Biden executive order brings hope and memories to one Liberian immigrant

Among the lesser publicized executive orders signed by President Joe Biden on his first day in office: one that would reinstate a delay on enforced deportations for Liberian immigrants.

The order is expected to impact about 4,000 Liberians living and working in the United States.

The order got little attention, save for places like Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Rhode Island and Aurora, Colo., all which have large Liberian immigrant communities.

But it caught the attention of one of Colorado’s first-year lawmakers, Rep. Naquetta Ricks, D-Aurora.

The order’s history goes back decades.

In 1991, the United States began providing a safe haven for Liberians who fled their country as a result of armed conflict and widespread civil strife.

Those immigrants were granted temporary protected status. Once the civil war ended in 2003, Liberian immigrants continued to have that status until 2007. It’s been extended by every president since then. However, President Trump decided in March 2018 it was no longer needed and ordered it to end in March 2019, putting those Liberians at risk for deportation. Trump quietly extended the order to March 2020.

In the meantime, Congress, through its 2019 National Defense Authorization Act, took action on its own. In December, 2019, Congress granted Liberians who had been in the United States since November of 2014 eligibility to obtain lawful permanent resident status (green cards), with an application deadline of Dec. 20, 2020.

That gave Liberian immigrants a year to finalize their status.

Biden’s executive order extends the temporary protected status, including for employment, through June 30, 2022, and in the order encouraged Liberians to apply for permanent status.

Ricks is more than a little interested in what becomes of those Liberian immigrants. She once was one.

The civil strife in Liberia dates back at least four decades, Ricks recently told Colorado Politics. She remembers.

Ricks was born in Liberia in 1967. Up until 1980, she lived an upper-middle class life in a suburb outside of the capital city of Monrovia.

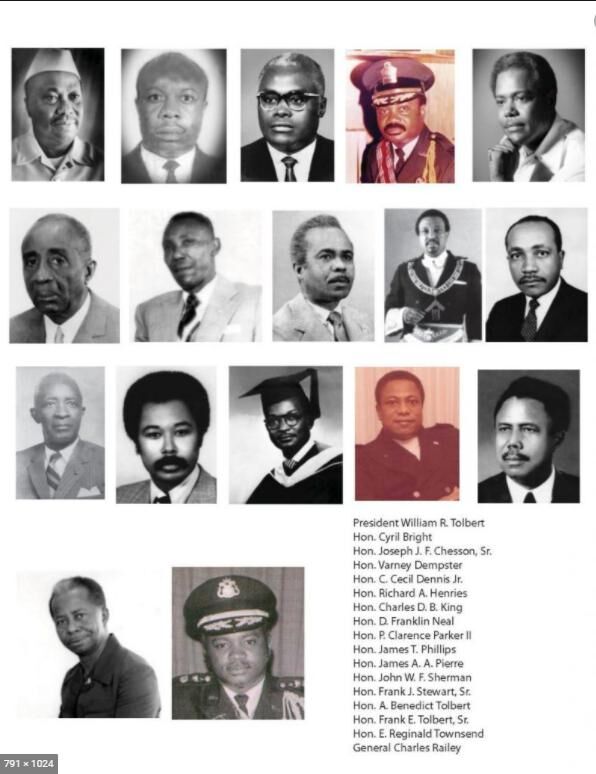

That all changed in April, 1980, when a military coup d’etat led by Samuel Doe overthrew the democratically-elected government and murdered the president, William Tolbert. Soldiers came to her home during the coup and interrogated her mother, Mariam Eudora Ash, whose fiancé, Cyril Bright, was the minister of agriculture as well as minister of planning and economic affairs. Ash was part of the Mono River Union, a coordinator of a joint venture between Liberia and Sierra Leone. She was a high-profile person, Ricks said, and a very outgoing woman.

The soldiers found Bright, dragged him out and threw him into a truck and took him away. According to one account, 13 cabinet members, including Bright, were “walked publicly around Monrovia in the nude and then summarily executed by a firing squad on the beach.” (The nation recently held a 40-year memorial service for the 13 murdered ministers). Doe was overthrown in 1990 and was tortured and executed publicly a year later.

Ricks remembers fleeing their home. Her last memory of Liberia is that day, the day soldiers pointed guns at her mother. “After that, we ran. Everything was a blur. We grabbed clothing” and by June were headed to the United States as refugees seeking political asylum.

Both her parents were educated in the United States and had family in Colorado, so that’s where they headed. “We left our friends, we left everything.” Ricks said.

Ash took whatever jobs she could find to support her daughters.

Their request for political asylum was denied. “You had to tell your story and how you had been victimized,” Ricks said. Her mom could not prove what had happened to them.

But by 1988, an immigration reform bill had been passed by Congress and that opened the door for citizenship, which Ricks and her family obtained that year. Just two years later, Ash died of breast cancer.

Ricks remembers her first day in high school, at Aurora Central, walking in like a “deer in the headlights.” Everyone wanted to know where she was from because of her accent. “They didn’t know I had come through trauma,” a story that she said she hasn’t told until recently.

Ricks still travels to Liberia from time to time, mostly recently in 2018. She works with the country’s nonprofit surfing association – the west African coastal nation has some of the best surfing waters in the world – and on literacy issues, given that two-thirds of Liberian women cannot read. She also founded, in 2015, the African Chamber of Commerce in Colorado to encourage economic growth, collaboration and investments in Colorado’s African immigrant communities.

The country’s political situation, while no longer in chaos, still has problems, she said. “They’re not doing the right things for people and there’s still a lot of scandal.”

Aurora is home to 3,000 to 4,000 Liberians, Ricks estimated, a robust community with a couple of churches, including one headed by a Liberian pastor. Colorado is home to some 49,000 African immigrants, she said.

They work in a variety of industries, but health care is a major one, she explained.

On being elected: Ricks is one of two Liberian-Americans who fled the civil war to be elected to state government in 2020. The other is Nathan Biah, who was elected to Rhode Island’s state House.

Ricks says she might have been the first Liberian-American elected in Colorado, but vows she won’t be the last. “The door is opening. Immigrants are running” for elected office. “People who have lived experiences like myself, we’ve cracked the glass ceiling” with more who will be elected to school boards, legislatures and Congress.

“Representation matters,” Ricks added. “It’s important for little girls to see someone with an accent” and bring the plight of everyone, including immigrants, to the state Capitol.

Ricks watched the Jan. 6 insurrection with shock. Forty years after fleeing from a military coup, she said she was shocked to see such a thing happen in what she called the bedrock of democracy.

She intends to make part of her agenda restoring faith in government, and to make sure all voices are heard.