Appeals judge to law enforcement: Be wary of repeated failures to retain evidence

A judge on the state’s Court of Appeals has sent a stern warning to law enforcement following a series of missteps in Boulder County that resulted in a failure to retain or turn over evidence.

Judge Lino S. Lipinsky de Orlov on Thursday authored a concurrence upholding William Robert Eason’s 2021 criminal conviction and finding no violation of his due process rights under existing court precedent. But Lipinsky also believed an agency’s pattern of negligently failing to retain evidence could qualify as a constitutional violation in the future.

“The courts will not tolerate a law enforcement agency’s systemic failure to comply with its document retention policy or any other retention requirement imposed by law,” he wrote on May 19.

Prompting Lipinsky’s admonition was the revelation prior to Eason’s trial that the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office had failed to abide by its three-year retention policy and had instead deleted one body-worn camera video after 30 days. The video contained a deputy’s hourlong interaction with the two victims in Eason’s case, and Eason saw it as key to impeaching their credibility.

On appeal, Eason’s attorney further asserted that in two of his other cases in Boulder County from around the same time, the prosecution had failed to request video recordings in time and the sheriff’s office had destroyed them.

Boulder County District Attorney Michael Dougherty said that at the time of Eason’s arrest in July 2020, the sheriff’s office was continuing its multiyear transition to body-worn cameras. He added the Court of Appeals did not find systemic retention problems exist in the county currently.

“Since that time, the sheriff’s office has worked to refine and improve their retention policy for body camera footage,” Dougherty said. “It is certainly a priority of our office to ensure that body camera footage and all other evidence is properly maintained and available to defendants and our prosecutors.”

Eason’s attorney, Jeffrey S. Gard, said he was pleased the Court of Appeals will apparently be on alert for patterns within law enforcement agencies of failing to preserve evidence. Defendants have a burden under existing caselaw to show the evidence destroyed by the government was favorable to them, was unique in comparison to other evidence and was destroyed in bad faith.

“Judge Lipinsky brought to light the conundrum faced by all defense attorneys where evidence has been destroyed. How can we know whether it is exculpatory or not if we’ve never seen it?” Gard said. “How can the prosecution say it is not exculpatory if they have never seen it?”

Prosecutors charged Eason with two counts of assault and two counts of menacing when he reportedly grabbed a teenage boy and threatened him with a dowel before the boy’s brother intervened. Deputy Wesley Kugel responded and spoke to the two brothers.

Three months later, in October 2020, the defense requested all written statements and audio or video recordings in the case. Deputy District Attorney Erica Baasten informed Eason that Kugel’s body-worn camera video was “not retained due to some issue.” Kugel confirmed that he remembered having the video at the time of Eason’s arrest, but “I’m not sure why it didn’t get saved to the cloud.”

Although Eason moved to dismiss the case, the trial court judge denied the request.

During the first day of Eason’s trial in June 2021, it further came to light that the two victims had given written statements to police, which had not been unearthed as evidence. The Colorado Attorney General’s Office acknowledged on appeal that this “surprised both parties.” While the failure to turn over evidence was a violation of Colorado’s criminal procedural rules, Christopher J. Munch, the judge presiding over the case, again declined to dismiss it.

Munch did, however, throw out one of the menacing charges against Eason and offered to instruct the jury that the government had committed a mistake. Jurors ended up convicting Eason on the remaining menacing count alone.

The three-judge panel reviewing Eason’s appeal heard arguments from Gard that, although he had no idea if the missing video of the two witnesses would have produced evidence favorable to his client, Kugel’s written summary of the interaction was not a substitute.

“I‘ve practiced criminal defense for 25 years. I’ve never seen a police officer write down lots of wonderful, favorable things that would not support a charge against the defendant,” said Gard.

The attorney general’s office, which argued in favor of upholding Eason’s conviction on appeal, maintained that the defense had failed to show that the deleted footage was apparently exculpatory and was destroyed in bad faith. Lipinsky demanded to know why the court should accept that explanation when there was no indication of what the missing video contained.

“If we affirm, aren’t we sending the message to law enforcement that officers can destroy or not preserve these types of videos with impunity?” he asked. “Nobody will know whether they were or weren’t exculpatory. … They just disappear and then the law enforcement officer writes a summary that supports the prosecution.”

To date, constitutional due process violations for the government’s failure to preserve evidence have incorporated the requirement for defendants to show bad faith. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1988 decision of Arizona v. Youngblood confirmed that police negligence would not suffice, although four members of the Court disagreed with the bad-faith standard.

