Convictions reversed in 2 cases due to faulty jury instructions

Colorado’s second-highest court reversed the convictions of two Arapahoe County criminal defendants earlier this month, citing the failure by the trial judges to properly instruct jurors about the law on self-defense.

The circumstances of each case differed slightly. In one instance, the trial judge apparently forgot to read the proper self-defense instruction he had previously promised to give. In the second trial, the judge refused to provide any self-defense instruction, even though the jury signaled they wanted to know more about the defendant’s right to defend himself.

The state’s Court of Appeals also identified a further error, involving evidence that was improperly admitted at trial due to an unlawful police stop.

The inadvertent omission

On March 8, 2018, Antwan Deshawn Barmore shot at his romantic partner and her brother at a parking lot near S. Havana St. and E. Florida Ave. in Aurora. Earlier in the day, Barmore and his partner had gotten into an argument, and he had taken her handgun when he left.

The partner arranged for a meetup where Barmore would return the gun, but once in the parking lot, Barmore resisted. Unknown to Barmore, the partner had asked her brother to be present, and he walked up to the car to also confront Barmore.

Barmore eventually walked away, followed by the two siblings. Reportedly, the brother continued to argue with Barmore, and Barmore fired multiple shots with the gun. The bullets hit a vehicle, but no one was hurt. Police subsequently found and arrested Barmore in a nearby neighborhood. A jury convicted him in 2019 of attempted murder, attempted manslaughter and other charges.

At trial, Barmore argued he was acting in self-defense against his alleged assailants. The defense proposed giving the jurors an instruction to consider the total circumstances, “including the number of persons reasonably appearing to be threatening the accused,” when evaluating if Barmore legitimately felt he needed to use force to defend himself.

District Court Judge Ben L. Leutwyler agreed the instruction was warranted under the circumstances and said he would read it to the jury.

But for reasons what were unclear, he never did.

“It appears to be inadvertent,” Jeffrey A. Wermer, Barmore’s public defender, told a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals.

Regardless of the cause, Wermer contended the generic self-defense instruction the jury received did not track with Barmore’s argument that he needed to specifically defend himself against multiple assailants. Therefore, jurors would not have felt obligated to consider all of the circumstances, Wermer argued.

The prosecution attempted to minimize the effect of the missing instruction, faulting Barmore’s attorneys for not catching the mistake at trial and believing Leutwyler’s other instructions alerted the jurors about the need to consider multiple assailants.

The appellate panel sided with Barmore.

“Trial courts have a duty to provide complete and accurate jury instructions on the applicable law,” wrote Judge David Furman in the Nov. 17 opinion. He elaborated that trial judges are required to give the necessary self-defense instructions when some evidence supports the defendant’s theory.

At trial, not only was there some evidence Barmore acted in self-defense, but Barmore’s lawyer told jurors they would receive an instruction that “allows you to consider the number of persons that are appearing to threaten Mr. Barmore.” Coupled with Leutwyler’s admonition to the jury that “you must follow the instructions I give you,” the omitted instruction could have reasonably affected the jury’s verdict.

The panel reversed Barmore’s convictions on that basis. However, the missing instruction was not the only problem the panel detected with Barmore’s case.

After the parking lot shooting, police received a description of the suspect as a 25-year-old Black male wearing a black shirt and carrying a black backpack. Officers later said they responded to “the area,” where they encountered Barmore and ordered him to the ground at gunpoint. Barmore quickly admitted the handgun was in his pocket and that he had acted in self-defense.

Barmore argued in the trial court that Aurora police had committed an unconstitutional seizure under the Fourth Amendment by stopping him without reasonable suspicion of a crime. If true, the unlawful behavior would have required the court to bar evidence from the stop from being used at trial – namely, the handgun in Barmore’s pocket and his statements to police.

After a hearing in which some officers testified, District Court Judge Darren Vahle found police had, indeed, stopped Barmore, but they had reasonable suspicion to do so. He acknowledged the testimony from the prosecution’s witnesses was sparse at times – for example, by failing to establish how far police drove from the shooting site to locate a Black man matching dispatch’s description.

“The particularity of the description, specifically the age and ethnicity, coupled with the clothing of black shirt or coat and a black backpack, (is) actually relatively common,” Vahle said. “There might be young Black males walking around, there might be people with black shirts, there might be people with black backpacks. But if you put all four of those things together, the court finds it to be utterly reasonable to stop this person under those circumstances given the recency of the shooting and the proximity of the neighborhood.”

On appeal, Barmore argued the prosecution, in justifying the police stop, had essentially relied on a race-based description of a suspect to link Barmore to the crime, which did not rise to the level of reasonable suspicion.

“That a shooting occurred in Aurora on March 8, 2018 is not a reasonable basis for believing that a person at an unknown distance and time from that shooting is armed and dangerous simply because he matched a generic description,” Wermer wrote to the panel.

