Here’s what the legislature’s newly passed fentanyl legislation will do

Two months after it was introduced, House Bill 1326 – officially dubbed the Fentanyl Accountability And Prevention Act – squeaked out of the Legislature at the last minute Wednesday night.

It wound through two House and two Senate committees and a conference committee, was the subject of scores of amendments and was one of the most controversial bills of the session.

Colorado district attorneys split on what fentanyl compromise means

Now the bill, spanning more than 90 pages and allocating tens of millions of dollars, awaits Gov. Jared Polis’ signature. Much of the debate around it from the public involved a relatively short, but deeply consequential, provision about simple possession of fentanyl. But what else does the bill bo?

Criminal penalties

To the frustration of bill sponsors and others involved in the process, the vast majority of public testimony and legislative debate centered on the criminal penalties in the bill. The most contentious of those is how the bill addresses possession.

The bill makes it a felony to possess more than 1 gram of any substance containing fentanyl, carfentanil, benzimidazole opiate or analogs of those substances. The criminal penalty increase above 4 grams. Under 1 gram, possession of those substances is a misdemeanor. The bill allows defendants charge with that new felony to argue to a judge or jury that they didn’t know they possessed fentanyl (the drug has contaminated much of the drug supply, and users of other substances – meth, cocaine, heroin, pills – often don’t know they’re taking or buying fentanyl). If they successfully do so, an ensuing conviction would be a misdemeanor instead of a felony.

The bill sets sentencing parameters for people convicted under this new felony charge, which include a fentanyl education program and may include a treatment program. It also allows people convicted under this charge to apply to have their records sealed earlier than would be possible under other drug felonies.

Colorado Springs mayor urges Polis to veto fentanyl bill and convene special session

Beyond possession, the bill also increases penalties for distributing any amount of a substance containing fentanyl, carfentanil or benzimidazole opiate. It automatically makes it a high-level drug felony for anyone convicted of dealing substance containing those drugs that led to death. It would similarly hit someone with a that same conviction level if that person brought the substance into Colorado or had certain equipment, like a pill press.

It’s a level-two drug felony, which carries heavier penalties than a simple possession felony conviction, if the substance is more than 60% fentanyl, carfentanil or benzimidazole opiate. But that only kicks into place when law enforcement confirm they have the ability to test substances to that level of specificity.

EDITORIAL: Fentanyl bill may do more harm than good

The bill would give immunity from the resulting-in-death provision to someone who calls 911, stays on scene and cooperates with law enforcement in the event of an overdose. Prosecutors are required to track and file reports on prosecutions and non-prosecutions related to this section for three years.

Treatment in correctional settings

The bill includes a number of provisions related to substance-use assessments and treatment in correctional facilities. The bill requires community correctional facilities to develop protocols for withdrawal management, ensure medically appropriate care and provide a referral if needed, including for medical detox. By July 1, 2023, they’re required to begin providing medication-assisted treatment – considered the gold-standard way to treat opioid-use disorders. If they can’t offer MAT, the programs must help inmates assess MAT providers in the community, and the program has to submit a report to the state describing the barriers preventing it from providing MAT itself.

Anyone convicted of the new possession felony must be assessed for history of substance use; their amenability to treatment; and the level of treatment they would need. Community corrections or residential treatment may also be ordered as part of probation, and nonresidential treatment may also be ordered if residential treatment isn’t available.

By July 1, 2023, all correctional facilities must provide MAT and other appropriate services to qualified inmates. That’s a significant change: Jails and prisons haven’t been required to offer that. The bill allocates $3 million and encourages jails to use opioid settlement money to support the programs going forward.

Those inmates who received MAT, should’ve received MAT or have a history substance use are to be be given an antagonist, like naloxone, upon release. Jails are also required to give medication for opioid-use disorders and a referral for MAT treatment in the community, and they must help coordinate newly released inmates’ continued care.

Monitoring

The bill requires a number of studies and monitoring reports, often about its own impacts. For instance, it requires tracking of cases involving distribution and resulting in death.

By Jan. 1, 2023, the bill requires managed service organizations to report on the supply and demand of nearby MAT providers; withdrawal management organizations; and the provision of recovery services at high schools and residences in the area.

The stat will be required to hire someone by Jan. 1, 2023, to study other impacts of the bill, including impact of possession changes, how often defendants were charged with felonies versus misdemeanors, whether substance-use treatment was ordered, and the race, gender and age of people charged. That report must be filed before the end of calendar year 2024 and published publicly by Jan. 31, 2025.

The Attorney General’s Office is required to study the use of the internet in selling and buying synthetic opioids. The state must also study the health effects of making fentanyl possession a felony to see, among other things, if the penalties increased or decreased fentanyl overdoses on those people charged with misdemeanors and felonies alongside those who weren’t charged.

First responders must report fatal and nonfatal overdoses for a mapping tool by Jan. 1, 2023.

