TRO. They knew the court ordered them to do something and they decided not to do it.”

Roberts has asked Wang to hold the sheriff’s officials in contempt and impose sanctions for disobeying Jackson’s directive. The defendants insisted they “substantially complied in good faith” with the order, claiming they were forced to choose between immediately transporting Bretz to the emergency room or adhering to the existing plan to take him to DRDC, where he could receive medical care.

“I respect the rule of law and court orders and my clients do, too,” said McLetchie. “They just thought they were in a Catch-22 and thought this was the best way to get him care and comply with the order.”

Wang asked McLetchie if he knew whether Bretz received treatment once at DRDC, and McLetchie responded his “working assumption” was that Bretz would have gotten care “as a matter of course.”

“That’s not my question,” the judge responded.

She permitted the defendants to submit evidence showing what treatment Bretz received, when they learned of the plan to transport him to Denver and what actions they took to comply with the temporary restraining order.

The case is Bretz v. Powell et al.