Again, the Court of Appeals agreed with Barmore. The panel ticked through a list of details the district attorney’s office never established at the suppression hearing, including Barmore’s behavior immediately before the stop, how close to the shooting site the officers found him, and whether other people were in the area, too.

“So, the evidence presented was not sufficient to show a reasonable articulable suspicion for detaining Barmore,” Furman concluded.

The case is People v. Barmore.

‘Can you give guidance?’

In March 2018, Joseph Goudy Lugo shot two men outside an apartment complex in Aurora. One victim, Potros Mabany, died and the second was wounded.

Evidence showed Lugo had gone to the apartment building and tried to purchase marijuana from one of the people present. An altercation ensued and Lugo pulled a gun.

At some point, Mabany told Lugo that “my boys … they shoot, too.”

The group then exited to the building’s courtyard where five or six men, reportedly larger than Lugo, surrounded him. One of the men began yelling angrily at Lugo for roughly four minutes. Lugo then pulled his gun, injuring the man who yelled at him and fatally wounding Mabany.

Although Lugo’s primary defense was that the prosecution had not proven he was the shooter, he also requested the jury receive an instruction that Lugo used deadly force in self-defense.

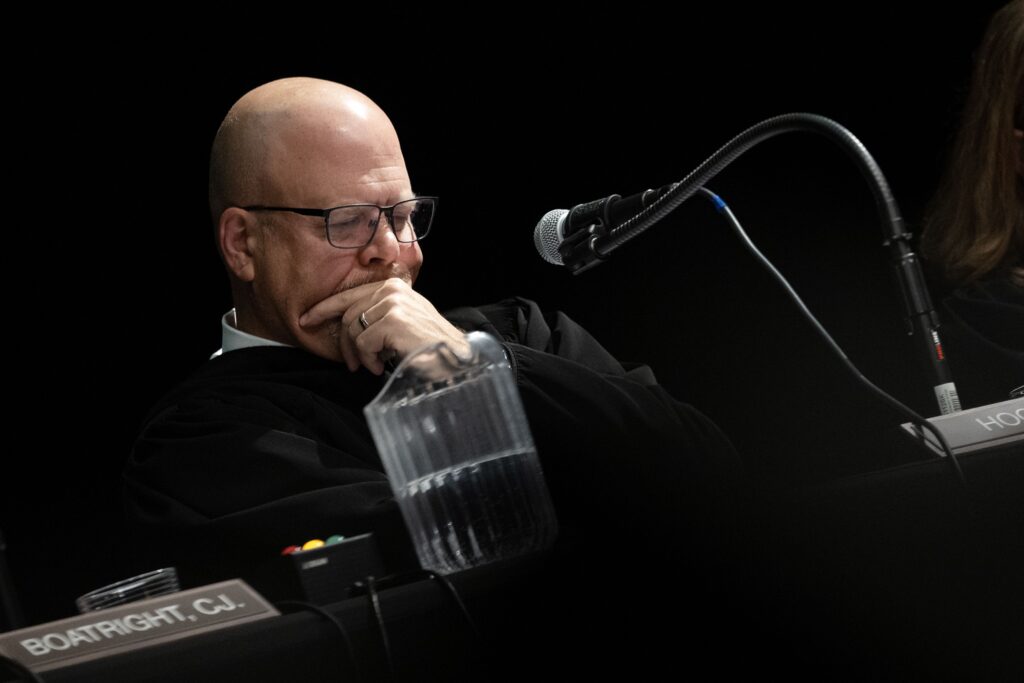

District Court Judge Jeffrey K. Holmes refused to give the self-defense instruction. He noted the inconsistency between Lugo’s argument that he was not the shooter and the notion that he shot in self-defense, but Holmes also believed there was “insufficient evidence” showing Lugo acted in self-defense.

During jury deliberations, however, Holmes received a question from jurors about the topic.

“Some jurors are discussing the possibility if Lugo may have acted in self-defense based on the defenses (sic) alluding to threats against Lugo right before the shooting,” the note read. “We know it is not part of the charges? Can you give guidance?”

Holmes told the jury that they should rely on the instructions he already gave them, and “you have not been given a self-defense instruction.”

The jury found Lugo guilty of second-degree murder.

On appeal, Lugo argued there was some evidence to suggest he feared the group of men surrounding him in the courtyard posed an imminent threat, and was acting in self-defense. If jurors had received the instruction, it would have been the prosecution’s burden to prove he did not shoot in self-defense.

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals believed the lead-up to the shooting contained indications Lugo believed he was in danger. Further, the jurors’ question suggested they, too, felt self-defense was a possibility.

“Because some evidence supported an inference that Lugo believed (1) he faced the imminent use of unlawful force and (2) a lesser degree of force was inadequate to defend himself, the reasonableness of that belief is a question for the jury, not for the court,” wrote Judge David H. Yun in the Nov. 17 opinion.

The panel reversed Lugo’s murder conviction and ordered a new trial.

The case is People v. Lugo.