District attorneys offer contrasting takes on new fentanyl law’s felony charge

District attorneys are offering divergent interpretations of the compromise that finally broke the gridlock and facilitated passage of the legislative response to Colorado’s fentanyl crisis, with some insisting the new language burdens prosecutors while others maintaining it does the contrary.

At issue is an amendment to House Bill 1326 that says a person caught with 1 to 4 grams of fentanyl may argue that he or she “had a reasonable, but mistaken, belief” that the drug “did not contain any quantity of fentanyl” or a similar synthetic opioid. If a jury agrees, then the offense becomes a Level 1 drug misdemeanor, instead of a felony. Under the amendment, that claim will have to be submitted as an “interrogatory” to either a judge or jury.

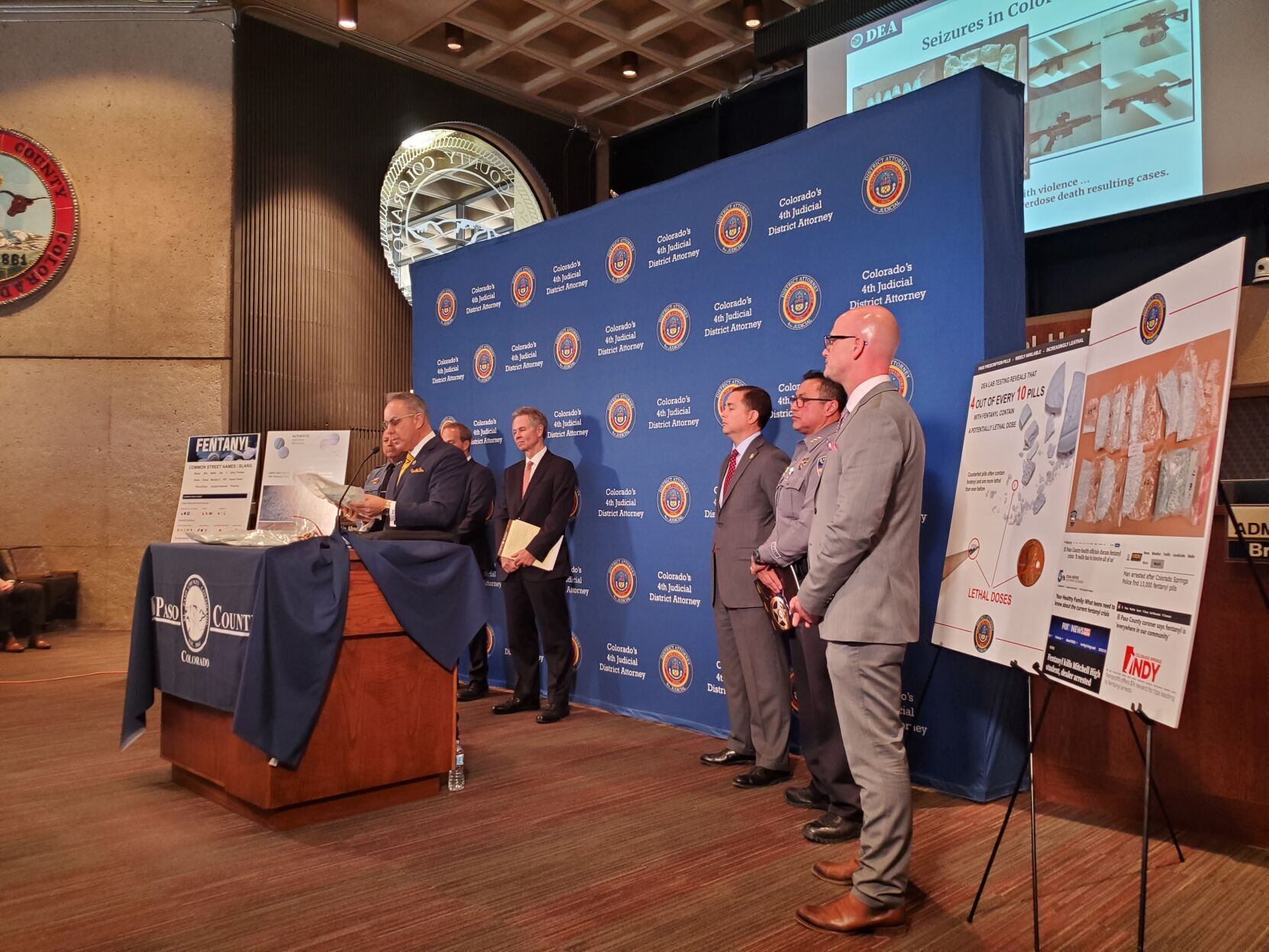

In a statement, Michael Allen, the district attorney for the 4th Judicial District in El Paso and Teller counties, said the bill “provides protection to low-level drug dealers and users who claim they did not know they were in possession of fentanyl.”

“Possessing 1-4 grams of fentanyl will now be harder to prosecute than any other illicit drug, despite fentanyl being the deadliest drug on our streets today,” he added.

John Kellner, the district attorney for the 18th Judicial District, expressed a similar view.

“Prosecution would have to prove they knew that the chemical compound had, in fact, fentanyl,” said Kellner, who represents Arapahoe, Douglas, Elbert and Lincoln counties. He also argued that the bill incorporates a higher standard than is applied on meth, cocaine and other drugs.

But Michael Dougherty, Boulder County’s district attorney who argued the bill gives the law enforcement community the tools it needs to confront fentanyl, said the burden, in fact, lies with defendants, who must show at trial “they truly didn’t know it was fentanyl.”

He said the amendment itself supports that view: The language says it only lowers the offense level “when a defendant shows supporting evidence to establish that he or she made a reasonable mistake of fact and did not know that the controlled substance he or she possessed” had fentanyl in it.

“The exact language … clearly reflects that the burden is on the defendant,” Dougherty told Colorado Politics. “The felony arrest and felony prosecution for possession of fentanyl is in the bill. The jury would then decide whether to convict on the felony or, if the defendant provides supporting evidence, the misdemeanor.”

