State Supreme Court clarifies effect of serious bodily injury on child welfare cases

Once the government proves that, more likely than not, a child experienced a serious bodily injury, a judge may find no treatment plan is possible to help the parent become fit, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Monday.

The justices took the uncommon step of hearing an appeal directly from Arapahoe County after noting the Supreme Court had never addressed the government’s burden of proof for showing a parent is so unfit that no treatment plan is possible. The court also elected to intervene for fear that the child at the center of the case, L.S., may suffer “irreparable harm.”

However, the Office of Respondent Parents’ Counsel, which represents indigent parents, warned that the decision effectively eliminates second chances when a child happens to sustain a serious injury, even if a parent did not inflict it.

“The ORPC is not aware of any other state with similar law permitting a finding of no appropriate treatment plan in these circumstances. This is unacceptable and unconstitutional, and the legislature must act,” said case strategy director Melanie Jordan.

L.S. was one year old when his mother took him to the hospital. He had a broken leg bone, two other fractures, swelling to his groin and bruising all over his body. Arapahoe County then began child welfare proceedings, formally known as dependency and neglect, which can eventually lead to the termination of a parent’s legal relationship with their child.

Among the steps in a dependency and neglect case, a judge can adopt a treatment plan, which addresses custody and services to be provided for the family. If a case gets to the termination stage, a judge may end the legal relationship if, “by clear and convincing evidence,” a parent is unfit due to a child’s serious bodily injury and no treatment plan would help.

L.S.’s mother asked a judge to find that Arapahoe County had not proven by clear and convincing evidence that L.S. experienced a serious bodily injury. In response, District Court Judge Don J. Toussaint believed that, at the pre-termination phase, “proof of serious bodily injury is not evidence that no treatment plan can be devised.”

Arapahoe County then appealed directly to the Supreme Court.

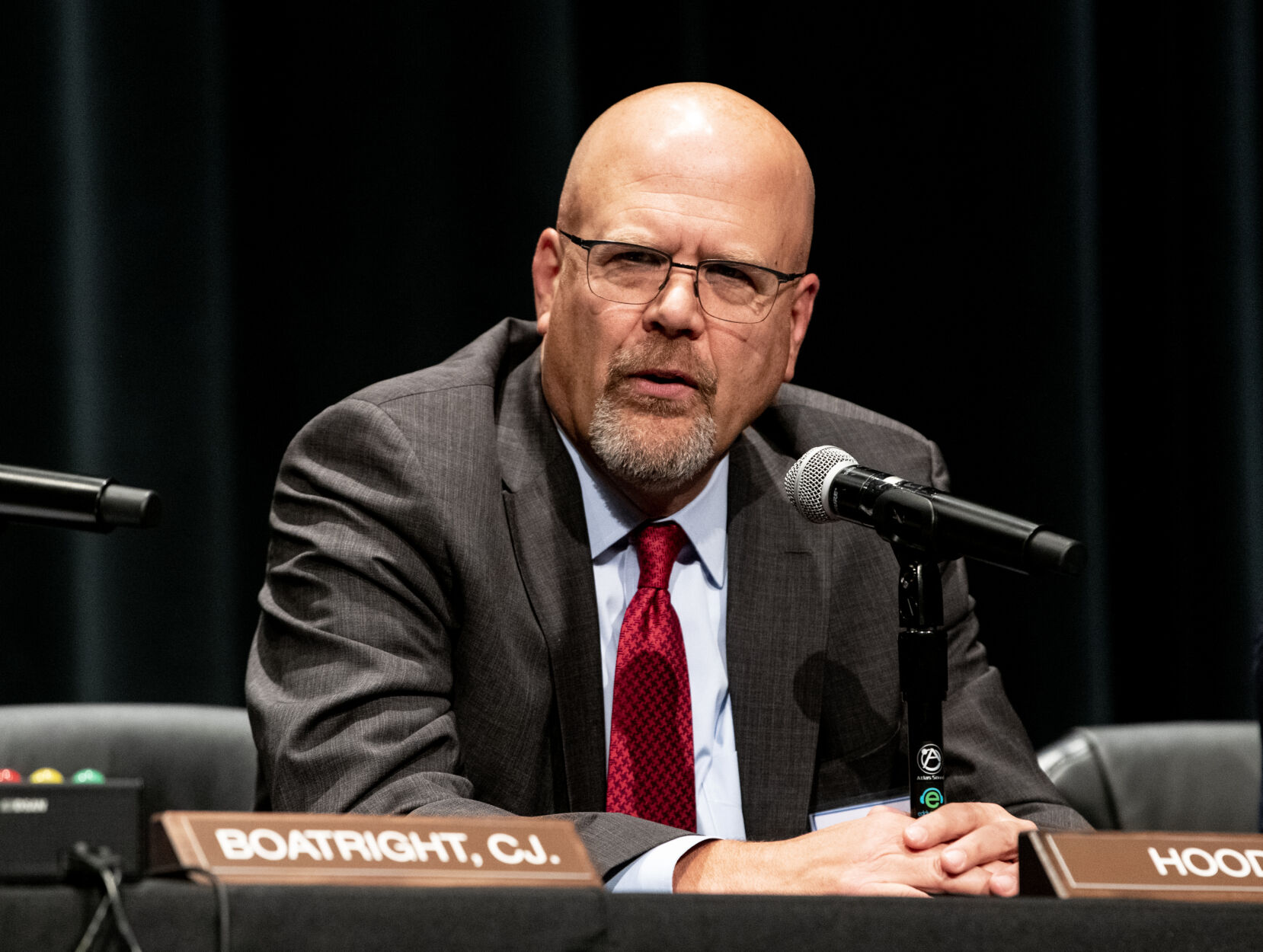

Justice William W. Hood III, in the Jan. 23 opinion, noted the trial court’s goal at the treatment plan phase is to protect the neglected child, while attempting to keep the family together. But it is possible a judge may find no appropriate treatment plan exists. Although the law does require clear and convincing evidence of a single serious bodily injury and no viable treatment plan at the termination stage, Toussaint had misapplied the standard to the current phase of L.S.’s case, Hood concluded.

“(N)either the statute nor our case law supports such a high burden of proof for any stage of proceedings other than termination,” Hood wrote.

As for Toussaint’s conclusion that serious bodily injury is not sufficient grounds to rule out a treatment plan, “the legislature intended to allow trial courts to find that a parent is unfit and no appropriate treatment plan can be devised if the state shows that the child has suffered a ‘single incident resulting in'” serious bodily injury, Hood added.

Ruchi Kapoor, the attorney for L.S.’s mother, portrayed the decision as a major shift to the procedural rights of parents in dependency and neglect cases.

“The Supreme Court’s far-reaching decision has taken off any due process or procedural brakes for parents who find themselves in a nightmare scenario where their children are seriously injured,” she said.

The case is People in the Interest of L.S.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with comments from the parties.