Colorado House approves bill that tightens penalties for low-level possession, distribution of fentanyl

The Colorado House of Representatives gave preliminary approval to a bill Friday evening to address the state’s growing fentanyl crisis following another hours-long debate that focused on whether possessing the substance in any amount or form should be a felony.

For now, the balance of Colorado’s House members said no.

After five hours of debate, legislators, who worked into the night, approved House Bill 1326, which, in its most current version, tightens criminal penalties for distributing any amount of the drug and for dealers whose pills kill someone and makes it a felony to possess anything more than 1 gram of it in any form. It also sets aside millions to pay for medicine to reverse overdoses and test substances for fentanyl, while establishing education programs and advocating for a key treatment protocol in incarceration settings.

The bill, which still needs the full House’s final vote, is a comprehensive but not final approach to addressing fentanyl, said House Speaker Alec Garnett of Denver and Rep. Mike Lynch, a Wellington Republican, who co-sponsored the legislation.

“There’s still work to be done,” Lynch said. “This is by no means the silver bullet, but I think for us to ignore the work that has gone into this would not do it justice. We’ve done what we think we can do.”

The House’s action came two days after Gov. Jared Polis told Colorado Public Radio that possession of any amount of the substance should be a felony, and he likened it to anthrax. Rep. Terri Carver, a Colorado Springs Republican, and others also emphasized fentanyl’s deadly nature, while other members, such as Rep. Leslie Herod, D-Denver, blasted what they described as efforts to incarcerate people with substance use disorders.

Policymakers noted the drug’s grim death toll in Colorado throughout the day. According to state data, nearly 900 Coloradans fatally overdosed after ingesting fentanyl – alone or in another substance – in 2021. Nationwide, more than 100,000 Americans died over a 12-month period ending in November, the majority of which from synthetic substances like fentanyl.

The issue of incarceration dominated Friday’s debate, while considerably less time was paid to the measure’s less controversial provisions, which include a statewide education campaign, millions of dollars for Naloxone and test strips, and increased emphasis on evidence-based treatment offerings in jails.

Garnett, the bill’s co-sponsor, has lamented that fact repeatedly in recent weeks as the bill began to make its way through the statehouse and the debate over possession eclipsed all else.

Fentanyl’s arrival, the result of a shifting drug supply and the effects of the pandemic, pits two forces against each other: One is the recent push to treat drug use and possession more as a health, not criminal, problem. The other arises from fentanyl’s unique nature: a powerful synthetic drug that’s replaced heroin for many people struggling with substance use and is added, often without the knowledge of the user, to other substances, such as meth and cocaine.

Carver, Polis, Attorney General Phil Weiser and others argue that fentanyl’s strength and its presence in other substances – with often lethal consequences – make it a unique threat that requires zero tolerance. Many in that camp also argue that incarceration for users is a way to keep them alive and get them treatment.

Herod, Reps. Jennifer Bacon and Mike Weissman, as well as various experts and advocates counter that fentanyl’s presence in other drugs is precisely why it simple possession cannot be made a felony. To “felonize” any amount of fentanyl, they argue, is to, de facto, “felonize” possessing any amount of any substance, since much of the drug supply has been contaminated with fentanyl.

At the same time, they say, zero-tolerance possession will incarcerate people knowingly using fentanyl because they are physiologically dependent upon it.

Carver made repeated attempts to tighten penalties for possession and distribution, with each one failing. She also tried unsuccessfully to end a clause in the bill that would end the 1 gram felony threshold in three years.

Speaking in favor of one of Carver’s efforts, Rep. Rod Bockenfeld, R-Watkins, said dealers are “indifferent” to the harm their drugs deliver.

“We keep worrying about drug user, getting them rehabilitated, passing off their illicit drug, knowing they can kill another person, and that’s okay?” he said. “I’ve listened to the tear-jerk, heartbreaking stories from parents who didn’t know their child was on drugs.”

Herod emphasized earlier in the debate that the bill already deals with dealers by increasing penalties for distributing any amount of the drug. She and others stressed that changing the possession laws to zero tolerance would incarcerate many users, of fentanyl and other substances, and would permanently affect their lives by designating them as felons.

Rep. Matt Soper, a Delta Republican, backed an effort to set a zero-tolerance approach but with a provision to turn the conviction into a misdemeanor for people who completed mandatory treatment. Rising in opposition, Rep. Shane Sandridge, a Colorado Springs Republican and former police officer, said incarceration “has been tried. Didn’t work.”