The Constitution requires “a fair trial, not merely a ‘good faith’ try at a fair trial,” wrote Justice Harry A. Blackmun in dissent.

Applying that precedent, the Court of Appeals panel upheld Eason’s conviction, concluding that the deletion of the video was an inadvertent error. Even the two other cases Gard mentioned, where Boulder prosecutors failed to request video evidence before the sheriff’s office destroyed it, did not amount to bad faith.

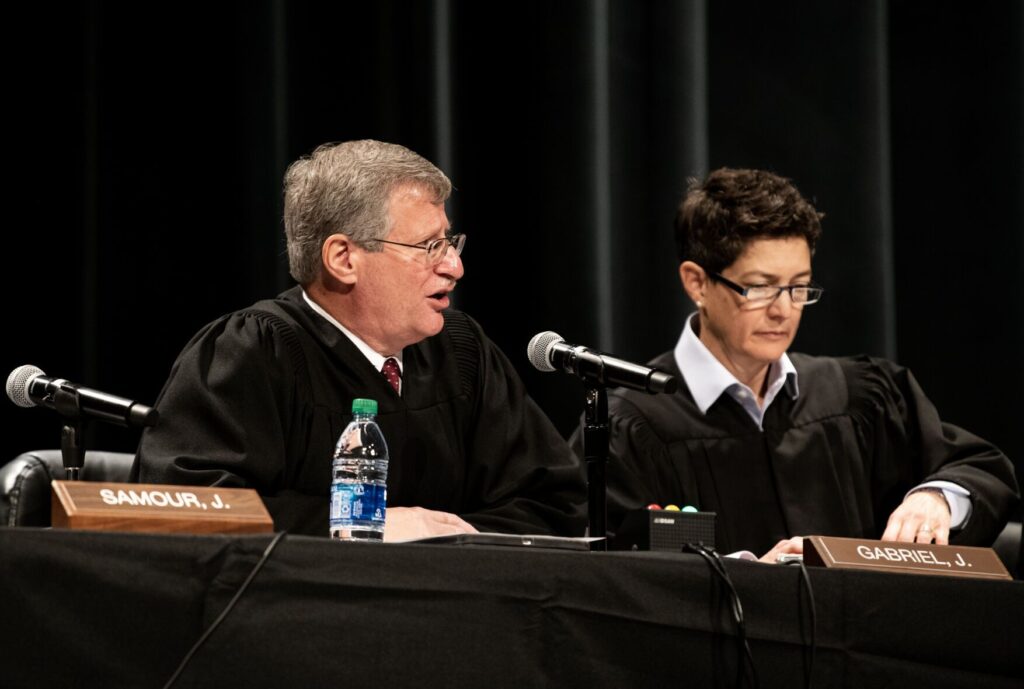

“We don’t mean to suggest that these incidents are – singularly or collectively – trivial. They aren’t,” added Judge Jerry N. Jones, writing for himself and Judge Christina F. Gomez.

In his concurrence, Lipinsky agreed with the outcome in Eason’s case. Because the circumstances surrounding the deletion of the two other videos were unclear, he indicated he could not conclude whether a pattern of retention violations was unconstitutional.

Nevertheless, Lipinsky did not believe it should matter whether an officer destroys evidence in bad faith or if an agency simply adopts a “lackadaisical” approach to retaining evidence.

“I would hold that the repeated destruction of potentially exculpatory evidence as a consequence of this type of careless approach to document retention violates a defendant’s due process rights,” he wrote.

Lipinsky explained he was unaware of a single appeal in Colorado where a court had agreed officers destroyed evidence in bad faith. He viewed that as a sign of the practical difficulty in proving someone acted in bad faith, adding that it “would be naïve to assume it has never occurred.”

A spokesperson for the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office said in response to the decision that the agency updated its evidence storage policy in September and was committed to following best practices. The spokesperson added that the rollout of body-worn cameras began in 2017 and would likely be complete this summer.

Mary Claire Mulligan, a defense attorney in Boulder, believed Lipinsky’s concurrence was an indication that the Court of Appeals is ready to consider whether the government violated a defendant’s due process rights if there is a documented pattern of evidentiary violations.

“This is great because the defense bar has been arguing for years that law enforcement gets away with bad behavior because of the high standard required for us to prove bad faith,” she said.

The Court of Appeals panel also rejected Eason’s other claim on appeal that the trial court was wrong to declare a COVID-19-related mistrial in March 2021 and postpone his trial. Eason claimed the delay was a “docket management strategy,” but the panel viewed it as reasonable given the public health concerns of the pandemic.

The case is People v. Eason.