The state Department of Public Health and Environment must get input on an overdose trend review committee to review overdoses in Colorado; identify causes and factors related to overdoses; develop evidence-based recommendations to prevent them. The report on establishing the committee must be filed by Sept. 1, 2023, and the committee itself has to be established a year later.

Naloxone and fentanyl test strips

Among its least controversial provisions, the measure seeks to bulk up the amount of naloxone and fentanyl test trips available to the public.

It allows prescribers to give naloxone to institutions of higher education; a library; community service organization; jails and correctional facilities; probation and pretrial service programs; mental health professionals; and local public health agencies. It also loosens restrictions on storage and record-keeping related to naloxone, removing a barrier for hospitals; it also requires Medicaid to reimburse hospitals that give naloxone to Medicaid patients.

It gives immunity to people distributing fentanyl test strips in good faith, and it allows schools to implement a policy to dole out test strips.

There’s also some serious money involved: $19.7 million to buy naloxone, plus $600,000 to buy test strips.

Education

The state health department would be required to stand up a statewide fentanyl education program beginning in the 2022-2023 fiscal year. That can involve TV, print and radio ads, and it requires five regional training sessions for youth development strategies, plus a website.

Harm reduction

The bill also expands who is eligible to receive harm-reduction grant funding from the state and for what purposes the grant money can be used, including for overdose prevention, general operating expenses, test strips and efforts to keep people out of jail or prison. It puts $6 million in the grant fund the 2022-23 fiscal year.

Crisis management and withdrawal care

By Jan. 1, 2023, managed service organizations would be required to provider short-term placement for crisis stabilization, withdrawal care, or MAT for people in need of immediate detox. The bill allocates $10 million for that purpose.