While praising law enforcement, he advocated that lawmakers should go to “experts for our answers that show clear data of what’s going on.”

“What’s the definition of doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result?” he said.

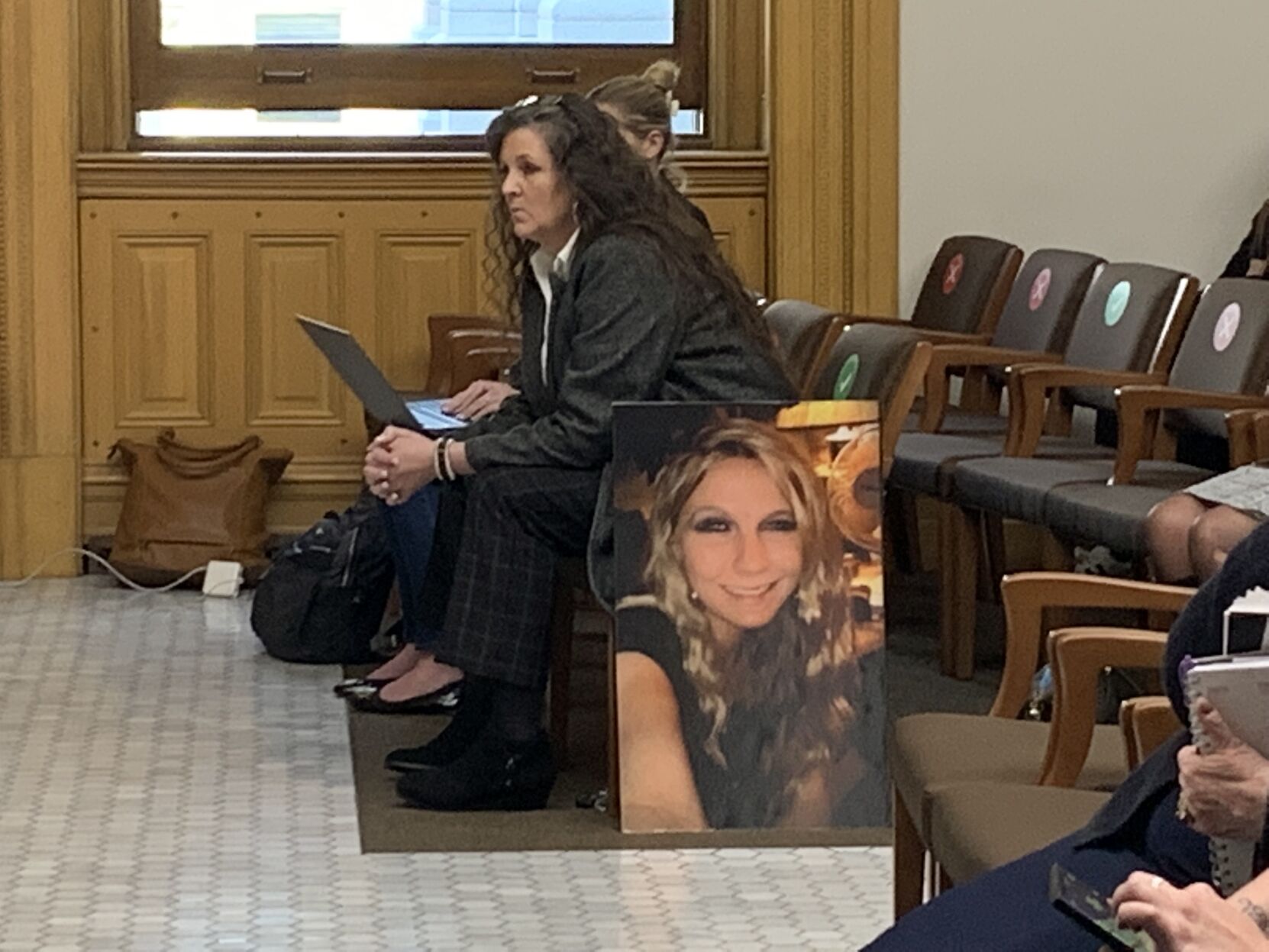

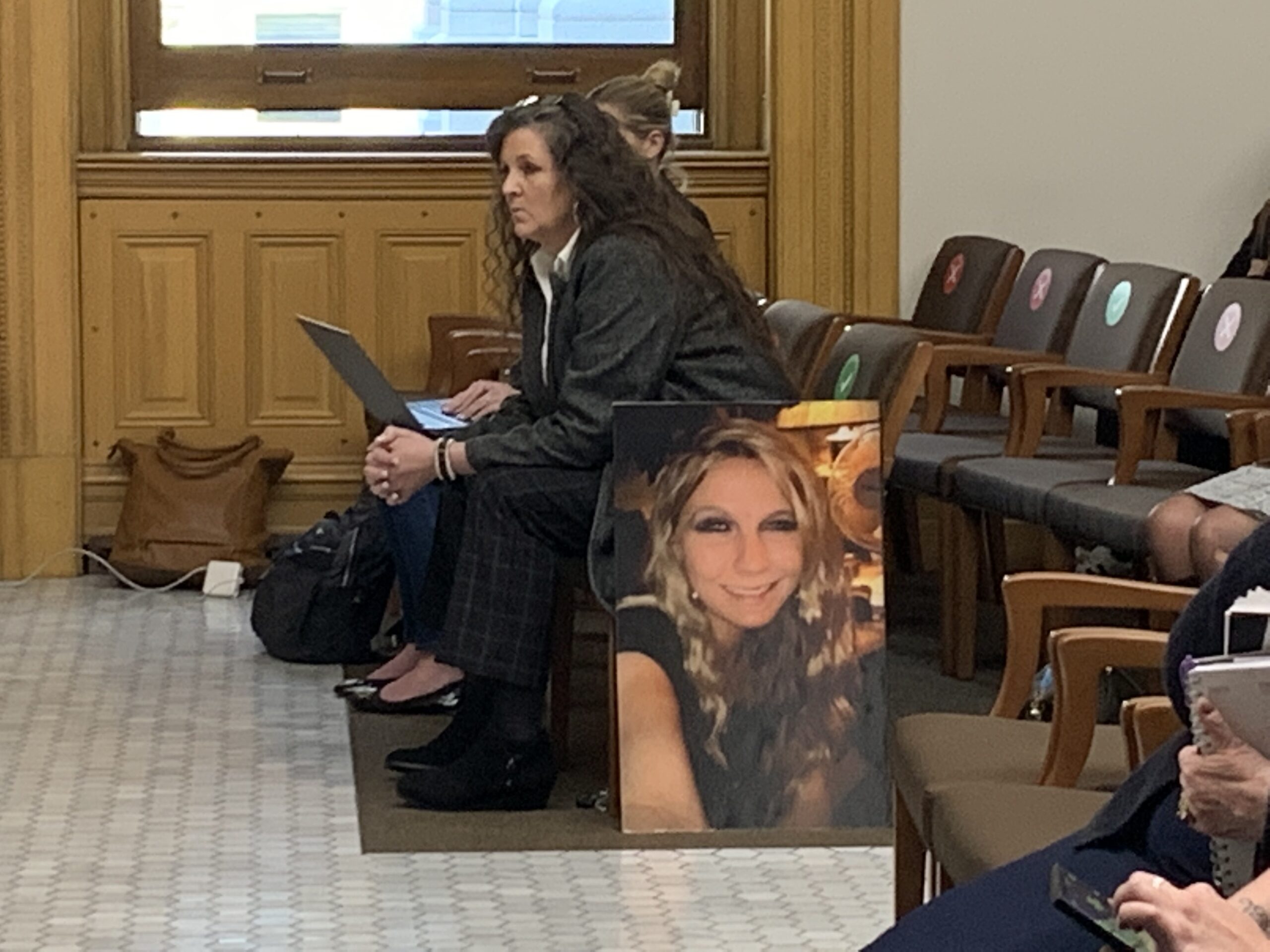

The bill was amended Friday to add an investigation grant program for law enforcement, addressing concerns raised by families that their loved ones died after taking fentanyl but their deaths were classified as overdoses rather than homicides. They had sought changes to require law enforcement to investigate those deaths.

HB 1326 now awaits a final vote in the House, which is likely to occur on Monday, and then it heads to the state Senate, where it will be sponsored by Sen. Brittany Pettersen, D-Lakewood, an long-time advocate for opioid treatment, and Sen. John Cooke, R-Greeley, the former sheriff of Weld County.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com