Although some described the ability of defendants to show a reasonable mistake as an “affirmative defense,” such a maneuver requires the accused to admit to the charged conduct but provide justification for it. For example, Colorado law allows for the use of physical force in self-defense, including deadly force. If a judge determines that a jury can hear a self-defense instruction, jurors can acquit if they decide a defendant met all of the components for lawful use of force.

However, if the prosecution disproves beyond a reasonable doubt any piece of the affirmative defense – for example, that the defendant was the initial aggressor or provoked an attack – that would nullify it and result in conviction.

In contrast, defendants under HB 1326 would still be convicted, albeit of a lesser offense, if they could point to evidence showing they lacked knowledge that they possessed fentanyl.

Tristan Gorman, legislative policy coordinator for the Colorado Criminal Defense Bar, raised the same point.

“It is not an affirmative defense,” Gorman said. “It is a feature of an affirmative defense that the defendant has to admit they committed the defense charged. But then they say it was justified because of X.”

Under HB 1326, she explained, a defendant “does not have to put up any evidence like with an affirmative defense. They could rely on evidence presented by the prosecution and just argue in closing argument that was evidence that establishes the defendant made a reasonable mistake of fact.”

Ultimately, Gorman, said that language will only affect a small number of defendants because the vast majority of cases will get resolved with plea bargaining.

Other prosecutors suggested the public will have to see how it ultimately plays out in the courts.

Brian Mason, the district attorney for the 17th Judicial District in Adams and Broomfield counties, called the bill a “huge step forward.” He said litigation under the new law is “going to tell us what the language means.”

“The way I read it is we will submit to the jury what we call an interrogatory,” he said. “And the jury will decide whether the defendant knew or made a mistake” about fentanyl’s presence in a drug.

Under that scenario, both the defense and prosecution can offer evidence to the jury to help the latter answer that question, Mason said.

Brionna Boatright, director of public affairs for the First Judicial District Attorney’s Office, which covers Jefferson and Gilpin counties, noted the possibility of prosecutors collaborating with the Colorado District Attorneys’ Council and the attorney general in interpreting the new law.

“As with all new laws, we plan to consult with other district attorney offices and expect to receive guidance from CDAC and the AG’s office going forward,” Boatright said.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com