Appeals court upholds dismissal of Hispanic juror for believing justice system is racist

Colorado’s second-highest court found no problem with the prosecution dismissing a Hispanic man from an Arapahoe County jury because of his observation that the judicial system is unfair to racial minorities.

But for defendant Dustin Aaron Schwarz, the exclusion of the man from his jury exemplified a larger concern that people of color are being turned away from serving because of reasons that, while not explicitly racial, still correlate with race.

“If the jury selection system allows prosecutors to strike people of color who are concerned about (systemic bias) because of their experiences based on race, then juries will never be made up of a fair cross-section of our communities,” argued public defender Casey Mark Klekas on behalf of Schwarz.

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals ultimately found the dismissal of “Juror G” did not violate the U.S. Supreme Court’s prohibition on intentional race-based exclusions of jurors. The prosecutor, explained Judge Anthony J. Navarro, had made clear his problems revolved around Juror G’s statement about the justice system – which was not openly linked to Juror G’s race.

“Under these circumstances, and without an overt prosecutorial reference to the potential juror’s race in relation to his views on the justice system, we conclude that the prosecutor’s articulated reason for the strike was facially race neutral,” Navarro wrote in the Sept. 15 opinion.

The Supreme Court’s 1986 decision in Batson v. Kentucky recognized as unconstitutional the intentional exclusions, or strikes, of jurors based on their race. Although the parties in a case are normally permitted to use “peremptory strikes” to excuse jurors without a reason, defendants sometimes raise “Batson challenges” if a prosecutor attempts to dismiss a juror of color.

The Batson challenge triggers a multistep process, in which the prosecutor must present a nonracial explanation for their peremptory strike and the trial judge then decides whether intentional racial discrimination is likely taking place.

Critics of Batson challenges argue prosecutors may still succeed at dismissing jurors of color by simply advancing a justification that may carry implicit bias, such as the jurors’ demeanor, the fact they have had prior contact with police officers, or their distrust of law enforcement – all of which can have indirect links to a juror’s race.

“Unrepresentative juries occur because communities of color are often unfairly excluded or marginalized because of their race,” testified public defender Joyce Akhahenda to the legislature earlier this year. “It reinforces that this is not ‘our’ system.”

Schwarz, who is white, stood trial in 2019 for a series of robberies he committed in Aurora-area pharmacies. During jury selection, one man with the Spanish surname “Guillen” indicated on his questionnaire he could not be an impartial juror because “the Judicial System is racist.”

The unnamed prosecutor asked Juror G, as the appeals court referred to him, to elaborate.

“I just feel it’s at times unfair, especially with minority race groups,” Juror G said.

The prosecutor then wondered if Juror G could “set that aside” and decide the case based on the evidence.

“It’s a little bit challenging, but I can do it,” responded Juror G.

The man then correctly stated the fundamental principle of criminal cases – innocent until proven guilty – and clarified he believed police officers are “just doing their job” by keeping the public safe. The prosecutor’s final question to Juror G was whether he had any concerns about being a fair and impartial juror.

“Not at all,” Juror G said.

Although the prosecutor did not attempt to excuse Juror G for cause, he used a peremptory strike to dismiss the man. The defense raised a Batson challenge, noting Juror G had a Hispanic name and had explained he could decide the case impartially.

“Judge, frankly, I don’t know if Guillen is a Hispanic surname,” the prosecutor interjected.

Even though Juror G’s oral answers were more even-handed than his questionnaire statement, the prosecutor continued, “I have some concerns with any member of the jury who enters the courtroom if there’s some prejudice or bias by either law enforcement or the system.”

