Colorado’s 2022 economic forecast shines bright, with warnings

Colorado should recover this year all the jobs it lost during the pandemic, and many industries are poised to return to pre-pandemic levels of business, according to panelists at the South Metro Denver Chamber of Commerce economic forecast breakfast Friday.

“Most economic activity is getting back, or will be back in 2022 to where it was before the pandemic,” said Henry Sobanet, senior vice chancellor of Administration and Government Relations/chief financial officer of the Colorado State University System.

“Four states – Utah, Texas, Idaho, Arizona – have recovered, or are past pre-pandemic employment levels. That’s, in part, driven by significant in-migration from higher-cost states.”

About 500 business representatives and government officials attended the event at the Marriott South at Park Meadows, moderated by The Denver Gazette.

State recovery lags behind some neighbors

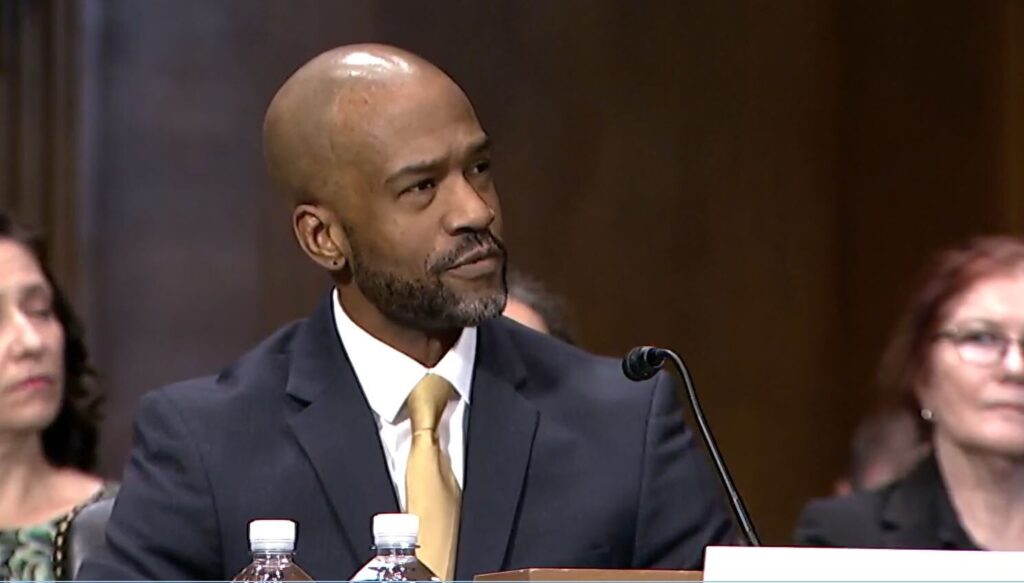

The other panelists were Colorado State Demographer Elizabeth Garner and Tuhin Halder, vice president of finance and chief financial officer of Comcast’s Mountain West Region – who talked about supply chain issues.

The panelists warned there could be speedbumps to full recovery, including inflation, workforce availability and morale, supply disruptions, housing affordability and pandemic uncertainty.

“It wasn’t the same pandemic for everybody, and it’s not the same recovery for everybody,” Sobonet said. “Policy and business planning of all kinds needs to take this into account.”

“The big question for 2022 is will the economy open and will we go back to the services side of the business, or will we stay home and continue to buy goods online?” said Halder.

“We need to be aware that there’s still a lot of risk to this forecast,” said Garner.

Garner used the 2020 U.S. Census data for Colorado to show the state’s in-migration is not as rampant as everyone seems to believe.

“If you only stared this picture (slide showing population growth), looking at 2010 forward, you would definitely think we’re in a population boom,” Garner said. “But if you go back to 1990, you’d say, ‘Oh, we’re about average.’ That’s why I’m going to encourage all of you to look at your narrative. Think about what you’re saying and what you’re hearing in terms of time perspective and in terms of (population) growth.”

Another international company tabs Denver for U.S. headquarters

Colorado reached 5.77 million residents, according to the 2020 Census data. It grew by 744,500 residents, or 14.8%. Ninety-five percent of that growth occurred on the I-25 corridor, as opposed to the 2000-2010 figures that showed 78% of the growth occurred on the Front Range, she said.

The growth rate peaked in 2015, and “every consecutive year after that has seen a slowdown,” said Garner. There were actually more births (648,000) in that decade than net migration (445,000).

“So when you hear people are flocking here, you should respond ‘say what?’,” she said.

Garner said businesses need to worry about losing Colorado’s youth.

“We’re getting a full-court press from states to attract our kids out,” said Garner. “They want butts in seats and understand the correlation with that and economic development. If you get that kid in a college seat, you’ve got a really good chance of also including them into your economy. So we need to be concerned about that.

“I’ve heard folks say ‘I’m totally done with people coming here.’ But how can we hate people coming and love jobs growth? That’s the job of all you guys (business representatives in the audience) to help message. The narrative out there needs to be that if you’re going to be pro-job growth, you also need people to fill those positions.”

Sobanet said he expects the “Great Resignation” to continue, as households have more confidence the stock market, increased housing value and increased savings levels.

The “quit rate” from 2000 to present is the highest it’s been, he said according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Year in review: Economic recovery top business story of 2021

“This is absolutely brutal for an employer when an good employee leaves with the transition costs, the cost to hire a replacement, the time it takes in lost productivity – but that’s the market economy,” said Sobonet. “That’s capitalism.”

On supply chain issues, Halder said it’s showed up in the strangest places: Like Starbucks running out of sleeves and having to double-cup orders or people having a hard time getting windshields replaced because manufacturers have turned to making glass vaccine bottles.

“It’s a concoction of craziness that has led us to where we are, and we are all paying for it,” said Halder. “Folks not being in the workplace is causing bottlenecks in our ports and airports.”

Denver Gazette Business Reporter Dennis Huspeni served as the moderator for Friday’s event.