City Council public safety working group hears from police chief

Denver’s police chief believes the department’s new strategy for reducing violent crime by focusing on the areas where incidents are most concentrated has seen some success, but he said the police department is prepared to adjust its targeted efforts as crime shifts to other areas.

The Denver City Council working group convened to consider 112 recommendations made by a community-based public safety reform task force in the spring began its meeting Monday with a presentation from Police Chief Paul Pazen about a policing strategy the department announced in late May to target violent crime.

The agency has termed it “collaborative policing” because it’s designed to work with other city departments and community organizations to connect people with social services and promote economic development to address root causes of crime, such as poverty.

“The biggest part of it is working with our community helping to engage with folks, building on those tenets of community policing in order to fill that void when we disrupt that [criminal] network. If we take a drug dealer off the street, we want to fill that space with community, and not have that vacuum filled by another drug dealer,” Pazen said.

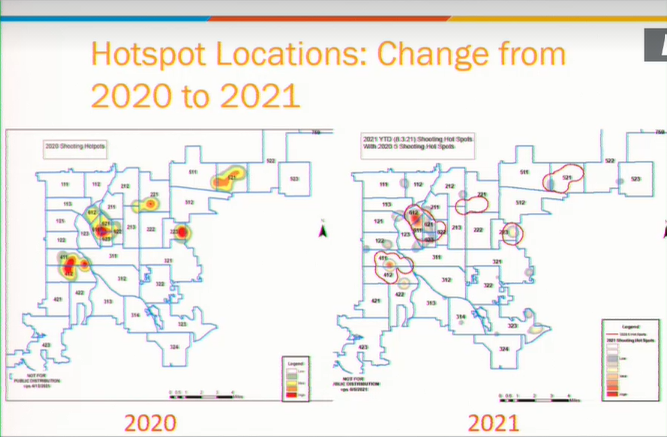

The police department has said that in 2020, 49% of shootings and 26% of homicides happened in five “hot spots” they identified centered on intersections across Denver, even though the areas made up only 1.56% of Denver’s land mass, excluding DIA.

Specific areas require tailored strategies based on the types of violent crimes most prevalent, such as drug or gang-related incidents, he said. But Pazen added instances of people with felony convictions who have firearms illegally are an issue across Denver.

Among solved homicides last year, he said, about 58% of them involved suspects with previous violent felony convictions. Twenty-five percent of them were on some kind of court-mandated supervision, such as pretrial release, parole or probation. In 2021, eleven of 28 solved homicides – cases in which police have made an arrest — involved suspects on supervision.

Pazen referred to people with prior violent felony convictions who are barred from owning guns as “hot people.”

“We need to work more collectively as a criminal justice system in order to prevent the harm that is taking place in our community,” he said.

Pazen said according to data collected through Aug. 3, the police department has made some progress reducing incidents in the hot spots. One of the spots that’s mostly located in the Northeast Park Hill neighborhood, at Holly Street and Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard, has not had any shootings this year, he said.

Particular efforts tailored to that area include outreach to youth leaders in the area, he said.

District 9 Councilmember Candi CdeBaca pushed back on Pazen’s use of that metric as an indicator the police department’s collaborative policing strategy is working, since the city announced its launch in late May.

“So for five months [in 2021] we didn’t technically have the program, but you’re attributing the lack of shootings at MLK and Holly that technically didn’t exist until May?” she said.

CdeBaca also asked Pazen to explain how the strategy differs from broken-windows policing, a strategy implemented in Denver in the mid-2000s based on theories that signs of disorder in a community – analogized to a broken window in an abandoned building that goes unrepaired – can encourage more serious crimes, and that cracking down on low-level crimes can help prevent bigger ones.

Pazen said he believes the police department’s collaborative strategy is different from broken-windows policing because it focuses on the most serious crimes, violent offenders and relationship building in communities to address root causes of crime rather than using arrests and citations for low-level crimes as a strategy.

His exchange with CdeBaca got tense when she said his statement about reduced shootings this year at Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard and Holly Street seems to suggest the department’s increased policing in the area – which CdeBaca termed over-policing – would not be necessary anymore.

“Those are your words. Those aren’t my words. Our focus is not on over-policing; our focus is on keeping communities safe and connecting people with the resources that they need,” Pazen said.

District 2 Councilmember Kevin Flynn asked whether there is a possibility that crime has just been shifted around between neighborhoods as police focus resources on particular areas.

Pazen said that has created challenges as police figure out factors driving crime and target resources in response. As an example, he explained that in 2020, police saw violent incidents resulting from personal disputes that escalated. This year, he said, drug-related violent incidents have risen. And as police have targeted efforts to crack down on drug-related incidents, activity has shifted from the Civic Center area to the Ballpark neighborhood.

“This is a concern that we monitor across the entire city. If there are flare-ups in certain areas, then we shift our resources,” Pazen said.