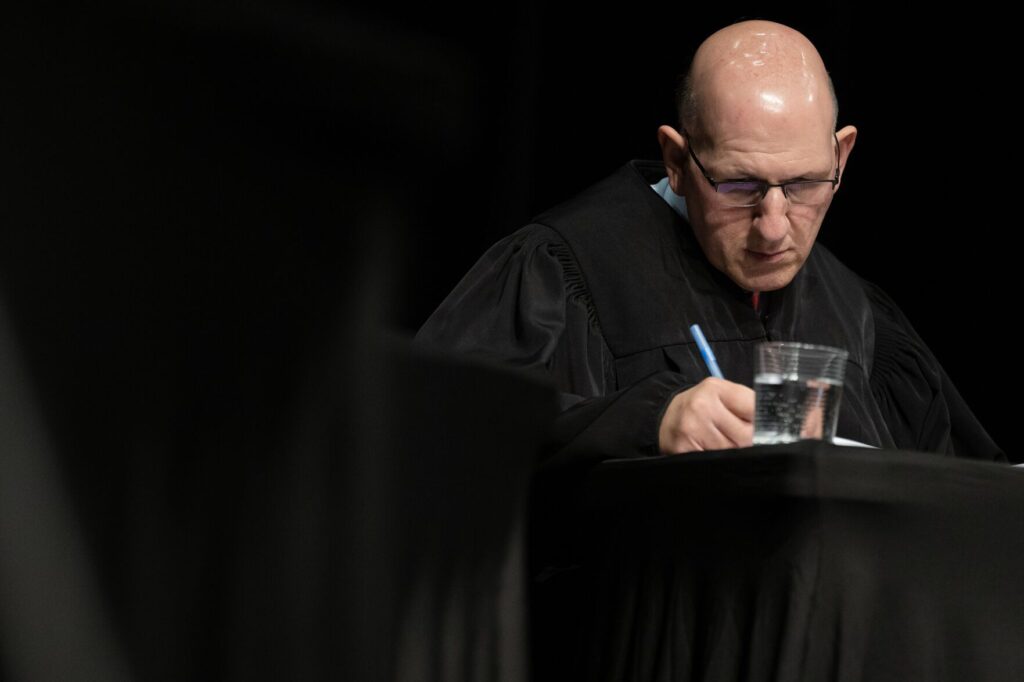

District Court Judge Ryan Stuart did not believe the defense had even plausibly claimed the strike of Juror G was based on race. But, “if an appeals court disagrees with me,” Stuart added, “Mr. Guillen believes that the judicial system is racist.”

That belief, combined with Juror G’s admission that his brother was convicted and “harassed” by police, amounted to nonracial reasons for the strike.

Following his conviction, Schwarz appealed and argued the prosecutor’s explanation for dismissing Juror G was inherently race-based.

“Are jurors expected to lie or stay silent when asked about the criminal justice system’s treatment of minority groups? To be eligible to serve, must a prospective juror conceal any racial discrimination they or their family have experienced?” Klekas wrote to the Court of Appeals.

The government defended the decision to strike Juror G, disputing whether he was even Hispanic and, even if he was, contending Juror G’s views about systemic bias were unrelated to his race. Further, the Colorado Attorney General’s Office suggested Juror G might have intentionally misrepresented his ability to be fair in order to infiltrate the jury.

Juror G’s promise to be impartial could have actually been “an effort to be seated and bring his preconceived view of the judicial system into the jury room,” wrote Olivia Probetts to the court.

The appellate panel based its decision in large part on the case of People v. Ojeda, which the Colorado Supreme Court decided earlier this year. There, as in Schwarz’s trial, a prosecutor struck a Hispanic juror who had concerns about systemic racial bias in the justice system. Unlike Schwarz’s case, however, the prosecutor justified the strike by mentioning “the fact that the defendant is a Latino male.”

The Supreme Court agreed to order a new trial because the prosecutor’s explanation was explicitly linked to race.

In contrast, the Arapahoe County prosecutor in Schwarz’s case had not made the same mistake.

“Indeed, the prosecutor did not refer to Juror G’s race or ethnicity at all,” Navarro wrote. He pointed to the Supreme Court’s Ojeda opinion, which acknowledged a difference between a juror merely expressing concerns about the criminal justice system and a prosecutor then tying those views to race.

Because Schwarz’s prosecutor had not gone that far, the panel upheld his convictions.

Currently, the Colorado Supreme Court’s criminal rules committee is preparing to send a proposal to the justices that seeks to reduce the exclusion of people of color from juries. The committee debated the rule change behind closed doors in July, months after a similar measure failed to advance in the General Assembly due to opposition from district attorneys.

A Judicial Department spokesperson refused to disclose the specifics of the upcoming proposal, but a preliminary draft from this summer laid out specific justifications for excusing jurors that are presumed to be invalid. Peremptory challenges would generally be turned aside if, for instance, a juror lives in a “high-crime neighborhood,” is a non-native English speaker, or has friends or family members who have been arrested.

Notably, the proposal would also invalidate juror strikes for those who express distrust in law enforcement or believe police engage in racial profiling.

The case is People v. Schwarz.