Investigations

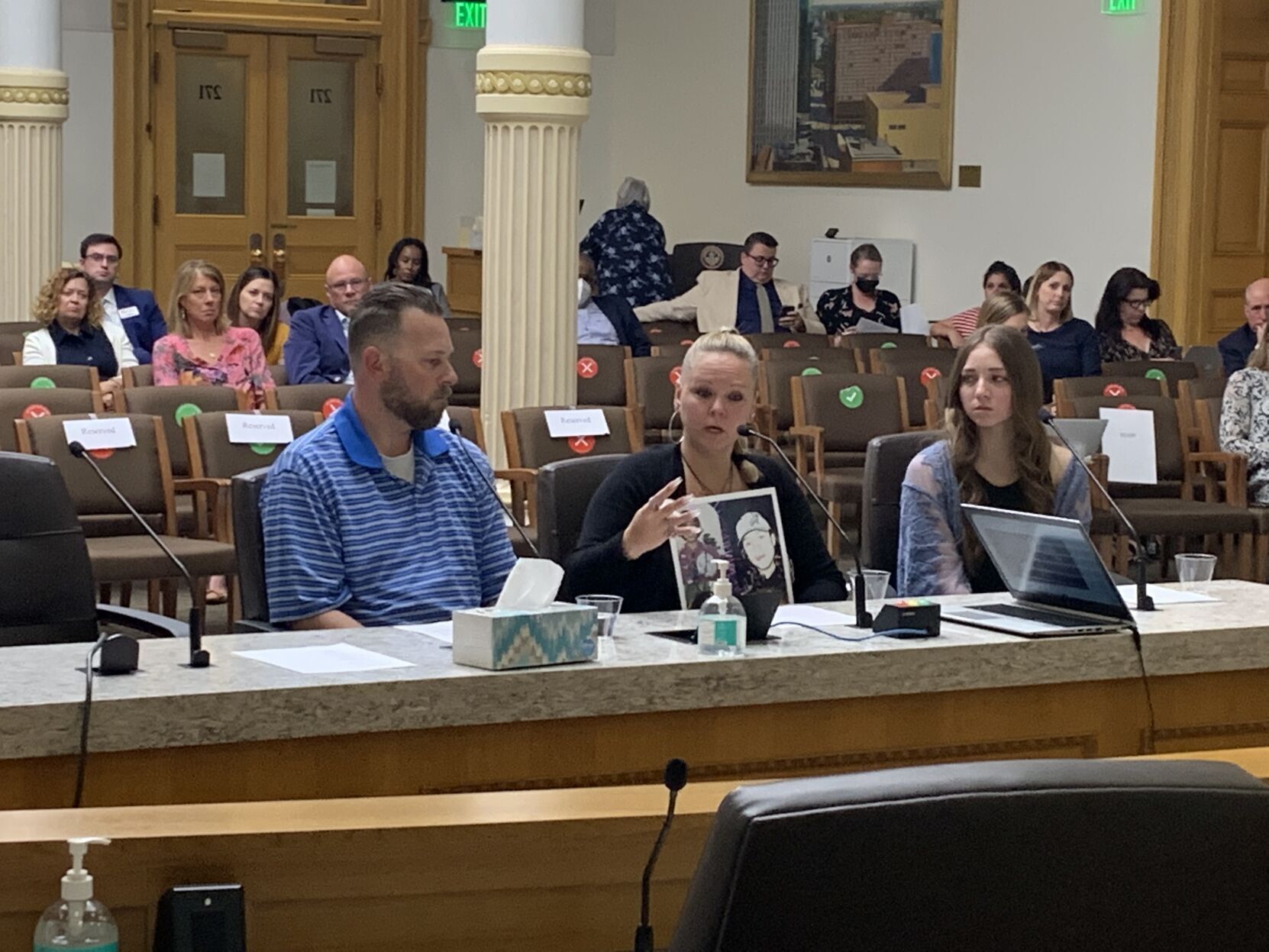

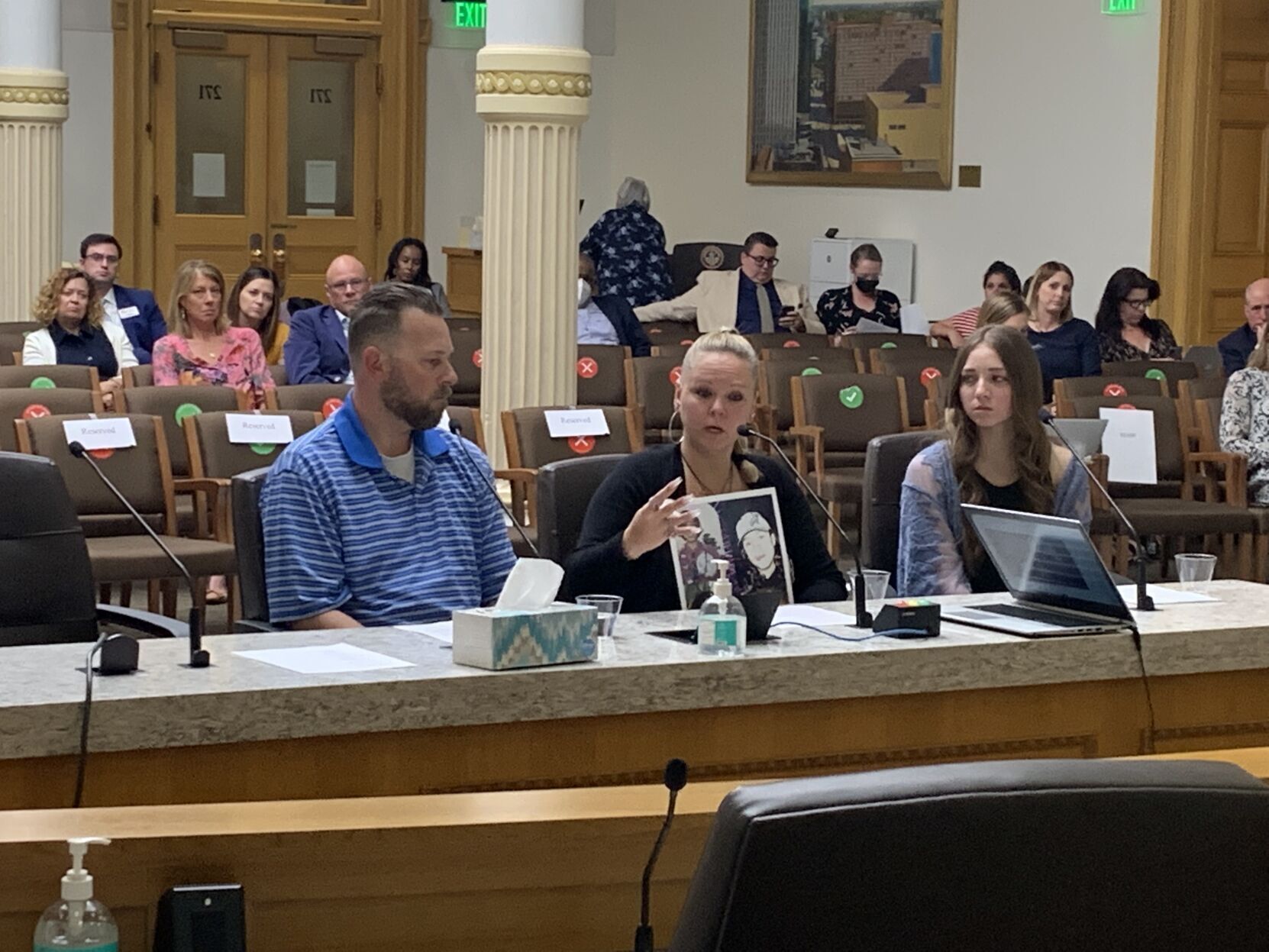

During public testimony on the bill, several families told lawmakers that they were dissatisfied with the criminal investigations that followed the overdose death of their loved one. The bill would create a grant program to give money to law enforcement agencies investigating deaths or serious injuries from synthetic opioids. That money could be used to investigate deaths, injuries or distribution networks. It could also be used to purchased relevant equipment or to analyze emerging trends.

Behavioral Health Administration

The bill directs the newly formed BHA to encourage all insurers to cover substance use treatment, and it would allow peace officers to seek involuntary substance-use commitments for certain people.